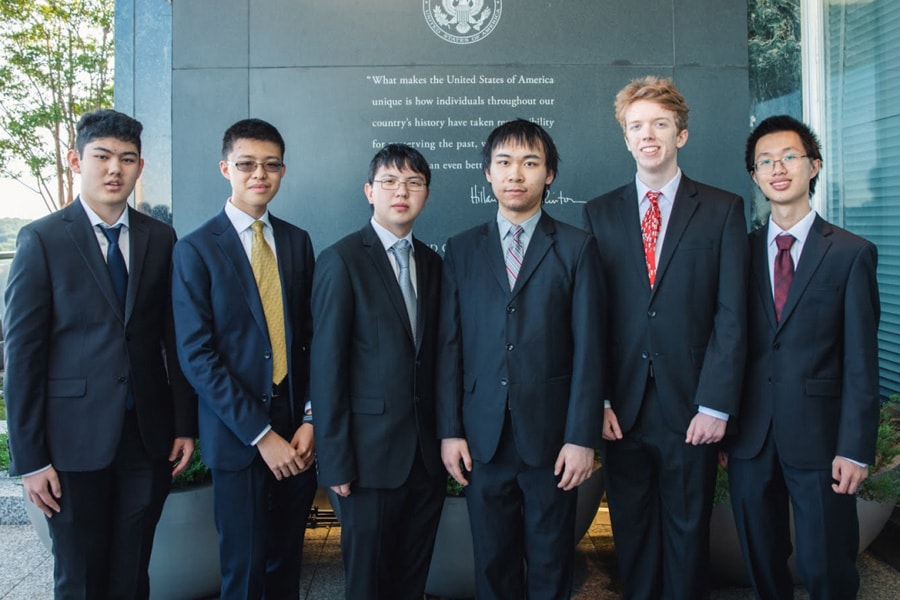

International Math Olympiad (IMO) Winners

Ever since I was a child I’ve taken a rather quantitatively focused path both in academics and work. I’m not sure where it started – whether it was familial, cultural, community influence, genuine passion, or a mixture. I participated in math competitions, went to a well regarded STEM high school, and took advanced math and computer science classes. Throughout, I felt comfortable, and was praised for my success, yet it was also expected as an Asian male. At UChicago I’ve had a similar experience. Throughout my life however, the gender disparity has always been overwhelmingly evident. The qualifying pool for the American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME) is 22% female. The next level, the United States of America Mathematical Olympiad (USAMO), is only 10% female every year. Even my high school was 70% Asian and 60% male. Seeing these trends, I’ve found math is a very pointed case of both cultural influences on expectations, as well as intersectionality between race and gender.

This past quarter in my ordinary differential equations (ODE) class, when I walked into class the first day, around a third of the class was female. One of my friends in the class immediately commented

Wow this is so nice, there’s so many girls here.

This statement, indicative of a larger systemic pattern, also raises a number of interesting questions. Why is the number of women in math so small? Why is it comforting to have those of a similar gender in a higher level math class? To show that even at a more liberal college, this is still an issue, one only has to view the UChicago mathematics faculty page.

Interestingly enough, gender disparity seems to grow with the level of math. Among other standardized tests, there is still disparity, but when viewing competition math, beyond the 99th percentile, the male to female ratio exceeds 10-1. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (U.S. Department of Education), women earned 57%, 60% and 52% of all Bachelor’s, Master’s and Doctoral degrees respectively in the U.S. in 2013-14. However, women earned only 43%, 41% and 29% of the Bachelor’s, Master’s and Doctoral degrees respectively in mathematics and statistics in the U.S. in the same year.

One of the first thoughts I had was that perhaps we would see a similar reflection both in cultural education and concepts in math like Richardson demonstrated in biology in “How the X and Y Became the Sex Chromosomes” and Nettleton’s study of YouTube videos describing sperm and eggs.

From memory, and also browsing studies online, however, I realized that almost none of mathematics’ concepts are gendered whatsoever. Perhaps the nature of exact description and guise of objective truth prevents any explicit association with gender. Yet in history, math has been viewed along with philosophy as an explicitly male venture. To explore the causes of these trends, a study in 1999 by Walsh et al. showed that the gendering of characters within math problems themselves did not affect test performance significantly. Interestingly, however, women scored lower than men when they believed that the test had previously shown gender differences. So was it then a cultural cause and identity question that caused these changes?

Going back to my ODE’s class, perhaps my friend felt more comfortable because she felt like she belonged in that specific academic environment. Exploring the potential effect culture can have on performance and interest, I found that the math and reading gap vastly differs in different countries. While on average, around the world, females tested better in reading and males tested better on mathematics, it differed significantly by country. These trends are similarly reflected in positions both in industry and academia.

Perhaps the difference can be explained in a cycle of expectations, public perception and sense of belonging in specific environments. The cause found in the study I viewed was what they termed the gender stereotype threat. By performing well in math, males are performing their gender and thus females are discouraged from doing this performance. This can be found at all levels of school. Even in high school, when I took more advanced computer science and math classes, classes of around 30 people only had 3-4 girls. This perception, at least anecdotally, seems ingrained in our culture.

When some of my friends from home visited me here at UChicago, I introduced them to a number of my friends who were math majors. When they met males, they treated it as normal. When meeting females, however, the statement I heard most was along the lines of

That’s so cool that you’re studying that. What do you like about it?

While perhaps an innocent statement, I also read it as a statement that by studying math, females are breaking the expectations of society. It implies that there has to be a reason for them to want to do so other than it being natural, or what they want to do.

Race and Gender

Intersectionality is also a word that has constantly come up in my mind when thinking on my experience and observations. When viewing how different women performed on tests under pressure of expectations, it was found that Asian women’s performances decreased far less than others. If we are to accept that the decrease in performance is strongly influenced by a historical expectation of poor performance, then perhaps the expectation of Asian identity is strong enough to outweigh the expectation of female identity. We then see a race disparity within the already existing gender disparity.

My thoughts are that performance and motivation from a young age is then driven by a sense of belonging. While perhaps mathematics is a performance of male gender, it has also become a performance of race in popular culture. Thus the statistics of success can be attributed to cultural expectations. This might explain why in some of the largest Asian countries, the disparity in performance almost disappears. To solve this issue in math, then again comes back to culture and societally decided norms.

Industry and Clubs

In a work setting, I also have seen many examples reflecting ignorance of the existence of intersectionality. In the same way that we have differentiated historically white femininity from femininity as a whole, we can perhaps see similar trends in math based industries. I’ve interned in quantitative trading the past few years and there has been a push for more diversity on the gender front. The focus however is purely on gender without regard to race as well. What we see then is also a reflection of the study regarding race and gender. When seeing the turnouts of diversity events, often they accomplish the goal of gender, without regard to race. Thus, while each category is represented individually, there is still no true intersectional representation.

Quantitative fields seem to be in a stage lagging behind the humanities by a number of years. Even in applications for quant clubs here, the performance of candidates has no correlation to their background, however, the number of applicants from non male identifying individuals is incredibly low. This further indicates that it is a cultural and systemic lack of belonging and self selection that has largely driven these trends rather than other factors. As a whole it is fascinating that a field as “objective” as math is still driven by societal gendering of roles and to change that, the culture and idea system itself must change.

I really liked your analysis about the roles gender and race play in the field of mathematics. I agree with the point you mentioned about childhood experience shaping a sense of belonging. One of my professors for Mind, Susan Levine, researched disparities in learning mathematics in young children. During our discussions, her research would frequently be brought up. One discussion we had was about the language used when talking to young girls about their math performance. Teachers often seem surprised and praise young girls when they are really good at math. The surprising tone some teachers may have can discourage young girls from pursuing math. We also discussed how the connotation behind some comments is that boys are the standard to be compared to. This is similar to the example you provide of your friends thinking it’s really cool when a girl studies mathematics.

I recall reading a study about this phenomenon, but more broadly applied to the STEM field in general. The author theorized that these subjects already seem to have a “bro culture” to them that discourages women from trying to enter the field. This theory is supported by the fact that certain subjects have lower numbers of women compared to others, most notably engineering having a very low number of women. I wonder if this phenomenon has to do with sex or if its more gender related. It seems like when people learn their gender, they integrate what sort of things the gender is supposed to do (e.g. math) into their brain, which shapes their actions. So then, would a transgender person then have the same relationship with math as their sex or as their gender? As trans girls are growing up, they are likely met with messages for boys, so would they be more confident in their ability do math or would they be hesitant to do math because girls aren’t supposed to do math and they identify as girls.

I thought this subject was very thought provoking, and I really liked how you tied in your personal experiences in to it. Hearing about the statistics on women in math really shocked me, because I never really remembered any significant gender disparity in any of my math classes in high school—in fact, I remember the most competent math student in my grade and the grade below both being girls. I wonder if perhaps the fact that I went to a public school in a wealthy area affected this.