It’s not all that easy to describe what I do as a historian. Partly, that’s a function of the farsightedness that tends to afflict anyone who is so familiar with what they do that they have a hard time grasping how to explain the essential elements of it to someone “on the outside.” But it’s also a product of the historical discipline itself, since our methodology is often less defined and, I think, more heterogeneous than that in other disciplines. If, however, there is a core element of what historians do, then I think it has to be archival research.

That sounds simple enough, but it depends on some understanding of what an archive is. For better or for worse, that’s not all that clear-cut. Especially with the growing proliferation of digitized sources, it is getting both harder and more necessary for historians to explain how they approach disparate collections of potential source materials as archives and answer the questions that must be asked of any archive: Who “built” it? For what purpose? Whose voices are included/excluded? etc. Digitized sources raise further questions, particularly since it is increasingly likely for sources to exist and be accessible in different kinds of media.

To illustrate this “problem” (I mean it in a constructive, not negative way), I want to give an example from my own research. Local gazetteers are one of the main sources I (and many other scholars of Chinese history) use for research. Gazetteers are basically encyclopedias of the geography, customs, famous people, etc. of a given administrative unit. Like an encyclopedia, they are obviously useful for reference purposes, but they are also interesting as objects of study themselves. (There’s a recent book about this by Joe Dennis.) I use them in both ways.

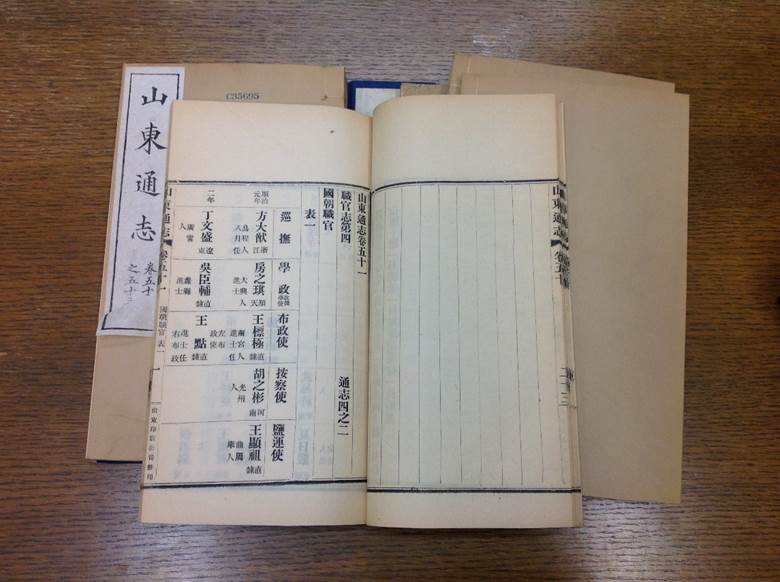

Paper copy of the 1915 Shandong Provincial Gazetteer

I’m not going to lie, it’s pretty cool flipping through thousands of pages of old Chinese documents. It’s the kind of thing that makes you feel like a “real” historian. Paper versions of gazetteers are not the most convenient, though. They can be thousands of pages long, and even if you know what you’re looking for and understand how the gazetteer is organized, it can take a while to find the information you want in a single text, let alone across multiple gazetteers. Additionally, reading them in paper form is no piece of cake, and transcribing important parts is a time-consuming, albeit not altogether unrewarding, task.

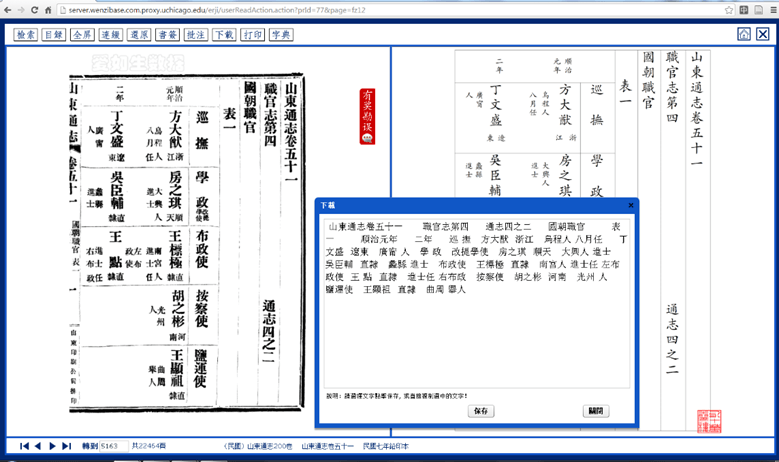

Digitized version of the same gazetteer in the Erudition database

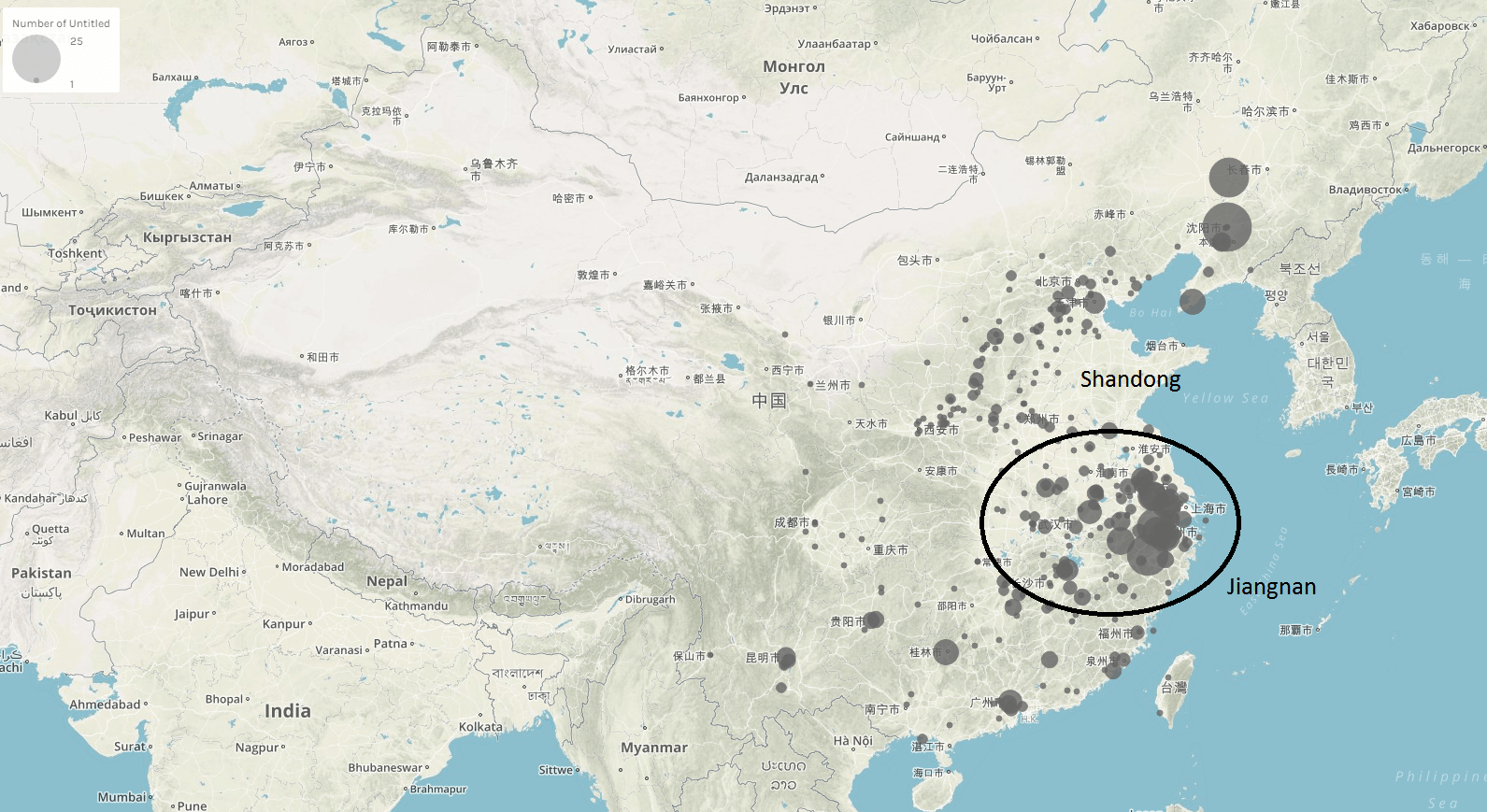

Fortunately, the University of Chicago has purchased access to a database of digitized gazetteers that has opened up new possibilities for my research. For one thing, I can search for keywords across the entire database, which effectively expands the range of sources I can feasibly consult exponentially. Additionally, I can copy and paste text into other applications, making it much easier to collect information and read extracts. (e.g. I can copy and paste obscure characters into an electronic dictionary rather than writing them out by hand/mouse.) Among other things, this has made it possible to quickly compile a spreadsheet of the names and home places of officials who served in Jinan and are recorded in gazetteers, which, using some other tools, I can visually map.

Home places of officials who served in Jinan during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

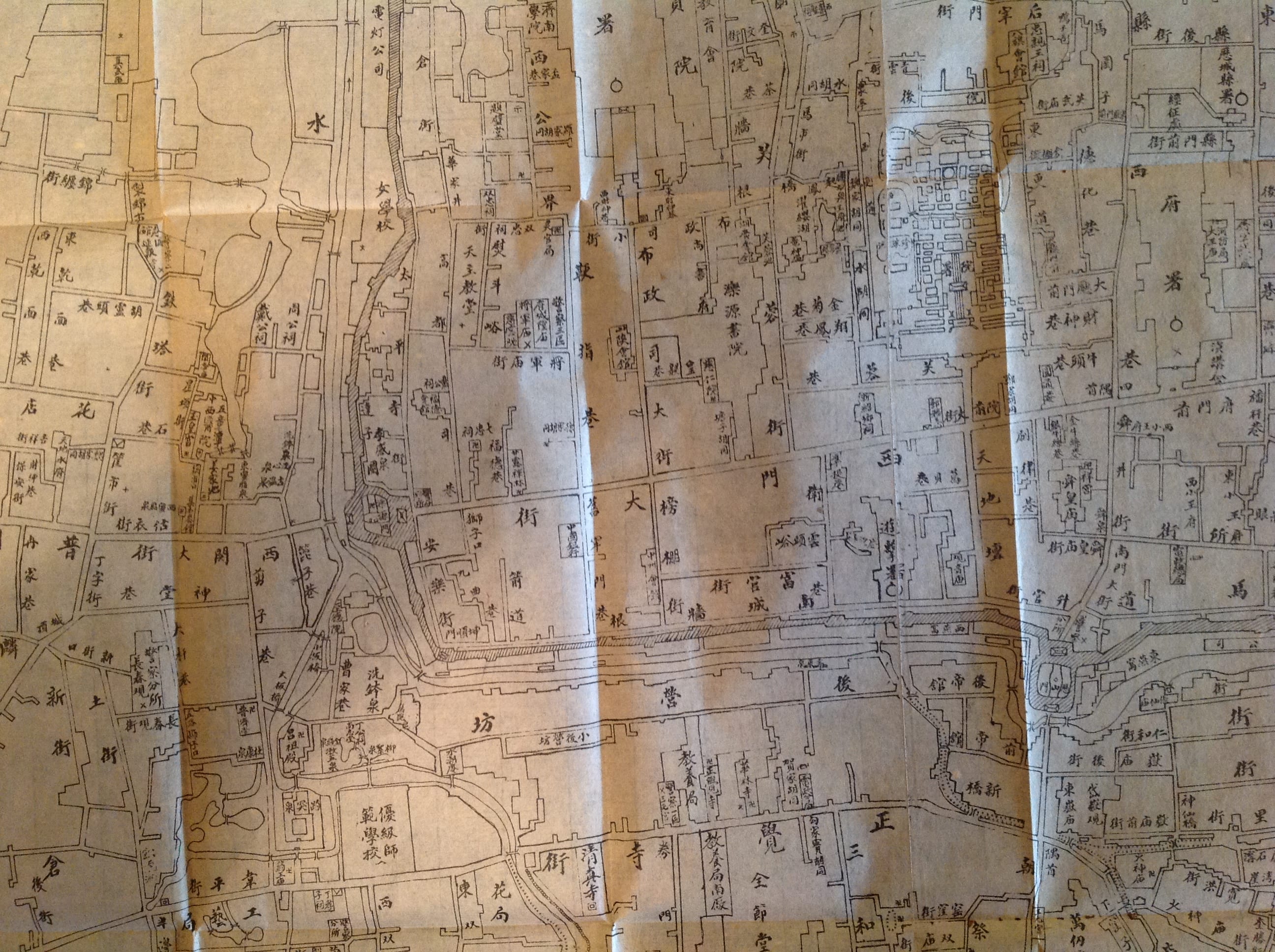

But the digitized versions don’t have everything. For example, the 1926 Licheng County Gazetteer includes a very detailed and useful fold-out map that is not included in the electronic database. Without having looked at the paper version, I never would have suspected that, since generally maps are included in the digitized copies. This is a small example of historians’ concerns about what gets left out when archives are produced and reproduced.

Southwest corner of Jinan’s old walled city from map in 1926 Licheng County Gazetteer

Archival research, then, is an exercise in not only reading what is there but wondering what is not, why it’s not, and where it might be found. This is one of the reasons completing a history dissertation takes so much time. Despite our best efforts to identify and delimit our archives, the borders are always fuzzy. While digitization has generally made access to archival materials easier, it has only raised further questions about how archives are made, how we use them, and how analog and digital sources should be checked against each other.

2 responses