In an image I’ve looked at hundreds of times (Wegner 2009, p. 481, fig. 15; Wegner 2010, p. 131, fig. 7.5), an ancient Egyptian woman is giving birth, attended by three women (fig. 1). One attendant, the most important for our purposes, holds a curved object made from the tusk of a hippopotamus. The tusk is carved with fearsome figures of the Egyptian wilds like baboons, lions, and serpents. With it, the woman traces a circle in the sand around the laboring mother.

(Wegner 2009, fig. p. 481, fig. 15, reproduced with permission of the author).

This scene, first published jointly by Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania in Archaism and Innovation, has become one of the most familiar ways scholars and museums imagine how carved tusks were used.

It is a powerful, evocative image. But what if it is not quite the whole story of the objects it portrays?

The Problem with “Magic Wands”

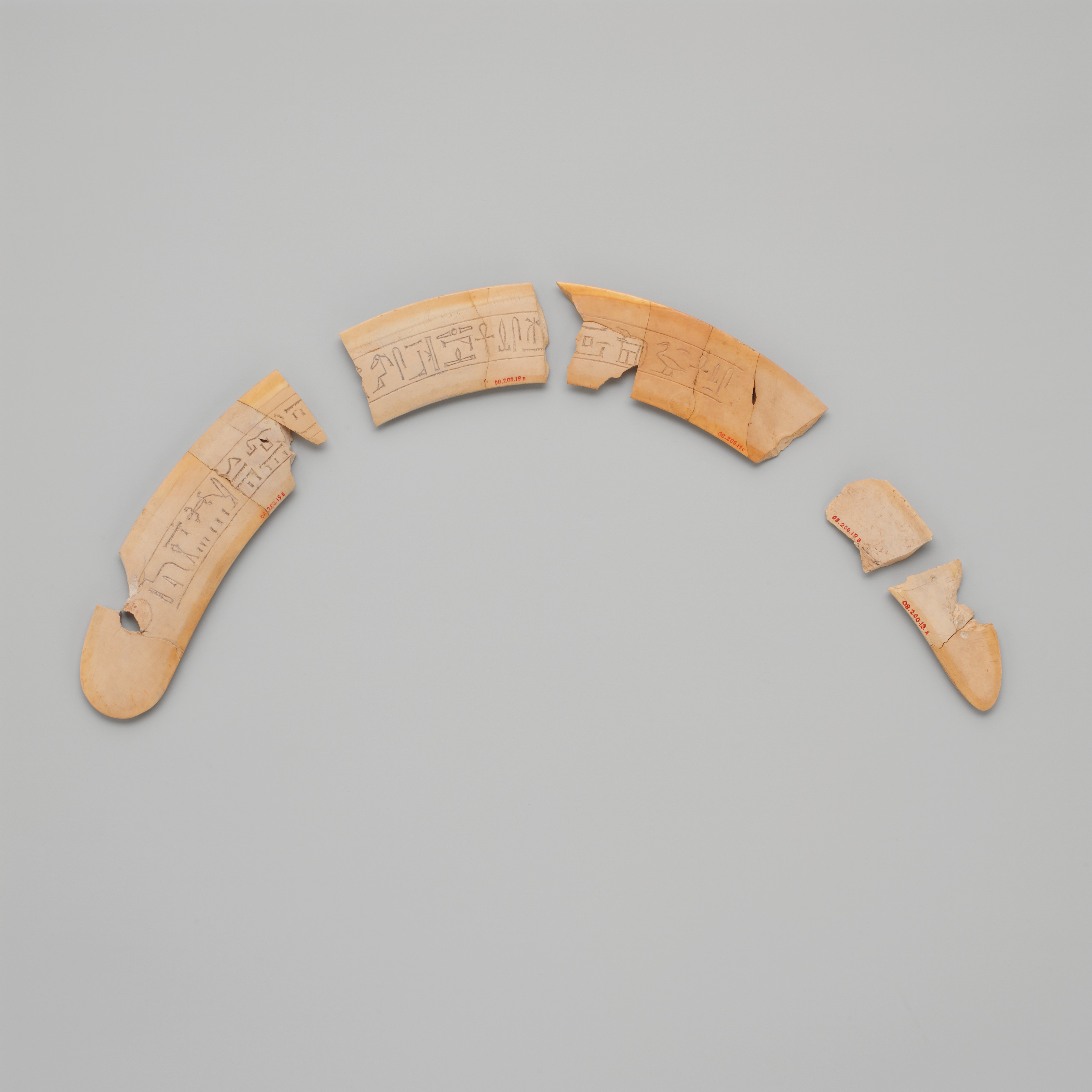

For over a century, Egyptologists have studied carved ivory objects made from hippopotamus tusks (fig. 2), often referred to as “wands,” “knives,” or “apotropaia.” About 175 examples survive today, dating from the First Intermediate Period through the Middle Kingdom (c. 2150–1650 BCE). Most were found in tombs, as far north as Lisht and as far south as Aswan. Catalogs of the corpus have been published by Altenmüller 1965, Altenmüller 2021, and Quirke 2016.

(ISACM E10788, D. 17954 © Courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago).

Their craftsmanship is remarkable. The natural curve of the tusk was preserved, forming a crescent shape with a broad, rounded end that tapers to a point. Along the surface, intricate carvings show protective creatures: baboons, crocodiles, lions, serpents, and hybrid deific beings. Many of these entities have been cataloged in the DemonBase as part of the DemonThings project. Some tusks even carry inscriptions in which the figures themselves speak as “protectors” (sꜢ.w), promising to guard their owners, often women of high status and sometimes their children (fig. 3).

But the names we have given these objects do more than describe, they influence how we imagine them in action. Wands are waved, knives cut, and “apotropaia” evokes Greek concepts of averting evil. Without a foundation in evidence from the objects, this vocabulary also echoes Victorian-era ideas about Egypt as a cradle of occult knowledge, on full display in such artwork as John William Waterhouse’s painting The Magic Circle (fig. 4). While these terms are useful, they can also carry assumptions that the evidence itself does not always confirm.

The most popular theory, on display in Wegner’s reconstruction, is that tusks were used to scrape protective circles around vulnerable people, especially mothers and children. This idea draws on the well-attested Egyptian practice of encircling (pẖr) to create safety and sacred space (see Ritner 1993 [2008] and Lightbody 2020). It is compelling, and it fits neatly into broader understandings of Egyptian ritual.

But when we look closely at the tusks themselves, the story becomes more complicated.

Evidence from the Objects

As part of my research on these objects, I examined 59 tusks from archaeological excavations—roughly a third of the known corpus—in order to see whether the objects bore physical traces of the circle-drawing theory.

If tusks were meant to be dragged through sand or soil to create protective shapes, we would expect to see consistent wear: smoothing, scraping, or chipping at the tips. But out of 59 examples, only 6 showed signs of wear at the pointed end, far too few to suggest a widespread, repeated practice.

What I did find was something different. Nearly 85% of the tusks were broken across their width and snapped into two or three segments. These breaks were not haphazard damage from time in the ground; they followed strikingly similar patterns. Some tusks had even been pierced with holes, or repurposed into entirely different objects, like the handle of a knife.

In other words, the tusks seem to have had longer, more complex “biographies” than a single act of circle-drawing could explain.

Breaking as Ritual

The breakage patterns echo a broader Middle Kingdom practice. In a cache found in a tomb dug into the Ramesseum precinct (Quibell 1898), for example, almost every object—from figurines to tusks—was intentionally damaged (fig. 6). Figurines were broken at the ankles or pelvis, ivory clappers snapped below the wrists, tusks fractured into thirds. Scholars such as Gianluca Miniaci have shown that this kind of deliberate breakage was not careless destruction, but ritualized action (Miniaci 2020; Miniaci 2023). In this light, the snapping of tusks may not signal an end, but rather a completion: an act of transformation that allowed the carved tusks to take on a different role in the afterlife.

This interpretation finds an intriguing parallel in the experimental work of Kasia Szpakowska and Richard Johnston (Szpakowska and Johnston 2016). Their study of cobra-shaped clay figurines found in fragments across Egypt and the Levant sought to determine whether “clean” breaks necessarily indicated intentional ritual smashing. By replicating and breaking forty modern clay cobras, they demonstrated that accidental impacts can also produce surprisingly neat fractures, complicating long-held assumptions that such breaks must signal ritual killing.

Their results underscore how careful we must be when reading intentionality into patterns of fragmentation. While some tusk and figurine breaks may indeed represent deliberate ritual “killing,” others could stem from accidents, post-depositional processes, or structural weaknesses.

Rethinking the Evidence

These findings encourage us to revisit familiar assumptions. The circle-drawing theory remains possible, but the tusks themselves do not decisively support it. What the evidence does show is systematic breakage, occasional repurposing, and inscriptions that clearly affirm their protective purpose.

It may be that “killing” or breaking the objects was itself part of activating or deactivating their power. The few tusks that do show tip wear could represent occasional or alternate uses, but not the primary one.

Rather than replacing one uncertain conclusion with another, I see this work as an invitation to keep asking questions. What did it mean to ritually “kill” an object in Middle Kingdom Egypt? How might this practice relate to the “mutilated hieroglyphs” we find in tombs? And how might the ivory itself, drawn from the formidable hippopotamus, have shaped the tusks’ symbolic power?

Looking Ahead

Theories like circle-drawing are powerful because they make sense to us. They draw together ritual practice, text, and image into a vivid narrative. But even the most persuasive interpretations need to be tested against the objects themselves. Sometimes the material record complicates the picture, suggesting new possibilities.

In the case of the tusks, that picture may be more varied, more fragmentary, and more fascinating than a single circle in the sand.

This research, first developed for my MA thesis at the University of Chicago, is work I intend to publish more formally. For now, I hope it demonstrates the value of slowing down, looking closely, and allowing the objects to guide us, even when they lead us somewhere unexpected.

Cite:

Beth Wang. “Rethinking Ancient Egyptian ‘Magic Wands’: What the Objects Tell Us.” Daily Demon. Demon Things: Ancient Egyptian Demonology. October 2, 2025. https://voices.uchicago.edu/demonthings/2025/10/02/rethinking-ancient-egyptian-magic-wands-what-the-objects-tell-us-by-beth-wang/