by Elise Wachspress

One of the more frustrating terms in the medical jargon is “idiopathic.” The word means “arising spontaneously from an unknown cause.”

How do you fight a disease when you don’t understand how it started or what drives its progress?

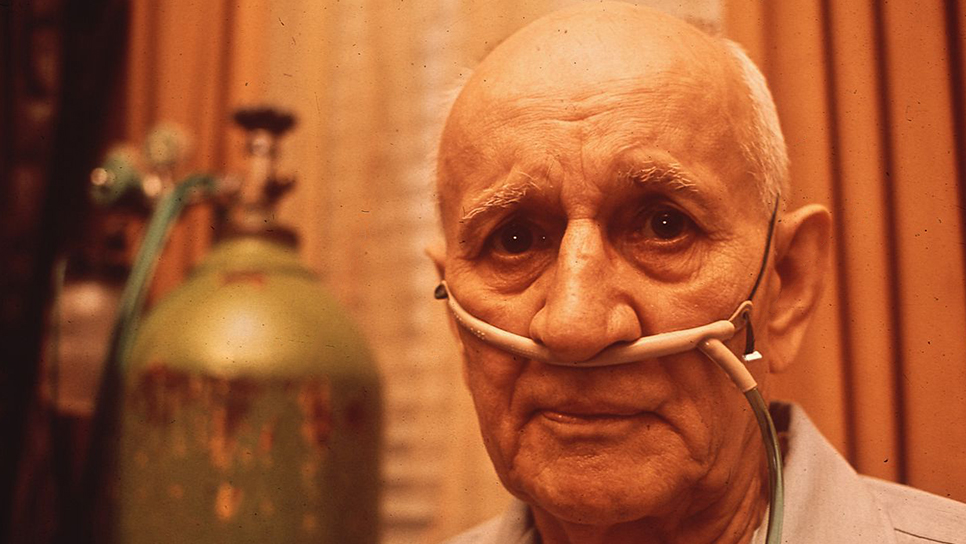

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a progressive, irreversible lung disease, is especially frustrating. What starts as shortness of breath and a dry cough leads progressively to scarring and hardening of the tissue in the lungs. Patients with IPF find breathing increasingly difficult, until, gradually, they cannot breathe at all.

Pulmonary rehabilitation and supplemental oxygen can bring patients some comfort, and a few drugs may slow disease progress somewhat. Younger patients strong enough to undergo major surgery can benefit from a transplant, if a lung is available. But sadly, once a patient is diagnosed with IPF, life expectancy averages between three and four years, with mortality rates higher than most cancers.

The University of Chicago has a strong contingent of researchers and physician-scientists—pulmonologists, immunologists, microbiome specialists, big data experts—studying the disease. The University also has a growing cadre of chemists and molecular engineers focused on creating the cellular and nano-scale tools to unwind the causes of IPF and ultimately operationalize new diagnostic and treatment strategies.

In research reported last year, Catherine Bonham, MD, and Anne I. Sperling, PhD, demonstrated that patients with high levels of a certain immunological biochemical called ICOS in their blood samples had markedly better lung function than those with lower levels. They also found patients with a very low level of a second biomolecule tended to do especially poorly. Assessed in tandem, blood levels of these two substances might offer a valuable diagnostic indicator of IPF prognosis and who would most benefit from early and aggressive disease management.

Interestingly, both substances are attached to and regulate the activity of T-cells, an immune cell known to fight cancer.

The researchers also discovered another tantalizing fact. ICOS levels were exceptionally high—much higher than in the blood—in the lungs and chest lymph nodes of patients with IPF, suggesting some kind of direct connection between ICOS and the disease. “But we don’t understand what these molecules are doing there, or if their response to flood the lungs is helpful,” Bonham said.

With strong institutional expertise in immunology, UChicago researchers are well-placed to unwind the mechanisms involved, which could set the stage for developing more effective treatments. So this week, Joel Africk, President and CEO of the Respiratory Health Association (RHA) visited the University to present Bonham and her team with a grant to advance this work. The RHA called the research “high-quality, innovative, and translational.”

Because UChicago treats a significant number of patients with IPF, the team can now undertake a controlled, longitudinal study to determine whether high ICOS levels in patients is linked to improved survival over the long-term. The team will also look to explore the effects of ICOS directly in the lungs, using lung samples—both from patients with and without IPF—collected and banked laboriously by the team has over many years.

Certainly, the cross-over between the activity of T-cells in both IPF and cancer is exciting. If the disease mechanisms are indeed related, IPF scientists and clinicians will be able to stand on the shoulders of those here and elsewhere driving an explosion of research on using the immune system to fight cancer.

The Duchossois Family Institute is just the kind of shared research environment where knowledge will be pooled and inspire innovative approaches to “idiopathic” diseases. It is an investment that stands to serve thousands, now and for years to come.

Elise Wachspress is a senior communications strategist for the University of Chicago Medicine & Biological Sciences Development office