By Rob Mitchum // November 29, 2012

Depending on your perspective, Twitter is either a colossal waste of time or an addictive tool that has changed the way people interact online. But there’s no arguing that the service generates a ton of data, with roughly half a billion tweets posted around the world each day. As with any enormous data set, there are likely valuable signals to be captured from within that massive noise…with the right tools. In an award-winning master’s thesis, Computation Institute scientist Mattias Lidman set out to see if he could use the avalanche of daily tweets to predict the future winners and losers of reality shows and stock markets.

Financial analysts have long looked for an information advantage in playing the market, a way of knowing and acting upon important news before other investors. Logically, people have tried to use internet activity to make predictions about future market trends, including a paper last year that looked at web search terms and trading volumes. But Twitter offers a new promising data mine from which to extract predictions, due both to its global popularity and its ephemeral nature. While writing a news article or a blog post (usually) requires both time and a computer, Twitter’s portability and brevity enables more frequent, train-of-thought use.

“That’s what makes it such an excellent source for doing a project of this type,” said Lidman, a programmer with Globus Online. “People just blurt out whatever happens to be on their mind at the moment, and you get a very direct measure of what people are up to and thinking about, and their opinions for just that brief snapshot in time.”

Since Twitter remains relatively new, only a few other studies before Lidman’s have attempted to reveal its prophetic powers. One rated how closely positive or negative mentions of politicians tracked with approval ratings. Another tested whether mentions of an upcoming movie before its release predicts its box office performance. And one paper looked at the relationship between Twitter “mood” and stock market dynamics, finding that the frequency of “calm” tweets could predict the movement of the Dow Jones Industrial Average 2 to 5 days later. But Lidman was skeptical of this previous study, pointing out that the analysis took into account every tweet posted to the service, not just those specifically discussing financial markets.

“To believe these results you would have to believe that teenagers tweeting about Justin Bieber has some effect on the stock market several days into the future,” Lidman said.

For his master’s thesis (completed as a student at Umeå University), Lidman also constructed a “sentiment analyzer” that could automatically detect whether a tweet was positive or negative in tone using words and emoticons. However, he decided to apply that method only to tweets discussing a particular target subject, rather than to the full tweet torrent.

Before wading into the complex waters of the stock market, Lidman attempted to predict a lower-stakes competition: the Swedish pop-star show Idol. Just like American Idol, Swedish Idol viewers vote each week for the contestant that they want to stay on the show, and then the two that received the lowest votes are forced to battle it out in a second round of elimination voting. By monitoring the number of positive tweets for each contestant, Lidman was able to predict 8 of the 11 contestants that fell into the bottom two over the show’s 2010 season.

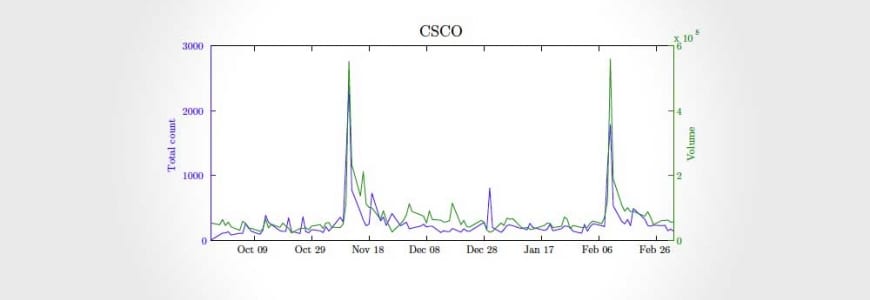

The NASDAQ stock market presented a far more complex challenge, with thousands of “contestants,” constantly fluctuating data and a number of different measures of success. Lidman choose a small pool of stocks to track – largely tech companies such as Apple, Amazon, and Google – and only used tweets that mentioned their stock symbol name (such as AAPL, AMZN, or GOOG). That was still 9 million tweets over a nearly six-month period that could be tested for correlation with different measures of stock performance such as opening price, closing price, and volume of shares traded.

For many of the companies analyzed, Lidman found clear correlations between the flow of tweets mentioning their stock symbol and the performance of its stock. But these correlations fell into three groups: times when the Twitter spike preceded the stock movement, times when the stock price or volume changed before the Twitter swing, and times where they coincided. For an investor looking to act before the market moved, only the first group of correlations would be of interest.

So Lidman refined his method to isolate only those Twitter swings expected to predict a market movement, based on preceding activity. While some of his results suggested that Twitter fluctuations could predict market movement as much as two weeks into the future, Lidman wrote that those longer time frames may be statistical anomalies and “slightly magical” as far as hypotheses go. More reasonable was an expectation that his method could use Twitter to predict a market swing within the next day or two, he said.

For his work, Lidman received the Swedish Engineers award for best MSc thesis, including a prize of 25,000 Swedish kronor (about $3,770). But Lidman said he won’t be reinvesting that money into Twitter-guided stock purchases, and that the method alone probably wouldn’t work well enough to lead an investor to easy, automated fortune.

“It could be used as a tool, among others, to give an early warning that something is happening,” Lidman said. “You can have a red light start flashing at a trader’s desk and bring up a sampling of the tweets that triggered that light to come on. But at the end of the day you need a human to actually go through the material and determine if there’s something you need to act on or not.”