Unsatisfied with the direction that the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) was heading toward with respect to its outdated Rationalist views on urbanism and the bureaucratic nature of the group, a small team of architects known as Team X, or Team 10, sought to, and succeeded in, restructuring CIAM. 1

The primary constituents of Team X were architects Jaap Bakema, Aldo van Eyck, Alison and Peter Smithson, Georges Candilis. These were all some of the younger members of CIAM, and more importantly, they were part of the CIAM X Committee, a group dedicated to planning the upcoming CIAM meeting. 2 In becoming the council for CIAM X, the group, now officially known as Team X, were able to push the conference toward their own agenda. Their reorganization of CIAM first came to fruition at the end of the CIAM X conference in Dubrovnik in 1956, with the official CIAM Council resigning and leaving CIAM in the hands of the a reorganization committee largely consisting of Team X members. 3 In 1959, there was a meeting to discuss the reorganization of CIAM, but, somewhat ironically, this was the last meeting that would bear the title of CIAM, and hence marked its death. 4

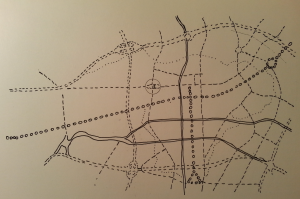

Some of the founders and most prominent architects of the time, including Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, sent a letter to Team X expressing their disapproval of the end of CIAM and the direction the group was heading. In response, Team X outlined their goals, providing a manifesto of sorts, which explained that they were seeking to build a “working-together-technique” to address the issues they found rampant throughout rationalist urbanism. 5 Primarily, Team X was concerned with designing and reforming cities so that they were “comprehensible”, or clearly organized. 6 By specifically addressing the issues now prevalent in the motor age such as a need for motorways, and embracing the possibilities that this age brought, such as the potential for larger, more diverse and functionally-situated areas, the urban landscape would become more livable. 7 Figures 1 and 2 below help to exemplify this issue. In their plan for Berlin, the Smithons and Sigmon sought to have pedestrian walkways (figure 1) over streets and connecting through buildings to provide a free-flowing pedestrian traffic in unison with, but apart from, the motor traffic beneath. Even with this, Berlin needed to be connected via motorways, so a complex chain of streets and highways was envisioned by the Smithsons and Sigmon to achieve this, pictured in figure 2.

Designed by: A. &. P Smithson and Sigmon in 1958

Designed by: A. & P. Smithson and Sigmond in 1958

Ultimately, Team 10 would itself dissolve due to internal disagreements regarding interpretations and ideologies of urbanism present from its inception. 8 This led to the foundation of New Brutalism via the Smithsons and Structuralism via Bakema and van Eyck. As such, during a time of architectural stagnation, Team X broke down one of the main forces causing this, CIAM, and slowly paved the way for new forms to take their hold in modern architecture.

-SR

Figure 1: Alison Smithson, Pedestrian net structuring the central area of Berlin. Taken from: Alison Smithson, “Team 10 Primer”, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1968), 50.

Figure 2: Alison Smithson, Berlin Plan. Taken from: Alison Smithson, “Team 10 Primer”, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1968), 51.

Notes:

- Team 10, “Team 10: 1953 – 1981: In Search of a Utopia of the Present” (Rotterdam, NAi Publishers, 2005), 11 – 13 ↩

- Ibid, 43 – 45 ↩

- Ibid, 52 – 53 ↩

- Ibid, 61 – 63 ↩

- Ibid, 92 ↩

- Alison Smithson, “Team 10 Primer”, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1968) 48 – 52 ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Team 10, “In Search of a Utopia”, 43 – 45 ↩