Maintaining a degree of detachment from one’s object of study is an essential part of being an academic. For historians, that means that while our personal experiences and beliefs undoubtedly shape how and why we go about our research, the things that we study and the materials we use to study them are necessarily external to ourselves. (E.g. there’s a clear distinction between a memoir and a historical biography.) As I discussed a couple posts ago, though, that doesn’t mean that we can ignore questions about where the sources we use for historical research come from and how they got into whatever archive we are using. In this post I want to reflect on the role that I – as a PhD student in history – play in constructing and augmenting my archives.

One of the threads in my dissertation is an examination of the physical construction of urban space and visual representations of it. In particular, I am interested in how some of Jinan’s famous sites, two of which were outside the old walled city, were used to orient the city’s geography. One of these sites is Thousand Buddha Mountain (千佛山, also known as Li Mountain). There are many interesting things about this site, but one of the questions that has nagged at me is whether this mountain, located to the south of the city, might have shaped visual representations of the city itself.

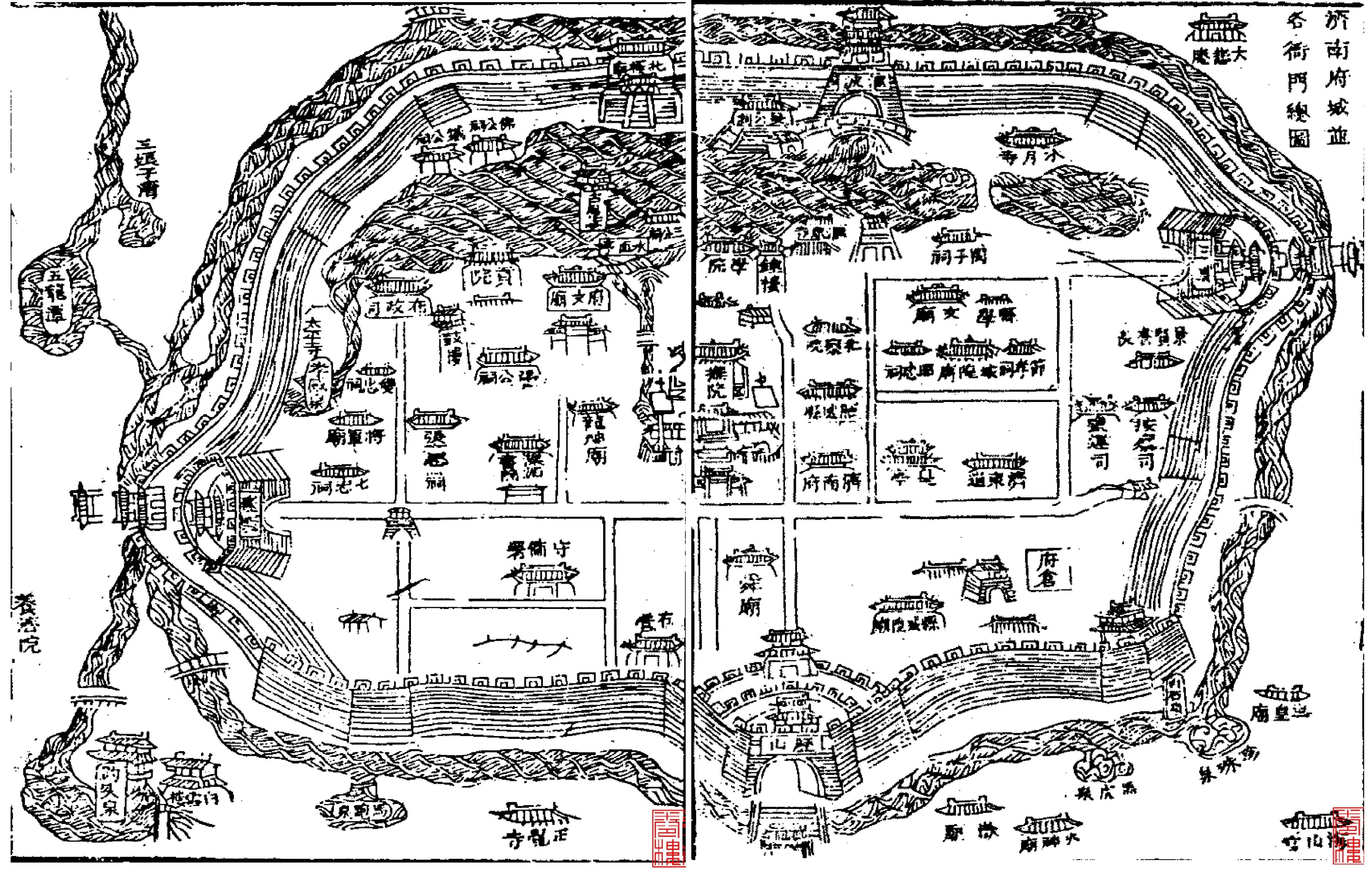

I started thinking about this question when I was looking at maps of Jinan from old gazetteers. I noticed that the maps consistently depicted Jinan as if viewed from the south and looking down on the city. This is apparent from the depiction of the city walls – while to the south the outside face of the wall is visible, the inside face is shown in all other directions. The result in several cases is an unnatural warping of the southwest and southeast corners of the wall, which suggests that the perspective from the south was not simply an accident.

Map of Jinan from the 1840 Jinan Prefecture Gazetteer

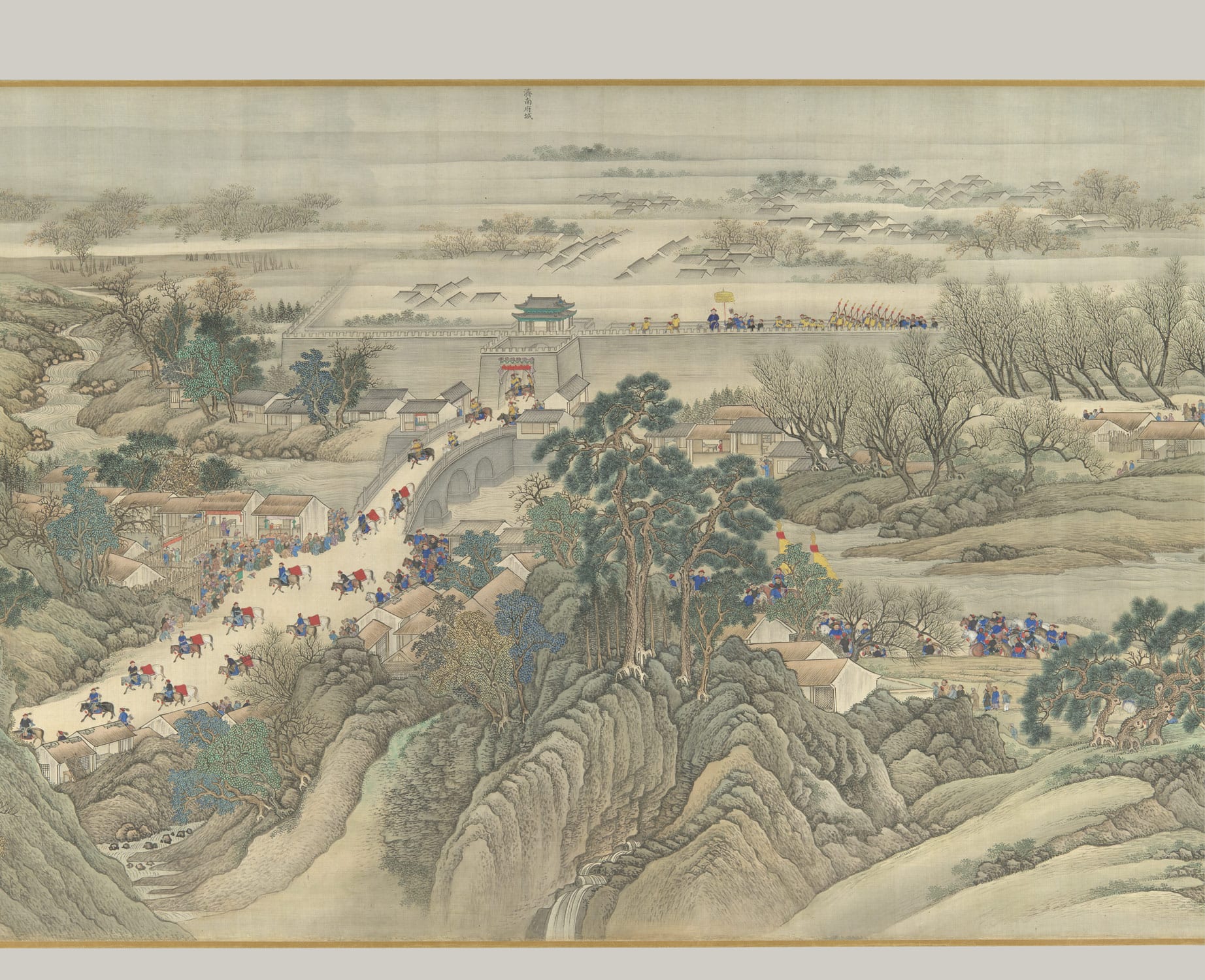

My curiosity was further peaked when I saw a painting of one of the Kangxi Emperor’s tours that depicted the emperor’s retinue passing through the city on his way to Mt. Tai. Again the perspective was from the south, as if one were standing at the top of Thousand Buddha Mountain. One of the reasons this was interesting was that at the top of the mountain is a shrine to the mythological sage king Shun, meaning that these depictions of the city – consciously or not – effectively reproduce the view from his shrine (as if his image were looking down on the city).

The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Tour, Scroll Three: Jinan to Mount Tai, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Given this interest, one of the things I was really looking forward to when I went to Jinan was climbing Thousand Buddha Mountain for myself to see what things looked like in person. It was important to me to take some photographs as well, despite my distinctly amateurish skills and equipment, both for my own purposes and to share with my friends (and now blog readers).

A lot about Jinan has changed in the last few centuries, but not the poor visibility.

My photograph, preserved on my hard drive, Facebook, and now WordPress, is obviously of a different vintage from the two images preceding it in this post. But it would be disingenuous of me at this point to pass off my role as simply a historian analyzing materials that have been produced and cataloged by someone else. In other words, I am not just a consumer of primary sources, but also a producer.

I don’t think this is necessarily an exception to what historians do. While we certainly don’t think of ourselves as mainly producers or compilers of sources, that is consistently at least an incidental part of much of the research we do. I think you would be hard-pressed to find a historian who has not created a private archive in some form in the course of their research.

There are two contexts where this role of historians as active contributors to archives becomes more explicit. The first is in cases where historians work in museums and institutions where their skills and experience curating primary materials come to the fore. The other is through digital platforms that allow for the dissemination of collected materials. This blog post is a small-scale example. A much larger one is Everyday Life in Mao’s China, an online collection of images from Maoist China curated by Covell Meyskens, a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, recently interviewed by The New York Times.

I suppose it is possible for historians to take a kind of purist stance when it comes to the question, to try to bury the ways in which we produce and curate sources beneath our scholarly analysis. I do, think, though, that it is more productive to be transparent about the ‘I’ in our archives. First, it allows us to speak more accurately and openly about what being a historian entails, which itself has a variety of benefits. Further, it puts us in a position to participate in conversations about the variety of sources that people produce on a day-to-day basis, be they Facebook photos or blog posts, and to share how historians view these practices based not only on abstract theorization but also practical experience.