“Several times on every page the reader is released–like a trapeze artist–into the open air of imagination… then caught by the outstretched arms of the ever-present next panel! Caught quickly so as not to let the reader fall into confusion or boredom. But is it possible that closure can be so managed in some cases–that the reader might learn to fly?”

–Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1994), 90.

In this entry, I would like to focus most directly on the movement-image and time-image. Specifically, I would like to explore the modes of linkage that at once connect them to and expand the plane of immanence. To do so, I will turn once more to work in the field of comics. To say that the fundamental operation of comics is the representation of time as space is a truism in comics studies. Is there room, however, to assert that it is possible for time itself to enter the picture (or image)? Perhaps, and perhaps this is what McCloud implies (though likely unwittingly) when he suggests that there might be an alternative to the way the reader is “caught” by the outstretched arms of the next successive instant. Can space, and the contents of the image bound on each side by the frame, be managed (or unmanaged) in such a way that the comics panel becomes something other than a discrete moment of chronologized time? I believe so, but first it is necessary to indicate how the movement-image emerges in the comics form.

The movement-image, as montage and sequence, is without doubt (but with qualifications) the classical form of the comic strip as it developed during the proliferation of mass media.[1] In the newspaper strips of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the inevitable repetition of action—often a physical gag at the end of the strip—provided a structure for comics that did not merely mark the conclusion of the narrative, but rather shaped the strip in its entirety. The direction of reading, the iconic arrangement of its parts, and the number and order of its panels found significance through the transcendental power of the final gag. This is true even of highly regarded works that approached the avant-garde in their manipulation of movement and sequence. Winsor McKay’s Little Nemo (1905-1926), for instance, about a boy’s fantastical adventures in the land of dreams, always ends with Nemo waking abruptly in his bed. Likewise, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat (1913-1944) consistently revolves around the moment when Ignatz Mouse launches a brick at the head of his lovelorn admirer, Krazy, who takes each lump as a sign of Ignatz’s devotion. This fact, of course, does not in the least minimize the importance of these works. Deleuze, following Bergson, writes that “through movement the whole is divided up into objects, and objects re-united in the whole, and indeed between the two ‘the whole’ changes” (MI 10). The open whole that changes through the variation of its parts is the indicator of universal variation. How does this process make itself known in comics, even in the early strips that I relate to the movement-image? A brief example is in order.

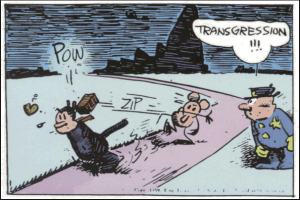

A single image from Krazy Kat should suffice to make clear the role of the movement-image in comics. My own work is largely focused on the inter-iconic relations between panels—on what I see as the radical potential of the networked page as opposed to the linear sequence—but, for the sake of brevity, and to follow Deleuze in demonstrating the indication of the whole by the set, I will focus on a single panel (Figure 1).

In this image, we can see the tripartite elements of perception, affection, and action that make up the movement-image. Indeed, here the elements form an inseparable circuit, a sort of perpetual movement machine. The form of the image is circular: we begin at the top left (following the typical vector of reading), where the violent “POW” that leaps out from the static background suddenly dissolves the calm evening sky. Our eyes could drift down to the impact that caused the sound, the brick hitting Krazy’s head, but to do so would ruin the effectiveness of the strip—the inevitable gag must wait until the end, even though the initial “POW” has already signaled its occurrence. Instead we let our eyes be drawn along the road that seems to begin at the sound itself. We are led, again along the typical vector of reading, to Offissa Pupp, the police officer dog who tries to protect Krazy from harm. The road we’ve followed leads directly into Pupp’s eyes—he is pure perception. “Living beings allow to pass through them,” Deleuze writes, “those external influences which are indifferent to them; the others isolated become ‘perceptions,’ by their very isolation” (MI 62). Pupp isolates the violence of the inevitable brick; for him, it is “Transgression!!!” and nothing else, though, as we will see, the role of the brick is far more complicated than that. In this image, Pupp is frozen at one end of the sensory-motor situation. He, like the reader, is only a witness to the event. However, he also reassures us of the unity and authority of our subjectivity. Because the knowing reader’s perception is different from Pupp’s (it circumscribes his own), our perception of his perception becomes a source of laughter.

Moving on from Pupp, we find Ignatz Mouse’s hand (which has always already launched the brick) blocking the road itself, arresting the movement of the reader’s eye and demanding its subordination to the action of the flying brick. We may think of Ignatz as pure action, arm always outstretched, leg lifted, always having just released his missile. We can no longer simply follow the road that curves through the panel—we must follow the path of the brick itself, indicated with ‘speed lines’ and a dynamic “ZIP.” Finally we reach Krazy Kat, who—in a very simplistic sort of way—marks the image of affection. Krazy’s position here is neither that of action (s/he is being acted upon), nor purely that of perception (it is significant that in the visual medium of comics, Krazy always faces away from the brick). Of course, affect here is not a simple subjective emotion, despite the heart that we see emanating from Krazy. As Deleuze tells us, “there is inevitably a part of external movements that we ‘absorb,’ that we refract, and which does not transform itself into either objects of perception or acts of the subject; rather they mark the coincidence of the subject and the object in a pure quality (MI 65). Here it is the brick itself that is transformed; freed from Ignatz’s hand as an object of aggression, it is re-fashioned mid-flight into a sign of love. The heart on the far left, at the end of the reader’s journey, matches the color and trajectory of the brick exactly, so that it seems to have physically transformed as it passes through Krazy. Here, then, the brick itself seems to occupy the “zone of indetermination” that Deleuze says is the mark of the subject (MI 66). It is overdetermined, divided between perception, affection, and action, cutting through the center of the image and warping the temporality of the scene into a spiral that uncurls in its wake. It is singular and still, yet it is a movement-image.

As I began this close reading, I noted that the image from Krazy Kat forms a sort of circuit, a perpetual movement machine. Indeed, our path through the image leads us finally from the brick back up to the sound it makes, the “POW” that re-initiates the cycle. But if this were wholly true, what chance would there be of a direct image of time in the comics medium (or in any work of art)? There is something in the movement-image that is not equal to itself… some element of excess where the actual and the virtual collide. I propose that this element emerges in the paradoxical and simultaneous co-existence of the heart and the “POW” onomatopoeia. This is the true “gap” whose presence is diagetically echoed by the brick. For the gag to be truly complete, the reader must read in the direction of the heart (to the left), the sign of Krazy’s joyful acceptance of the brick as a token of love. At the same time, the brick’s physical collision with Krazy must lead upwards, toward the sound that accompanies it. It is true that the eye can take in both these moments at once, but it cannot do so and remain loyal to the vectors of motion that structure the strip. To follow the brick straight to the “POW” means disregarding the heart. Conversely, to follow the brick to the heart means having to reverse the trajectory of reading, to go backwards—violating the ‘time as space’ truism of the comics image—to the brick and then up to the “POW.” This is where recollection, incompossibility, and the co-existence of presents make their presence felt. The sensory-motor flux is troubled, and the heart points outward toward the out-of-field. Herein lies the limitation of the movement-image on the comics page. Herein waits the germ of true difference in the cyclical image.

Once again, I’ve set myself up for a thesis that I did not have space to put forth. The time-image as it may appear on the comics page is a result of the mode of inter-iconic linkages between panels and across pages. This much I’m sure of. I’ll have to prove it to you next time.

[1] Because comics are drawn rather than filmed, they make different claims of indexicality. They are incapable of the “any-instant-whatever” of cinema and are bound to present privileged moments. This is a complication that must be addressed if one wishes to explore comics through the work of Bergson or Deleuze. I hope I’ll have the opportunity to do so at some point.

In me you have a good reader, because I believe that George Herriman is one the greatest philosophers of the 20th century!

This is a beautiful and detailed reading of a single image that demonstrates with great precision the circuits of movement through perception and action to affect that can circulate in a still image. And in no way do I take your analysis to be metaphorical: these are vectors, directions, colors, and segments that truly set the image into movement with respect to reading. While the plane of immanence organized by cinematographic potentials for space and time, and the signs and Ideas generated out of that plane, are privileged for Deleuze, your example shows how Deleuze’s account might be deepened and extended in other media, and not only photography. It is yet another challenge to what we call an image and how we believe images to function.

Finally, to think of how time-images might emerge out of comix, it might be interesting to investigate the function of the frame and out-of-field in relation to sequence. Is the frame open or closed; does it contain or produce? Is there a predictive series are an indeterminate series? Are frames organized in sequence or associated in constellations linked by determined or contingent vectors? My intuition is that D&G’s chapter on the rhizome might be very helpful when we get to it.