“What is Happening?”: Language and Sound in Jaap Blonk’s “What the President Will Say and Do!!”

“What is Happening?”: Language and Sound in Jaap Blonk’s “What the President Will Say and Do!!”

Cecily Chen

At the beginning of his 2004 performance “What the President Will Say and Do!!” Jaap Blonk introduces the piece as “a short meditation” on Madeline Gins’ 1984 book of the same name. In contrast to his mild-mannered and modest preface, the performance itself is cutting and brutal. If the piece is indeed a “meditation,” it is by no means a restful one. Blonk first repeats the title phrase “What the President Will Say and Do” in an official, announcer-like voice, but after his sixth repetition, each time the phrase is uttered, it disintegrates bit by bit, until eventually the performance changes completely from a clearly enunciated sentence to a series of strangled grunts and gasps. Language and syntax are not only broken down, they are violently stripped away from the speaker, leaving behind only a struggle for words and breath that is never quite fulfilled, if not abruptly cut short. But who, exactly, is this speaker? Is it the artist? The titular “president”? Someone else completely? Who is speaking, and who fails to speak? Who is Blonk channeling, as he moves from articulation to disarticulation, from language to mere sound?

Taking this tension between semantics and phonetics as a point of departure, I want to foreground Blonk’s experimental poetic practice and parse its various political dimensions. My reflections on this performance will be divided in three parts. First, I will provide a brief gloss of Jean-François Lyotard’s 1992 essay “Obedience,” which posits a direct relationship between listening and submission, and use it as a theoretical frame through which I examine Blonk’s avant-garde—or, in Lyotard’s terms, “postmodern”—poetics. Second, I will situate Blonk’s piece within the broader context of Dada sound poetry, which the artist himself frequently cites as his lineage and influence. Further, comparing Blonk’s performance with the original Madeline Gins book, I am interested in what is lost and what is gained, both aesthetically and politically, through Blonk’s Dadaist maneuvers. Lastly, I will end with a more extended analysis on the speaker—or its multiple speakers, its polyphony—of the performance, and invite thoughts for further discussion.

In “Obedience,” Lyotard argues that there is a close link between the act of listening and a position of subservience, and that “new technologies” of avant-garde practices draw the listener’s attention to this subservience. Noting that tucked within the French word obédience is the Latin word audire—that is, to hear—Lyotard views submission as integral to listening. For Lyotard, to hear something, to lend one’s ear, necessitates that the listener accepts and acquiesces to the conditions that give rise to a specific sound or tone. The transmission of sound is not only an instance of communication, it engenders a relation of power that is often naturalized, internalized, undisputed. By “liberating” sound from previous schemas of composition, however, avant-garde experiments extract listeners from their familiar sound-environments, and thus alert them to their obedience to what they hear. Lyotard writes,

A procedure of this sort [i.e. postmodern art] modifies a great deal the sensitivity of the ear (I mean the mind) to rhythm. Put bluntly, you can’t dance to this music. The regulating metronome disappears. Its regular movement is replaced by the continuous race of the chronometer, which is started and stopped arbitrarily (the break of causality)… The rhythm of the sound is not within the “natural” or “cultural” rhythmic capacities of the body. The body’s command over ‘its’ space (or vice versa) by means of movements is thereby unsettled. Rhythm is referred solely to immobile listening, which can then be called interior listening… [T]his non-measure rhythm demands that one wait: what is happening?[i]

Breaking from “the regulating metronome,” avant-gardist compositions start and stop arbitrarily, obstructing any “natural” or “cultural” responses the listener may have, such as swaying to the rhythm of the music. Instead, the listener is left fixed, immobilized, unsure what they are supposed to do, how they should react—unsure, even, about “what is happening.” The listener thus comes into awareness of their passivity to sound. In asking the question “What is happening?” the listener is in fact asking, “What am I hearing? And why am I listening to it?”

Although Lyotard focuses on the friction between music and noise, his analysis could be extended to Blonk’s piece, which plays with conventions not strictly of music but also of speech. Throughout Blonk’s performance, the metronome of language—grammar and syntax—rapidly deteriorate, collapsing semantic meaning into garbled, unintelligible cries, into phonetic sound. To listen to Blonk’s piece is to sit with it and wonder, “What is happening?” A 2008 roundtable discussion with Al Filreis, Tracie Morris, Kenneth Goldsmith, and Joshua Schuster speaks to the multivalent cacophony of Blonk’s performance, which is as unsettling as it is provocative.[ii] Between the panelists, Morris hears patriotic marching at the beginning of the piece and chicken-like clucking toward the end, whereas Schuster makes a connection between Blonk’s gags and the then-recent revelation of the practice of waterboarding and torture at Guantanamo Bay, bringing to the surface the political stakes of the question “What is happening?” At the same time that Blonk’s piece brings about a web of associations—with nationalism, irony, and state-sanctioned violence—it renders its audience immobile, uncomfortable, hesitant to react. After all, any natural response we might have to an act of performance—such as to sit back, to smile, or to applaud—now appears malapropos. As Blonk’s voice becomes increasingly constricted and frantic, as if being strangled or drowned, he subjects the audience to a scene of extreme injury as its witness. Listening, then, implies not only obedience but complicity.

Emptied of semantic meaning, sound still reverberates with signification. To that end, it is important to recognize Blonk’s affinity with the tradition of Dada sound poetry, which insists that sound carries psychological and political import. Emerging in the wake of the First World War, Dada sound poetry seeks to make sense of a state of affairs that seems to escape logic and rationality, and turns to nonsense and noise to develop a new vocabulary that befits a world at the edge of wholesale destruction. Blonk’s piece shares this impulse to lay bare the senselessness in the violence in the world—as Tracie Morris notes at the roundtable discussion, for instance, the performance could be interpreted as a commentary on the vacuousness of electoral politics. There is also, however, an affective dimension to the practice of Dada, one which is expressly concerned with engaging with its listener and activating them into joining the speaker in a reflection on absurdist, anarchic nonsense. In his analysis of the history of sound poetry, Tobias Wilke argues that the “pure sounds” of Dadaist poetics are “affectively charged” and “trigger… an effect of articulatory mimicry on the part of the recipients, thereby re-inducing via bodily motions e-motional conditions similar, if not identical, to the ones out of which they emerged.”[iii] Recalling watching Blonk performing the piece in person, Kenneth Goldsmith breathlessly exclaims that it is “unbelievable” to see a man of Blonk’s rather tall stature “hold his breath and gag” and “turn purple,” a sight both impressive and doubtlessly chilling. Yet even without the visuals available, the affective richness of the piece remains in its sound, if not multiplied by it—without the physical presence of other listeners, without seeing Blonk standing on a podium, it is even more difficult to separate performance from genuine pain, theater from reality. The pure sound of Blonk’s gagging solicits from us an emotional response that exposes our passivity. What are we hearing? Who are we hearing? And why are we simply standing by?

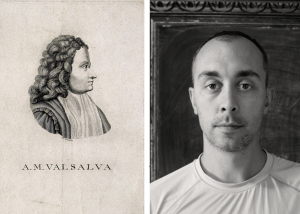

Eroding language as a sign system, Blonk’s piece emphasizes the capacious ability of sound to convey multiple voices at once and to proliferate new possibilities of meaning-making. Compare the form of Blonk’s performance with Madeline Gins’ 1987 book of poetry, which Blonk cites as the inspiration for his piece. Gins’ book opens with a section called “President Poems (Before)” which compositionally rhyme with Blonk’s interpretation of it: both are, to borrow Goldsmith’s observation, playing with the idea of a permutation poem, rearranging the same words and uncovering differences in repetition.[iv] As we see here, Gins appropriates the well-known nursery rhyme “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” as “original poems” which she writes as specific American presidents, parodying notions of creativity, originality, and the vapidness of political theater in one breath—with each passing presidency, the lullaby becomes only further truncated, mutilated. Similarly, Blonk stays with one piece of text and gradually unravels it; yet, in contrast to Gins, he never elaborates what exactly the president will say, not even in the form of a nursery rhyme, nor does he specify which president it is that he is speaking of. The form of the piece is its content, polemicizing not only the empty promises politicians make to their constituency, but the political establishment at large which normalizes these forms of speech.

Fig 2. “An Original Poem by Richard M. Nixon” by Madeline Gins, in What the President Will Say and Do!! (1984)

Where Gins satirizes those in power by taking on their names as personae, Blonk’s performance is polyphonic. There is a reason that Morris hears chicken noises while Schuster hears waterboarding in the piece: it is because it is all there, in cacophonous resonance. Although the piece begins with an official tone of voice that speaks to power and authority, the spoilage of its initial articulateness is suggestive of the voices of those disempowered and disenfranchised: those subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques” and chokeholds, those whose voices are quietly struck from record, but who still scream for their survival. If, as Lyotard argues, listening necessitates a position of obedience, then, conversely, to vocalize and intone carry the potential of gathering agency. In this sense, we might identify Blonk’s piece as a radically subversive gesture that calls for an insurgent politics: as he struggles for breath and gags and gasps, he also drowns out the hollow eloquence of the ruling class with the voices of the subjugated. He unsettles us, the audience, with the visceral intensity of his choked off words and muffled screams, leaving unspoken questions of politics, agency, and collective action ringing in our minds. The question which Lyotard poses for us—What is happening?—therefore takes on dual signification: what is happening in this performance, and what is happening in a world that prompts such a performance?

[i] Jean-François Lyotard, “Obedience” in The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1991) 165-182, 169.

[ii] Al Filreis, “How to Hold Your Breath and Gag: Jaap Blonk, ‘What the President Will Say and Do’” PoemTalk #6 (May 4, 2008) https://jacket2.org/podcasts/hold-your-breath-and-gag-poemtalk-6

[iii] Tobias Wilke, “Da-da: ‘Articulatory Gestures’ and the Emergence of Sound Poetry” MLN Vol. 128, No. 3, German Issue (April 2013), 639-668, 653. l

[iv] Madeline Gins, What the President Will Say and Do!! (Barrytown, NY: Station Hill Press, 1984 [Ubu Editions: 2002])

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.