Believe it or not, my time in Jinan is running down. I’ve decided to use my next few posts to write about three places that have been integral to my encounter with the city. I’ll focus on the people who inhabit and traverse them and the intersection between these slices of urban space, Jinan as a whole, global issues, and my ostensibly obscure (sike) dissertation research. My first post was about Baihua Park.

As I have written about before, one of my main research sites in Jinan is the Jinan Municipal Library. The library itself is a splendid facility, and the rare books and local documents reading room where I work is comfortable and handsomely decorated. The location of this library is, however, less than ideal – about a thirty minute drive west of the center of the city and even farther from our apartment on the east side.

One would think that such an impressive establishment would be found at the heart of the city for local people and occasional foreign visitors to enjoy. Instead, it forms one-third of a triumvirate of cultural institutions – along with a performance center and an art museum – around which the western outskirts of the city are sprouting up. The best way to get out there is to take a cab from closer to the city center. There are buses, but from our apartment the commute by public transit would take about an hour and a half each way. Due to the obstacle posed by the city’s underground aquifer, Jinan still does not have a subway, although one is supposed to open in the next couple of years. To get to the library, then, I use a hybrid of public transit and ride-sharing.

From left to right: art museum, library, performing arts center, apartment buildings

My car rides between the center of the city and the library have given me time to observe and reflect on the westward expansion of the city, which is both a very old and strikingly recent phenomenon. In the 1860’s the area around Jinan was repeatedly ravaged by a group of rebels called the Nian. The walled city itself was relatively safe, but the urbanized areas outside the walls required extra protection. In response, a series of earthworks were constructed around the city. A couple years later these were replaced with a stone wall. Along with areas that were already effectively part of the city, the new wall enclosed some relatively empty – but now protected – spaces that were attractive to people fleeing rebellions and natural disasters.

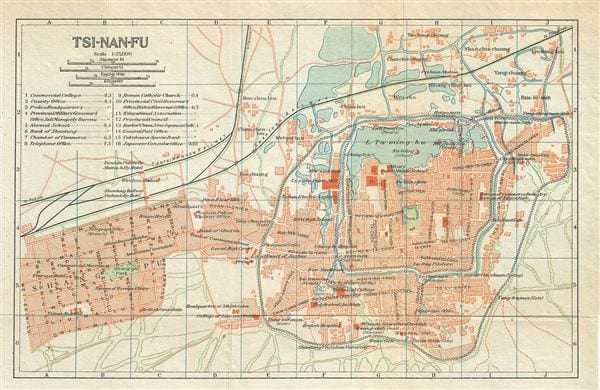

The formal expansion of the city continued with the opening of a commercial district (shangbu) to the west of the city in 1904. The commercial district was a preemptive measure to deal with growing foreign interest in Jinan as it became the crossroads of two important railway lines – one stabbing inland from the German colony of Qingdao on the coast and the other running from Tianjin to Shanghai. The idea was to open the city to all foreign merchants on Chinese terms in order to prevent one foreign power (in this case the Germans) from attaining dominance. In time, the commercial district and the railroad lines that met just north of it would exert tremendous influence on the city’s development.

A 1924 map of Jinan showing the two layers of walls, the commercial district, and the railway lines

Jinan’s newest railway station is also in the western outskirts of the city. As I learned the hard way – when I accidentally went to the wrong station once – this is where you board high-speed trains that will take you to north to Beijing or south to Shanghai. If you’re traveling to China, I recommend you try these trains – almost just for the experience. It’s worth it to be reminded that in some ways China has already surpassed the U.S. by some distance.

The history of trains – and Jinan’s connection to the rest of China and even the world – is bound up with the city’s westward expansion. From this perspective, early twenty-first century Jinan seems not so different from its early twentieth-century incarnation. What is different, though, is that the city has now expanded far enough to truly necessitate a new form of transportation: cars.

Obviously, automobiles aren’t a brand-new thing in Jinan or elsewhere. But the number of drivers on China’s streets has spiked dramatically in recent years. Between 2011 and 2015 the number of registered drivers increased from 174 million to 280 million. This is quite a nuisance in the downtown areas of Jinan that really were not designed for so many cars and where the streets are already congested with a toxic mix of pedestrians, bicycles, mopeds, etc. On the highway leading out to the train station and library, though, you almost feel like you’re driving into the future.

Sure, there are some traffic jams during rush hour, but it’s still so much faster and more comfortable than taking the off-highway bus. The passenger cars in China (excluding taxis) are also, on average, significantly newer than what you see on the streets in the U.S. When my drivers ask me questions like how much cars in the U.S. cost, I always stumble over the problem that I don’t pay much attention to the price of brand new cars because buying used cars is so popular.

The cars aren’t the only thing that’s new. Rows of newly built and under-construction apartment high-rises stretch along the highway. I find these unsettling, though. The buildings are too similar, too large. I rack my brain trying to imagine how many people it would take to fill them. I think about how many cars these people will need to travel into the city. The traffic jams. The pollution.

Since the early twentieth century, the western part of Jinan has served an important symbolic and functional role linking the city to a brighter future. Heading out there today, though, I sense the country is headed less toward the promised land of Xi Jinping’s “China dream” than a purgatory of late modernity. The promise is enticing – more space, shiny new buildings, higher standards of living, etc. But the costs discolor the dream like the gray lower stratum of the atmosphere that hugs the city’s skyline, spoiling the clear blue skies above.

I rarely see other foreigners on my trips to Jinan West. Nevertheless, to me, this part of the city is not a secluded corner of China. Rather, it continues to be a window to the world outside: a world where progress seems equally inevitable and unsustainable.

One response