by Maggie Zhang

Graduate student in the Committee on Microbiology

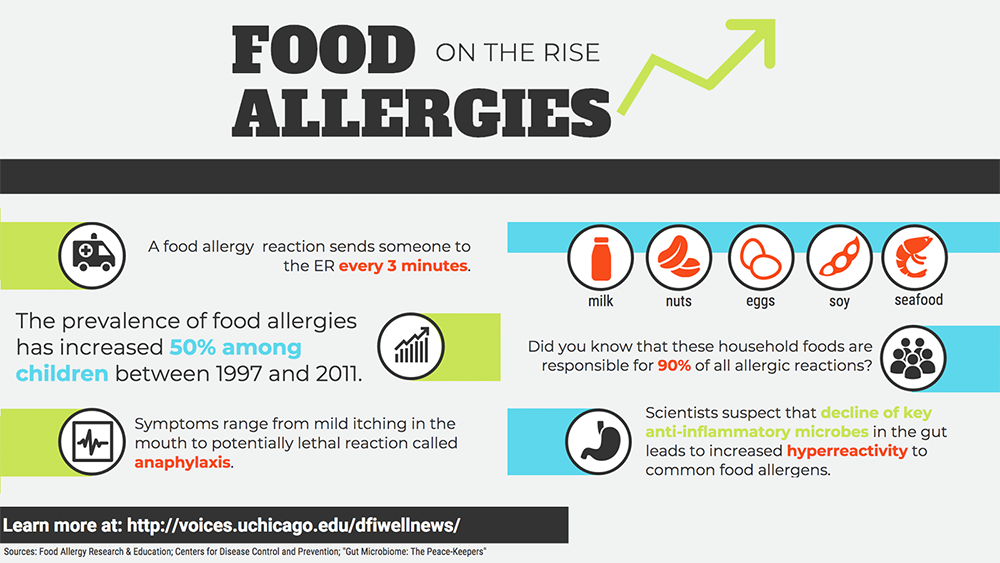

Food allergies constitute a major public health concern. For an estimated 15 million Americans, exposure to common foods such as peanuts and milk causes negative, even deadly, immune responses. In recent years, food allergy rates among children have risen sharply, increasing approximately 50 percent between 1997 and 2011.

Why is the problem growing?

Let’s go back to the nineteenth century, when the findings of Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and many others were converging on an essential function of the human body: immunity. The immune system was so named because it seemed to “exempt” the body from attack by microorganisms.

Given that microbial infection was thought to be the primary cause of immune reactions, it seems counterintuitive that people today—more free from infectious disease than ever—would be so heavily crippled by inflammation, the quintessential immune response. But decades of research reveal that a hyper-reactive immune system underlies autoimmune and allergic diseases, leading to severe conditions such as anaphylaxis.

Anaphylaxis can be life-threatening. In the same way that a healthy immune system reacts robustly to the intrusion of foreign toxins and microbes, a hyper-reactive one can respond just as dramatically to certain foods.

Despite the increasing prevalence of food allergies, current treatment options are problematic. Searching for new solutions, scientists have turned to the gut microbiome, the teeming ecosystem of microscopic organisms occupying our gastrointestinal system.

For some 800 million years, we have been building mutually beneficial relationships with the microbes that dwell within our gut. But over the past few decades we have drastically altered the environment that they call home, thanks to widespread antibiotic administration, extreme sanitary practices, and especially a high-fat, low-fiber diet.

Our dietary choices affect the species of bacteria that live within us. Our microbes eat what we eat, taking a small cut of our food in exchange for synthesizing nutrients that we need but cannot make ourselves. Many bacteria ferment what we cannot digest, such as the soluble fibers in vegetables, fruits, grains, and legumes. As a byproduct, they produce anti-inflammatory molecules called short-chain fatty acids.

Bacteria known as Clostridia are star performers. Cathryn Nagler, PhD, and her team have pinpointed Clostridia as key peacekeepers in the gut microbiome. Using mice born and raised in a microbe-free environment, Nagler’s group has demonstrated that introducing Clostridia blocks sensitization to food allergens. The microbes foster an anti-inflammatory environment within the gut in multiple ways, promoting the secretion of mucus along the gastrointestinal lining and producing a short-chain fatty acid called butyrate, which nourishes cells in the colon. These help to create a protective barrier in the gut, which prevents allergens—like peanuts and milk—from encountering pro-inflammatory immune cells.

These findings might soon change how we treat allergies. Nagler has teamed up with Jeffrey Hubbell, PhD, of the University of Chicago’s Institute for Molecular Engineering, to launch the start-up ClostraBio in order to commercialize novel food allergy remedies. Their aim is to develop novel, targeted treatments to restore the protective barrier naturally provided by peacekeeper microbes.

For centuries, we have appreciated the protective functions of the immune system against microbial attack. We have memorialized the contributions of Pasteur and Lister in everyday words like pasteurization and Listerine®, concentrating on the harmful bacteria that we must eliminate to remain healthy.

But in fact, only about 2 percent of all microbes are pathogenic—the rest are neutral, beneficial, or even essential to our well-being. While there is no doubt that modern sanitary practices have reduced the scourge of infectious disease, we have come to understand that though “bad” microbes can cause disease, “good” bacteria can also prevent it.

Just as plants depend on microbes to extract vital nutrients from the soil, scientists now hypothesize that animals only achieved mobility when we learned to carry within our bodies the microbes necessary for our survival. Maybe it’s high time for us to appreciate the importance of our symbiotic pact with the microbes that helped make us who we are today.