By: Eva Kinnebrew

In 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population, in which he introduced what seemed like an impending catastrophe. Malthus had calculated the rate of population growth as well as the rate at which we increased agricultural output and found that within two centuries, the population and its food needs would exceed our ability to produce enough crops [[“Malthusian Theory of Population.” AAG. AAG Center for Global Geography Education. 18 September 2011. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://cgge.aag.org/PopulationandNaturalResources1e/CF_PopNatRes_Jan10/CF_PopNatRes_Jan108.html>]]. A food crisis, he wrote, seemed inevitable if we did not curve population growth.

Two centuries later, we have in several ways outsmarted Malthus’s model. For one, population growth has slowed (he predicted that the population would be 9 billion by 2000). More importantly and outstandingly, though, through agricultural advancements we have far surpassed Malthus’s predictions of food production. We currently produce more than enough food to feed everyone in our population [[“Frequently Asked Questions: Hunger.” World Food Programme. 2016. Web. 25 January 2016. <https://www.wfp.org/hunger/faqs>]][[Gimenez, Eric Holt. “We Already Grow Enough Good For 10 Billion People – and Still Can’t End Hunger.” Huffpost Taste. The Huffington Post. 02 May 2012. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-holt-gimenez/world-hunger_b_1463429.html>]]. On the surface, it seems as though we have dodged the bullet of the food crisis. Oddly enough, though, the world still looks a lot like Malthus predicted it would.

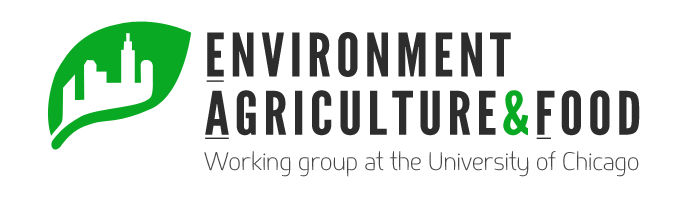

![Figure 1: A map of world hunger, compiled by the FAO, shows the prevalence of hunger throughout the world and especially in developing areas. Colors relate to the percentage of the population in that country that is affected by hunger [4]](https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/4/415/files/2016/02/Picture2.png)

Figure 1: A map of world hunger, compiled by the FAO, shows the prevalence of hunger throughout the world and especially in developing areas. Colors relate to the percentage of the population in that country that is affected by hunger [4]

Despite our slowed population growth and agricultural advancements, food insecurity is an all too pervasive problem in our society. One in nine people don’t consume enough energy to live an active and healthy life and an even larger percent suffer from malnutrition, often by micronutrient deficiencies [[“The FAO Hunger Map 2015.” The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/>]]. In addition, one in four children suffer from stunted growth as a result of undernourishment [[Onis, M, Blössner, M, and E Borghi. “Prevalence and trends of stunting among pre-school children, 1990 – 2020.” Public Health Nutrition (2012):15,142-8. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/publications/stunting1990_2020/en/>]]. Malnutrition is widespread. See the below map of world hunger, taken from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) [[“The FAO Hunger Map 2015.” The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/>]].

So what’s the catch? Why are families are still going hungry around the globe even though we produce enough food for our population? Where is all that food going? The word “produce” is key. While we may produce enough food to feed all 7.4 billion people (actually, we produce enough to feed 10 billion people), the path from farm to plate is often long and complicated [[Gimenez, Eric Holt. “We Already Grow Enough Good For 10 Billion People – and Still Can’t End Hunger.” Huffpost Taste. The Huffington Post. 02 May 2012. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-holt-gimenez/world-hunger_b_1463429.html>]].

Current reports estimate that as much as a third of the food produced worldwide (1.2 billion metric tons) is wasted every year, and there are several major explanations for this disparity between production and consumption [[Gustavsson, Jenny, et al. “Global food losses and food waste.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rom (2011).]] [[Parfitt, Julian, Mark Barthel, and Sarah Macnaughton. “Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050.”Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 365.1554 (2010): 3065-3081. Web. 25 January 2016.]]. Consumer waste (in other words, post-purchase food that spoils or otherwise goes uneaten) accounts for some of this, and is tightly linked with the issue of distribution. This issue should not be understated, and addressing it will be an important step towards reducing overall food waste and ensuring population health (see Raj Patel’s novel Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the Food System for an excellent account of this) [[“Stuffed and Starved.” Raj Patel. 27 October 2009. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://rajpatel.org/2009/10/27/stuffed-and-starved/>]]. The majority of food waste, though, occurs before even reaching consumers, which is extremely disconcerting. For this reason, I want to specifically focus on pre-consumer food waste.

Three main contributors to pre-consumption food waste are climate change, urbanization, and transitioning dietary preferences. Climate change has complicated agricultural systems by changing ecosystem food webs, altering chemical cycling that is vital to crop health and vitality, and causing unpredictable and often disastrous weather [[“Climate Change and Food Security: A Framework Document.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2008. Web. 25 January 2016. <ttp://www.fao.org/forestry/15538-079b31d45081fe9c3dbc6ff34de4807e4.pdf>]]. Pests and diseases, for example, have begun inhabiting new areas as a result of global warming. A study published in Nature in 2013 found that fungi and insects, many of which are crop parasites, are traveling towards the poles at a rate of up to 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) a year [[Barford, Eliot. ”Crop pests advancing with global warming.” Nature News. Nature. 01 September 2013. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://www.nature.com/news/crop-pests-advancing-with-global-warming-1.13644>]]. Farmers and their agricultural crops are unprepared for this attack, and as a result many crops are failing to mature or even make it off the vine.

![Figure 2: Phytopthora infestans, the same pathogen that caused the Irish potato famine, infects a tomato plant. This pathogen is still a concern in many countries [12]](https://bpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/4/415/files/2016/02/Picture3.png)

Figure 2: Phytopthora infestans, the same pathogen that caused the Irish potato famine, infects a tomato plant. This pathogen is still a concern in many countries [12]

Finally, dietary preference encourages food waste by creating a market for non-local foods and also shifting tastes away from starchy foods and towards more perishable items, like fruits and vegetables. Before colonization and ease of transport between geographically distant areas, humans consumed crops that they could cultivate locally. Now, however, we have access to a wealth of crops from all around the world. Mangos from Central America and mushrooms from Asia line our grocery stores and have become regulars in our diet. The globalization of food adds to food waste by, as mentioned, increasing transportation times, but also by overshadowing local foods. In the presence of exotic, attractive products, local crops may be neglected and thus left on the shelves.

Another interesting case involving dietary preference is the shift away from starchy foods, which is referred to as Bennett’s Law [[Parfitt, Julian, Mark Barthel, and Sarah Macnaughton. “Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050.”Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 365.1554 (2010): 3065-3081. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/365/1554/3065.short>.]] [[Cirera, Xavier, and Edoardo Masset. “Income distribution trends and future food demand.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 365.1554 (2010): 2821-2834. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/365/1554/2821>]]. This law, which was theorized by M.K. Bennett, a wheat researcher in the mid-nineteenth century, states that as consumers’ incomes increase, they move away from starchy foods and towards fruits and vegetables. Starchy foods have a much lower associated loss than fruits and vegetables. Thus, as countries get richer, they prefer more spoilage-vulnerable food and thus contribute more to food waste. This trend has been detected in current food markets [[Parfitt, Julian, Mark Barthel, and Sarah Macnaughton. “Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050.”Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 365.1554 (2010): 3065-3081. Web. 25 January 2016. <http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/365/1554/3065.short>.]].

The main issue of food waste is largely systemic. It is driven and exacerbated by the intricacies of climate, human geography, development, and consumer preference. As our population continues to grow, the issues of food insecurity will only intensify. Thus, in order to ensure livelihoods to future generations, it is imperative that we address the issue of food waste. It is through these efforts that we may finally avoid the world that Malthus feared two centuries ago.