Abstract

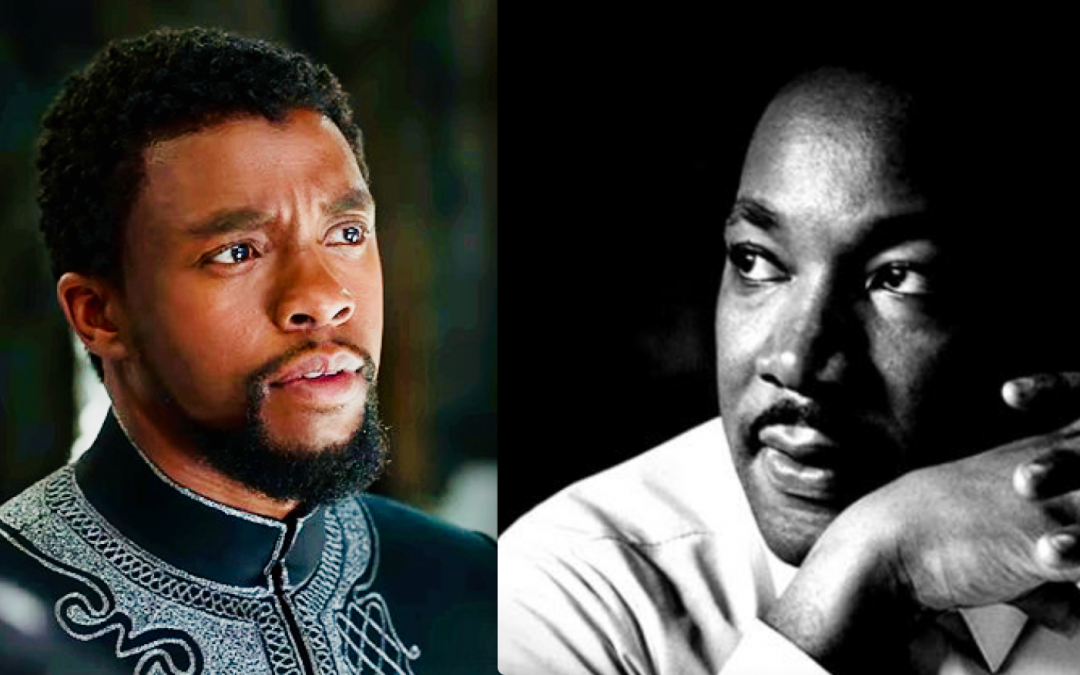

The April issue of the Forum features John Sianghio’s (University of Chicago) essay, “How Black Panther Betrays Dr. King’s Dream.” Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther has conquered the world. Beyond being a box office blockbuster, communities of color and colonized people identify with its depiction of the African nation of Wakanda. Wakanda is a nation at the height of technological, economic, and social advancement. It is untouched by white colonialism and achieves its power, not despite, but because of its blackness. Parallels have been drawn between Wakanda’s king T’Challa—the eponymous hero of the film—and civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr. Both tout blackness as having a power that can benefit the world. However, as empowering an image as Wakanda has become for those who continue Dr. King’s struggle against racism and colonialism in the real world, the very excellences that make Wakanda a beacon of hope may be antithetical to the radical economic and axiological aspects of Dr. King’s legacy. Dr. King regularly condemned capitalism’s veneration of the values of technology, security, prosperity and traditional power. For Dr. King, the valorization of these excellences too often devalue the poor and vulnerable. It is, however, precisely the depiction of Wakanda as a black nation possessed of technology, security (in both the physical and economic sense), and power that give the country its potency and its appeal as a rallying symbol for oppressed cultures. Coogler’s Wakanda is aligned less then with the civil rights message of Dr. King than it is with the contemporary sentiments of figures like Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose weapon of choice against an oppressive system is the achievement of power by black and other colonized peoples. Wakanda can never be the prophetic dream of figures cut in the mold of Dr. King like James Baldwin and Cornel West. Unlike Wakanda, these figures find the strength of their communities not in superiority, but from the unique resilience and unconventional power that historic vulnerability and oppression have engendered.

Read the response below by Joseph Winters (Duke University), “Black (Anti)-Sovereignty, Care, and the Coldness of the Dream.” We also invite you to join the conversation by submitting your comments and questions below.

by John Sianghio

Black Panther fulfills the “need to let [black] children dream, and dream big.” I’ve found no more eloquent summary of the importance of Black Panther than these words from Reverend Otis Moss III. Moss is senior pastor of Chicago’s Trinity United Church of Christ near my home on Chicago’s South Side, and notably the church where President Obama was once a congregant.

I’ve seen firsthand how director Ryan Coogler’s vision of Wakanda has inspired the dreams of black neighborhoods in Chicago. It is important never to forget that Black Panther is a testament specifically to black excellence and black power, but the dream that is Wakanda also reaches beyond the borders of blackness. Colonized communities of all colors connected with the film and its vision of a society untouched by the oppression of white imperialism. I was moved to the core to see the Dora Milaje warriors conspicuously clad in items inspired by the Igorot tribes of my native Philippines. I descend from those tribes through both of my grandmothers. In a film about black power, Coogler gave a nod of solidarity to my people’s struggle against both Spanish and American colonization.

Nevertheless, I am increasingly uneasy with how much I relished the world of Wakanda. At the film’s end, T’Challa (Wakanda’s King and alter ego of “Black Panther”) decides to make Wakanda a force for bettering the lives of the vulnerable by sharing Wakanda’s technology and culture. If the trailers for Marvel’s upcoming Avengers: Infinity War, are an accurate indication, he also commits to use Wakanda’s warriors and weapons to defend the people of earth.

The sentiments driving T’Challa’s benevolent shift in policy are all too familiar to me. They were the motives that led me from the relatively comfortable life of a college instructor to the decidedly uncomfortable post of a scholar serving in a forward-deployed Army unit in Afghanistan. Looking at the results of U.S. intervention in Afghanistan now 17 years after our initial entry, whatever good intentions we had seem now to be less a dream deferred than they are an impossible dream.

Because of my experiences, I can’t help but ask whether a world-wide Wakandan renaissance could fulfill Martin Luther King’s dream. Dr. King called for a nation where character counted over every other value. Wakanda certainly provides a touchstone for colonized communities of color. But does it baptize in blackness the same values of strength, security, and civilization that have historically sanctified white missionary imperialism? Whatever else Wakanda may stand for, it stands first and foremost for the kind of power that Dr. King condemned.

On the one hand, it’s difficult to underestimate the cultural impact of a film like Black Panther. It’s brought Dr. King’s dream of black inclusion back to the forefront of our country’s collective consciousness and even built upon it. For better or worse, Hollywood is still the trustee of our cultural imagination—and Hollywood prefers blondes. When Hollywood does foreground black accomplishment, it comes in the form of black characters breaking barriers. What sets Black Panther apart is that it does not depict people of color simply breaking barriers, but rather setting the standard for the whiter world.

Depicting standard-setting black excellence in a fantasy universe, however, does not mean the film ignores the ongoing struggle people of color in the real world. Perhaps Coogler’s greatest accomplishment is to return the narrative of racial justice to its radical roots. As the world memorializes King’s death this month and sings the praises of liberation, equality, and democracy, Black Panther reminds us that our social contract was signed in blood.

Many think-pieces immediately following the film’s release focused on the surprising sympathy audiences had for the film’s antagonist, the anti-heroic Eric Killmonger. While Wakanda’s newly minted King T’Challa is the embodiment of the wise and strong Guardian of Plato’s Republic, Killmonger’s insurgent claim to the hearts and minds of would-be Wakandans comes through his Ali-esque ability to eloquently express the language of the unheard. Killmonger’s ideology, his zeal, and the lengths to which he was willing to go to achieve liberation for the oppressed struck a dissonant but beautiful chord, especially when contrasted with T’Challa’s quiet resolve and commitment to harmony.

Many think-pieces immediately following the film’s release focused on the surprising sympathy audiences had for the film’s antagonist, the anti-heroic Eric Killmonger. While Wakanda’s newly minted King T’Challa is the embodiment of the wise and strong Guardian of Plato’s Republic, Killmonger’s insurgent claim to the hearts and minds of would-be Wakandans comes through his Ali-esque ability to eloquently express the language of the unheard. Killmonger’s ideology, his zeal, and the lengths to which he was willing to go to achieve liberation for the oppressed struck a dissonant but beautiful chord, especially when contrasted with T’Challa’s quiet resolve and commitment to harmony.

The relationship between T’Challa and Killmonger is clearly meant to evoke parallels between the two towering figures of the American civil rights movement, Dr. King and Malcolm X. Certainly, the debate between the use of soulforce or armed force to achieve liberation is still alive, more so in the charged post-Obama sociopolitical climate that birthed Black Panther. It is a demonstration of the utmost directorial skill that Coogler navigates the nuance of this debate without turning Black Panther from a blockbuster into a lecture. But while T’Challa’s moderation of force seems almost like non-violence compared to Killmonger’s militancy, to dream of Wakanda where the colonized are kings is ultimately to defer King’s dream in more ways than Wakanda’s rejection of non-violence.

Black Panther is a superhero film. It should not have been surprising that it works within the action hero bounds of the genre where violence is a given. But it does try to moderate its use of power with an anti-imperialist message. Adam Serwer notes that “Black Panther does not render a verdict that violence is an unacceptable tool of black liberation—to the contrary, that is precisely how Wakanda is liberated. It renders a verdict on Imperialism as a tool of black liberation, to say that the master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house.” It is here, at the point of its targeted effort at liberation, that Wakanda ultimately betrays King’s dream.

Wakanda works hard to distinguish its power from the imperial power of the colonizer. Even CIA Everett Ross, a white ally and friend of T’Challa, is barked into shamed silence as a colonizer during one of the film’s most hilarious and yet poignant scenes. Nevertheless, Coogler’s vision is permeated by the seemingly inescapable reach of colonialist thinking. Wakanda’s fundamental character is not simply that it is a black civilization, but that it is a technologically superior and unconquerably strong black nation. In glorifying these characteristics, Wakanda is working with and not through colonialist categories and touting as its own the values of an oppressive global system. This is where Coogler’s dream diverges most fundamentally from King’s.

I do not expect that Avengers: Infinity War will show Wakanda planting its flag on the soil of other nations. Nor am I speaking only of the fact that Wakanda is a hereditary monarchy which has been the concern of other critics. In reviewing Black Panther, culture critic Steven Thrasher rightly asks the question “what is a more colonialist ideology than upholding the divine right of kings?” But the answer is not as obvious, nor as damning, as Thrasher makes it seem.

First, there are many systems, indigenous to the colonized peoples of Africa, Asia, and South America where the legitimacy of royal rule was ratified by appeal to the divine. It is not a strictly European or colonial doctrine. More importantly, however, by the time that revolutionary movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America began to agitate for and win their independence, the idea of rule by divine right was passé, more a relic of rhetorical vanity than a value preserved by policy.

Modern colonial administrations justified themselves through the supposed superiority of their civilization and their ability to better manage the affairs of a childlike and savage indigenous population. The legitimacy of rule was based on the advanced nature of their technology, the efficiency of their economy, and the supposed humaneness of their philosophy. Most importantly, Imperialism justified itself through the stability and security that superior arms purportedly provided for both colonizer and colonized.1

Modern colonial administrations justified themselves through the supposed superiority of their civilization and their ability to better manage the affairs of a childlike and savage indigenous population. The legitimacy of rule was based on the advanced nature of their technology, the efficiency of their economy, and the supposed humaneness of their philosophy. Most importantly, Imperialism justified itself through the stability and security that superior arms purportedly provided for both colonizer and colonized.1

Looked at in this way, Imperialism is no longer the concern of any one nation and its viceroy, but has rather more to do with the preservation of a global system and its values. Indeed, When Audre Lorde first gave cultural life to the phrase “the Master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” she was not referring to the physical violence of Imperialism. Lorde was critiquing the more abstract ways in which the imperial project valorizes the strength and high culture of the established institution, and devalues the strength that comes from the vulnerable bearing one another’s burdens and amplifying the voice of those traditionally viewed as weak.

Imperialism is no longer conducted by deploying guns, germs, and steel in expeditions of conquest. Nor is it characterized by blatant apartheid. Instead, political philosopher’s Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri point out that the modern work of Empire is, on its face, far more inviting and inclusive. Like the Pax Romana, modern Empire has a liberal face that welcomes all creeds and races into its dominion. It even pays lip service affirmation to the differences that do not cause conflicts of interest or threaten the system. But the business of Empire is ultimately to manage the stability of the status quo and the hierarchy (racial, social, technological, and economic) that it represents.2 Violence is justified in the name of the commonly held value of civilizational security—both material and social.3 For Hardt and Negri, the contemporary Empire is the global capitalist system and the values that maintain it. Whatever else Wakanda does, it perpetuates this system.

The unprecedented success and acceptance of Wakanda’s racially charged message in some ways represents the co-opting of even radical racial narratives as tools of Empire. Speaking to Goldman Sachs about the importance of making Black Panther, Disney Chairman Bob Iger discussed the importance of racial representation in storytelling in a way that confirms this. “I’m a big believer in that—whether you call it diversity or inclusion. But the bottom line is that doing so is good for commerce. The world is obviously multi-colored, multi-natured, and multifaceted. The more we infuse that into our stories, the better off we are.”

Dr. King’s views on whether the dominant system of capitalism, in its philosophic, political, and not simply economic dimensions can be made consistent with the ends of liberation is one of the most difficult issues with which contemporary interpreters of his legacy must deal. Dr. King warned that under capitalism human beings “are prone to judge the success of [our] professions by the index of [our] salary and the size of the wheel base on [our] automobile rather than the quality of [our] service to humanity.”4

Dr. King’s views on whether the dominant system of capitalism, in its philosophic, political, and not simply economic dimensions can be made consistent with the ends of liberation is one of the most difficult issues with which contemporary interpreters of his legacy must deal. Dr. King warned that under capitalism human beings “are prone to judge the success of [our] professions by the index of [our] salary and the size of the wheel base on [our] automobile rather than the quality of [our] service to humanity.”4

It is a leap too far to imply that Dr. King’s critique of capitalism is a call to asceticism. The iconic Dr. King is a man clad in a perfectly pressed suit on the marble steps of the Lincoln Memorial rather than a hair shirted prophet munching locusts in the wilderness. True to the Gospel he served, Dr. King did not condemn money itself as evil, but rather the love of it.

For Dr. King, the sin of capitalism is idolatry: making the technologically advanced, economically efficient, and unconquerably secure man the highest exemplar of excellence and thus devaluing and disenfranchising the vulnerable. The technological advancement, inclusivity, economic and physical security that are the hallmarks of good governance in the current world climate thus cannot alone bring about the nation of character of which King dreamed. Instead, a year before his murder in a speech condemning U.S. intervention in Vietnam (justified on the grounds of security and prosperity), King argued that “We as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of value.”5

Like the debates between proponents of King and Malcolm X at the height of the civil rights movement, this central question of regarding whether the ends of black excellence and liberation can be found in neoliberal capitalism is perhaps best articulated in the public discussion between two towering contemporary black cultural figures: Ta-Nehisi Coates and Cornel West. It is a debate grounded in black discourse, but with ramifications for every community under the yoke of colonialism.

According to Coates, the systemic oppressor does not fear gangsters, thugs, or even revolutionaries like Erik Killmonger. Rather, what it “really fears is black respectability, Good Negro Government”—the concrete demonstration that black excellence and black skill are equal or even superior to the task of wielding political and cultural power that have traditionally been tightly grasped in the palms of white men.6 For Coates, the Presidential administration of Barack Obama as President of the United States was the pinnacle of “Good Negro Government.” The Obama administration did not work singularly for the benefit of the black man, nor only of the United States as a whole. For Coates, Obama’s administration projected the firm belief that “Good Negro Government . . . could be a force for good in the world.”7 This political commitment manifests in Coates’s artistic vision. As journalist Kwame Opam puts it, Coates’s run as author of the Black Panther comic is “less about superhero squabbles, and more about people—particularly African people—navigating something far more universal: power.”

According to Coates, the systemic oppressor does not fear gangsters, thugs, or even revolutionaries like Erik Killmonger. Rather, what it “really fears is black respectability, Good Negro Government”—the concrete demonstration that black excellence and black skill are equal or even superior to the task of wielding political and cultural power that have traditionally been tightly grasped in the palms of white men.6 For Coates, the Presidential administration of Barack Obama as President of the United States was the pinnacle of “Good Negro Government.” The Obama administration did not work singularly for the benefit of the black man, nor only of the United States as a whole. For Coates, Obama’s administration projected the firm belief that “Good Negro Government . . . could be a force for good in the world.”7 This political commitment manifests in Coates’s artistic vision. As journalist Kwame Opam puts it, Coates’s run as author of the Black Panther comic is “less about superhero squabbles, and more about people—particularly African people—navigating something far more universal: power.”

Coogler’s Wakanda benevolently marshaling its technological superiority, economic efficiency, and even armed security for the benefit of the world is a projection of Coates’s vision of “Good Negro Government” on the big screen. In many ways, it is a blacker ideal of an Obama era America, as hyperreal an American dream as Baudrillard’s Disneyland.8 It is also then vulnerable to the same critiques as the United States and the motives for which it wields power. The claim that the U.S. ostensibly will use its power for the prosperity, security, and stability not simply of its own society but for the stability of the Pax Americana is belied by the continued inequality imposed on the periphery of the system. A Pax Wakanda would be worse. Placing the white man’s burden on the backs of black or brown societies is a double form of imperial violence.

The work of Cornel West, whose seminal work Race Matters celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, provides an important caveat to those who reduce liberation to putting black bodies in superhero costumes or political power suits. West acknowledges that “self-respect and self-regard are realms inseparable from…political power and economic status,” but they are not identical.9 It is important, but not sufficient, to see “black faces in high places.”10 Simply touting black success denigrates the value of the vulnerable in the vision of liberation. West maintains, “as a people, we, at our best, [have] always been concerned about all of us––not just the top, highly successful ones. I have nothing against black success, but I can’t stand black success when it generates an indifference toward black poor people.”11

Wakanda is West’s “black faces in high places” on a national scale. Its engagement with the rest of the world is not to ennoble formerly colonized societies, but to show them an ahistorical and impossible ideal of black supremacy. When T’Challa is asked at the United Nations “what can a nation of farmers offer the world?”, the twinkle in the eyes of the principal characters seems to imply, ‘Ah, but we are not a nation of farmers. Our society is more powerful, better resourced, and more humane than yours.’ In other words, our black society is superior to your white one.

But what of the nations of farmers? Do they not have value as they are? What of the kids from Oakland with which the film opens and ends? Is it enough to show them that black people built and own the most advanced jet in the world? Is it enough to show them that they can become the most powerful person in the world if power and excellence continue to be measured in technological, economic, and military terms? Is this what it means to dream big? If it is, it is not Dr. King’s dream.

Rather than speaking truth to power, Black Panther makes power a universal truth—life-giving for both colonizer and colonized. Both T’Challa and Killmonger agree on this—their conflict is simply on how to responsibly exercise their supremacy. For West, however, any account of black supremacy in order to counter white or colonial supremacy “reveals how obsessed one is with white supremacy.” Rather than something empowering, such a preoccupation is “crippling for a despised people struggling for freedom.” A counter-vision of liberation, black or otherwise, must be found—one that shows how power may be drawn from vulnerability rather than simply being drawn out of it. It is the vision of a prophet, not to make all people kings, but to be the voice of the people in the ears of the king.

In America, there has been no voice more prophetic than James Baldwin’s. For Baldwin, the common experience of oppression felt by “pimps, whores, racketeers, church members and children” is the very thing that breeds “the zest and joy and capacity for facing disaster” that eventually becomes “a freedom that is close to love.”12 In the same breath he condemns the “[p]riests and nuns and school-teachers” helping “to protect and sanctify power.”13 And it is specifically Wakanda’s type of power, with its excellence in industry, economy, technology, and arms of which Baldwin is most wary.

In America, there has been no voice more prophetic than James Baldwin’s. For Baldwin, the common experience of oppression felt by “pimps, whores, racketeers, church members and children” is the very thing that breeds “the zest and joy and capacity for facing disaster” that eventually becomes “a freedom that is close to love.”12 In the same breath he condemns the “[p]riests and nuns and school-teachers” helping “to protect and sanctify power.”13 And it is specifically Wakanda’s type of power, with its excellence in industry, economy, technology, and arms of which Baldwin is most wary.

Wakanda is at the height of human achievement, surpassing any of the great powers of our contemporary world in all the areas they hold dear. But Baldwin writes: “We human beings now have the power to exterminate ourselves; this seems to be the entire sum of our achievement.”14 Baldwin’s warning is not simply for white men or black men. It is a warning against the human tendency toward valorizing those things which have brought us to the brink of our own destruction. It is a warning against thinking of Wakanda as an ideal, even for those of color.

Black Panther is, without question, the film most responsible for spurring the discussion regarding what liberation, power, and prosperity mean for black communities. But another film that generated buzz at this year’s Oscars perhaps better captures the spirit of an alternative vision of black power—one more in line with the prophetic visions of West, Baldwin, and King.

Watu Wote [All of Us] is a Kenyan-German film directed by Katja Benrath, a German filmmaker. Its production relied heavily on alumni of the Africa Digital Media Institute, a Kenyan film school.15 The film tells the true story of Muslims who protected Christians during a terror attack perpetrated by Al-Shabab. The heroes of this story had no superpowers. They were teachers, mothers, students, and water sellers. They did not come from the most advanced or stable society on earth. Their power and their heroism came not out of their superiority, but through their mutual vulnerability.

The courage and power of these heroes and the beauty of the film resonates beyond the borders of Kenya. But it is, importantly, a story that could only have taken place and come out of Kenya. It is a film that acknowledges the universal concerns of power, pride, and humanity, while celebrating unapologetically the beauty and uniqueness of a black society. It captures a moment where the most vulnerable demonstrate that the greatest human power is not achieved through technology, economy, or arms. Rather the film puts forth a vision of power that emanates from the human will to love and care for one another through and because of rather than despite the fragility of our common human condition. ♦

John Sianghio is a Ph.D. student in religious ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Formerly he was Assistant Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at Trinity Christian College. As a political scientist, he served as an embedded asset advising U.S. Army units in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He lives on the Southside of Chicago with his wife and five-year-old son.

John Sianghio is a Ph.D. student in religious ethics at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Formerly he was Assistant Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at Trinity Christian College. As a political scientist, he served as an embedded asset advising U.S. Army units in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He lives on the Southside of Chicago with his wife and five-year-old son.

Response: Black (Anti)-Sovereignty, Care, and the Coldness of the Dream

by Joseph Winters

The release, and overwhelmingly positive response to, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther demonstrates familiar patterns regarding cinema, blackness, and affect.16 Black people (and other populations) love to see triumphant, heroic depictions of black people on the screen, a tendency that betrays an enduring thirst for these kinds of images. Therefore, the palpable excitement that the film continues to generate should not surprise us even as it warrants its own study and examination. One feels this excitement when people throw up the “Wakanda forever” sign or have intense conversations about the layered tropes in the film (colonization, extraction of indigenous resources, technology as magic, the “primitive” vs. civilization, death and home, black woman as warrior and protector of male sovereignty, etc.). Similarly, one experiences the film’s cultural resonance when hearing music from the soundtrack or seeing actors from the film in music videos, on talk shows, at sporting events, etc. Yet this Black Panther moment, this celebration of a black film that purportedly urges black children to “dream big,” does not foreclose a critical engagement with the film. As Jared Sexton reminds us, recent films with black men playing the main roles often reproduce prevailing racial fantasies and strategies of containment.17 These strategies can go undetected when black liberation is conflated with heightened black presence within popular culture and increased celebrity power.

John Sianghio’s provocative essay, “Why Wakanda Betrays Dr. King’s Dream,” works with the guiding premise that black films often reinforce dominant logics and imaginaries even when, or especially when, they are celebrated as progressive and uplifting. To be sure, Sianghio acknowledges that “it’s difficult to underestimate the [positive] cultural impact of a film like Black Panther.” At the same time, he insists that “Coogler’s vision is permeated by the seemingly inescapable reach of colonial thinking… In glorifying [technological superiority and unconquerable strength], Wakanda is working with and not through colonialist categories and touting as its own the values of an oppressive global system.” For Sianghio this attachment to, and celebration of, sovereignty and its accompanying operations “diverges most fundamentally from King’s dream.”18 While cousins T’Challa and Killmonger both seem to be enamored with the sanctity of sovereign power (they simply disagree on how to disperse and allocate the vibranium that would give oppressed peoples superhuman abilities), Sianghio looks to the black prophetic tradition—namely King, Baldwin, and West—for an alternative conception of power. This is a notion of power that is “drawn from vulnerability” and the capacity to love rather than the will to control, impose, accumulate, and contain.

Sianghio is right to see connections between Wakanda’s potential “gift” to the world and US strategies that justify empire and erasure in the name of gift, in the name of spreading “power for [global] prosperity, security, and stability.” While there is much in the film, particularly its ending, that positions Wakanda as the black mirror of US sovereignty (while suggesting at times that Wakanda is more advanced and civilized than the United States), we might look for moments when something besides, or beside, the logic of sovereignty is being visualized. Here I take seriously Kara Keeling’s analysis of cinema in which she contends that film “works to order, orchestrate, produce, and reproduce social reality” while also “retaining the potential to manifest an alternate perceptual schema that could perfect a different social reality.”19 In other words, films are often successful in tightening our investments in “common sense” but occasionally they strike us with images and sounds that depart from the commonsensical.

Think for instance of the scene in which T’Challa holds and embraces the body/corpse of Killmonger immediately after the protagonist puts a knife into his cousin. This moment of touch, the image of the King cradling the corpse of his adversary/kin, resembles the Pieta, the image of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of Jesus. What is important here is how this cradling image adumbrates the intimacy between life and death, the sovereign and the villain (both exist at the edges of the law), order and monstrosity. In other words, the intimate moment reminds us that T’Challa’s rule, like his father’s, relies on the repetition of violence, the erasure of those that signify antagonism, tension, and the unassimilable. There is an intimate relationship between the preservation of life and (dis)order and the extension of violence. Why is this important? Because the nation-state, as Foucault powerfully contends, justifies killing populations by drawing a line between those who are worthy of life and those worthy of death. When this gets blurred, another set of possibilities beside nation-state power present themselves to us.

Seeing T’Challa momentarily “care for the dead” conjures up Christina Sharpe’s practice of “wake work,” a term that signifies vigilance toward the dead, including the socially dead who endure the afterlife of slavery.20 Wake work involves an ongoing interaction with those who the nation-state kills twice—through racist practices that justify slavery, war, and occupation in the name of progress, civilization, and democracy; through redemptive narratives that forget, minimize, or attempt to compensate for this violence.21 When Killmonger tells T’Challa to throw him into the sea, to place him with the ancestors, he invokes a tradition that redefines freedom, flight, and home. Similar to the kidnapped Africans who escaped the terror of the Middle Passage by jumping overboard, by flying home, Killmonger prefers to return to the dead, to be at home with those buried in the ocean without a funeral. His request introduces a set of haunting questions. If Sianghio rightly contends that nation-state sovereignty “in black” still leaves us mired in pernicious fantasies of power and supremacy, what kind of (blackened) power is associated with care, wake work, intimacy with the dead, refusal, escape, etc.? What does power look like that is not grounded and settled but that is, in Hortense Spillers’ language, “suspended in the oceanic”?22 What if the desired telos of black strivings is not the heights of power but the opaque depths of the sea? Perhaps these queries and yearnings can only be satisfied in a dream … or in that brief interval between dreaming and waking up. ♦

Joseph Winters is an assistant professor of Religious Studies with a secondary position in the Department of African and African American Studies. His interests lie in African-American Religious Thought, Religion and Critical Theory, Af-Am Literature, and Continental philosophy. Overall, his project is concerned with troubling and expanding our understanding of black religiosity and black piety by drawing on resources from Af-Am literature, philosophy, and critical theory. Winters’ first book, Hope Draped in Black: Race, Melancholy, and the Agony of Progress (Duke University Press, June 2016) examines how black literature and aesthetic practices challenge post-racial fantasies and triumphant accounts of freedom. The book shows how authors like WEB Du Bois and Toni Morrison link hope and possibility to melancholy, remembrance, and a recalcitrant sense of the tragic.

Joseph Winters is an assistant professor of Religious Studies with a secondary position in the Department of African and African American Studies. His interests lie in African-American Religious Thought, Religion and Critical Theory, Af-Am Literature, and Continental philosophy. Overall, his project is concerned with troubling and expanding our understanding of black religiosity and black piety by drawing on resources from Af-Am literature, philosophy, and critical theory. Winters’ first book, Hope Draped in Black: Race, Melancholy, and the Agony of Progress (Duke University Press, June 2016) examines how black literature and aesthetic practices challenge post-racial fantasies and triumphant accounts of freedom. The book shows how authors like WEB Du Bois and Toni Morrison link hope and possibility to melancholy, remembrance, and a recalcitrant sense of the tragic.

- Edward Said, Orientalism: 25th Anniversary Edition (New York: Vintage, 1994), 206-207. ↩

- Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. Empire (Boston: Harvard, 2000), 199-200. ↩

- Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: Penguin, 2004), 20. ↩

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “Paul’s Letter to American Christians,” Sermon delivered to the Commission on Ecumenical Missions and Relations, United Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. Pittsburgh, PA. June 3, 1958. ↩

- Martin Luther King, Jr. “Beyond Vietnam”. Speech delivered at Riverside Church, New York, NY. April 4, 1967. ↩

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy (New York: One World, 2017), xv. ↩

- Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power, xv. ↩

- Jean Baurdillard translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor: Michigan, 1994), 12. ↩

- Cornel West, Race Matters: 2nd edition (New York: Vintage, 2001), 95. ↩

- Cornel West, “Neo-liberalism has failed us.” Interview by Hope Reese, JSTOR Daily. December 25, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/cornel-west-interview/ ↩

- Cornel West, “Neo-liberalism has failed us.” Interview by Hope Reese, JSTOR Daily. December 25, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/cornel-west-interview/ ↩

- James Baldwin. The Fire Next Time (New York: Vintage, 1993), 41. ↩

- Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, 46. ↩

- Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, 57. ↩

- Matt Pickles, “Kenyan Film School Takes on Hollywood for an Oscar,” BBC News. March 1, 2018. http://www.bbc.com/news/business-43206457 ↩

- The title of this response alludes to Arthur Jafa’s documentary Dreams are Colder Than Death. ↩

- See Sexton, Black Masculinity and the Cinema of Policing(New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2017). ↩

- For a discussion of the complexities of sovereignty in the film, see Lubiano, “Cry T’Challa, You are a King: The Remaking of the Sovereign,” http://www.newblackmaninexile.net/2018/04/cry-tchalla-you-are-king-remaking-of.html ↩

- See Keeling, The Witch’s Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 11, 15. ↩

- See Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). ↩

- Here I am thinking about Walter Benjamin’s essay, “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” ↩

- See Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” Diacritics 17.2 (Summer 1987): 72. ↩