In the late 1940s, French designer Jean Prouvé created a prototype for a steel and aluminum prefabricated house to be sent in pieces to the French colonies in what is now Niger and Congo. Prouvé’s architecture contemporaries lauded the houses as marvels of modern design. In 1951, the French military flew the houses to Africa, where they were assembled and housed colonial officials. Although the Maison Tropicale was meant to be a large-scale housing project, due to budgetary concerns the French government stalled construction after only three homes. When Niger and Congo gained independence in 1960, France fled the area, abandoning the prototypes. For nearly fifty years, local families lived in the houses and adapted them to an African existence. However, following a rise in interest in Prouvé’s designs in the 1990s, wealthy French art collector Eric Touchaleaume traveled to the sites of the houses. In 2000, he bought them from their current owners and took the three prototypes back to France, where they were restored, sold at auction for millions, and exhibited around the Western world.

Upon their return to France, architecture scholars and the media widely regarded the buildings as icons of modernist design, seen purely as industrial, modern objects. Journalists wrote of the buildings as being “saved” from complete disintegration or as being “rescued from squatters” who did not appreciate the architecture for the “design marvel” it was. This canonically-accepted Western narrative raises a series of questions about the complex web between architecture, colonialism, and the modernism movement in the twentieth century. Additionally, the history and movement of the Maison Tropicale prototypes have more recently sparked dialogue about the role of modern heritage in Africa, and of colonial Africa in the integration of modernist movements. The transition of Jean Prouvé’s Maison Tropicale prototype from colonial object to post-colonial object to “design icon” offers insight into historical connections between modern architecture and colonial power structures, as well as guidance for how to best proceed with post-colonial Western and African relationships today.

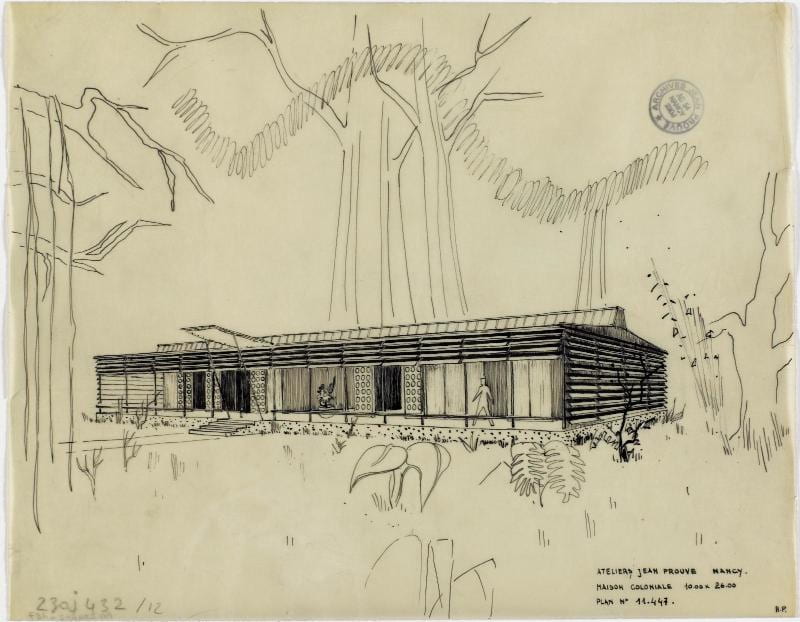

Jean Prouvé was born in Nancy, France, in 1901, and trained formally in the Art Nouveau movement as an ironworker who specialized in ornamental metalwork and furniture design. Although much of his focus was on industrial design, Prouvé’s appreciation for craftsmanship granted him a more creative side than a purely analytical approach as was used by many industrial designers at the time. Prouvé worked closely alongside other architects such as Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Robert Mallet Stevens, with all of whom he joined the Union des Artistes Moderne in 1930. Prouvé believed in constant improvement and the importance of developing and using new materials and production methods in the field of architecture. In 1947 he opened his own studio and factory, Ateliers Prouvé. Working both independently and in collaboration with colleagues, Prouvé invented a plethora of prefabricated components. His modular systems used aluminum, steel framing, and wooden paneling. As a strong believer in socialist principles, Prouvé centered his work around a dictum of “industrializing the habitat.” This industrialized habitat, he felt, could be achieved through the use of “standardized, factory-fabricated components that could be assembled in any geographical location.”

Modernism, standardization, and efficiency were guiding principles for wartime and post-war France, which saw the rise of a “technical elite” as it attempted to repair physical environments as well as the economy. Thus, the government commissioned much of Prouvé’s work in the 1930s and 1940s, including prefabricated emergency housing and barracks for the French military during the Second World War and a small social housing project called Meudon Houses for the Ministry of Reconstruction and Urban Planning.

At its apex, colonial France was one of the largest empires in the world. In Africa, French colonies include what is now Congo, Senegal, Mali, French Guinea, Burkina-Faso, Ivory Coast, Benin, Niger, Mauritania, Chad, Central African Republic, Gabon, Cameroon, and Togo. France’s relationship with these lands was one of extractive colonialism: the exploitation of natural resources, including agriculture, mining, and labor. The French administration created virtually no dialogue with locals, instead imposing taxation and slavery, which triggered unrest and violence throughout the region. France had strong imperialist ambitions, and one of its main goals was to bring “modernity” and “civility” to Africa, something which colonizers felt could be achieved with the use of European architectural styles.

For architects, designers, and engineers, the colonies were often seen as a laboratory or playground, a tabula rasa where they could try new designs in much wider spaces than urban France allowed. Different lands, materials, and climate constraints presented new design challenges, and over time a distinct French “regionalist architecture style” developed. This stance on colonial architecture completely disregarded the indigenous people and cultures of the area, and the buildings and cultural touchstones that were forced upon the native people melded with and changed their culture over time. This style of colonial architecture has not always existed – it had to be specifically created for an extractive, violent system, and without that system, the Maison Tropicale never would have existed.

In 1947, French authorities commissioned the Maison Tropicale as a colonial version of the prefabricated Meudon Houses Prouvé made for France, conceived out of a shortage of housing for colonists. The houses needed to be affordable and prefabricated so that parts could be stored in an airplane. They also had to survive the arid and tropical climates of the colonies, and be assembled quickly without expert construction skills. Once parts were on location, the houses took about two weeks to construct, compared to the months it took to build an expensive traditional European-style house.

To create space for the Maison Tropicale prototypes and other colonial settlements, the French military destroyed native homes and social centers. Forced, aggressive mass evictions occurred in both prototype locations of Niamey, Niger, and Brazzaville, Congo. The settlements became the “European part of town” where natives were not allowed to move freely, strictly limiting their interactions with the Maison Tropicale as a colonial object. The three prototypes served as a house and office for a junior high principal and a regional director for the Aluminium Français company, which was mining massive quantities of aluminum in Congo. There was an abundance of aluminum production in post-World War II France, and the Aluminium Français company in fact held a 17% share in Prouvé’s factory, forcing him to use as much aluminum as he could in his designs. The design of the Maison Tropicale prototypes is widely regarded as ingenious, as Prouvé pulled together many specific design requirements as part of the commission.

The Niamey house was the largest of the three prototypes, about 26x10m. The Brazzaville structures were smaller, about 10x18m and 10x14m and connected by a bridge. All three consist of a steel-frame interior cell with both fixed and sliding aluminum panel walls, surrounded by an aluminum-paneled balcony. The Niamey house, located in a more arid climate, rested on a concrete base covered in tiles to aid in cooling the structure, whereas the Brazzaville houses were elevated on steel columns in case of flooding, and to allow for the potential of a sloped site. Nearly every component of the building was designed to accommodate the hot weather. The walls were cut with numerous blue glass portholes and small open-air circles for ventilation, and wide eaves, complete with adjustable slats, for shade covered the balcony surrounding the central cell. The aluminum-paneled roof was itself a flue to pull hot air out of the space, with the ceiling constructed separately from the roof to add another insulating layer. Every aspect of the component parts was intricately designed. Prouvé used aluminum for its lightweight, and flat sheets to optimize air transit. The internal cell was pre-painted a neutral cream and green color and outfitted with thin steel columns to allow for adaptable subdivision of space.

The modernist design of the Maison Tropicale cannot be separated from its relationship with French colonialism and the view of the tropical environment as hostile, as something that needed to be controlled and regulated. France planned the structures as part of a “streamlined conquering” of Africa, with aluminum signifying technological control and the industrialized orderliness of the space relating to the French sense of calculated control over the colonies. Architectural and industrial design scholar at Swinburne University D.J. Huppatz wrote: “As both a modernist object and a colonial object, the Maison Tropicale stands at the logical endpoint of the Enlightenment narrative of progress, tangible evidence of reason’s triumph over the primitive.” That perspective was the dominant one in twentieth-century France and its notions continue to reverberate in academic thought today.

Prouvé himself never visited the colonies and his personal opinions toward colonialism are largely unknown. Still, he was proud that he was “industrializing the habitat” of the tropics through his detailed design work. The idea of “industrializing the habitat” without acknowledging the environment of colonialism and the tensions it created was a part of the Maison Tropicale’s failure as a housing project. Despite an aluminum surplus, it was expensive in comparison to local African materials, and the colonial officials living in Niamey and Brazzaville felt that the houses looked too out of place in the region. Prouvé continued to design other industrial components for the colonies, but only created three Maison Tropicale prototypes.

In 1960, after the French colonial regime withdrew from Africa, governmental instability sustained Western involvement, and massive debt continued to plague many formerly colonized countries as they struggled to develop after generations of trauma. Despite governmental involvement in other sectors, the French government essentially chose to forget about the infrastructure they left after withdrawing from the colonies, and for the most part, the rest of the Western world also forgot. However, beginning in the 1990s, a resurgence in Prouvé’s popularity struck art collectors and museums, and his designs began selling for increasingly high prices at auction. After hearing rumors of a wealth of Prouvé pieces in Niger and Congo, French antiques dealer Eric Touchaleaume traveled to the sites and bought all three prototypes, restoring them in France and selling them at auction for nearly $5 million.

The sale, transportation, and restoration of the Maisons Tropicales was logistically challenging and cost Touchaleaume over $1.5 million. The mogul later explained to the media that the high costs were worthwhile as he was “determined to salvage [the Maisons Tropicales] from ruin and bring them back to France.” The media clung to the triumphant narrative of the prototypes as “design icons” that needed to return to France to save them from “African destruction and squatters.” This narrative of repatriation is especially ironic given that an estimated 90% to 95% of sub-Saharan cultural artifacts are housed outside Africa, most of which were forcefully taken during the colonial period.

The restoration and current exhibitions of the Maisons Tropicales all repress the buildings’ African existence. Led by Touchaleaume, restoration teams refinished the houses in early 2000s France, but made a conscious choice to “keep a number of bullet holes in the sun shutters, to leave intact witness marks of the structure’s age that could be discerned through its apparent ‘newness’; and at the same time to be particularly provocative.” By keeping bullet holes, as opposed to natural aging as the only signs of the buildings’ African existence, curators fall into tropes of viewing “modern authentic” African items only as portraying a sense of violence and insecurity.

The Niamey house remains in Touchaleaume’s personal collection, but both Brazzaville structures have been displayed in France and around the United States, in exhibitions that portray the buildings as modern in a way that is “transcendent, neutral, and universal and thus beyond the specifics of culture, politics, or history.” This narrative silences a complex colonial history, corroborates European cultural superiority, and prevents further understanding of African history and social identities. Western art dealers and museums only lauded the houses as objects of value once they had assigned their own system of value to the structures, removing any African significance.

Although Western intellectuals have tried to erase the Maison Tropicale’s distinctly Nigerien and Congolese histories, those histories were very real. In the nearly fifty years the structures stood as post-colonial objects, African elites paid them little mind. Local families moved into and adapted the houses, which served various purposes throughout the late twentieth century.

In Brazzaville, several families moved in and out before ownership of the building settled with Mireille Ngatse after her father’s death. Alone and destitute following her father’s passing, Ngatse reminisced about finding comfort in the house in an interview: “That’s where I cried, where I talked to myself… it was very useful, this house helped me a lot.” Ngatse noted that despite not having electricity or running water, the house made her feel safe at night and cool in the heat, with her favorite part being the blue glass portholes because “it felt as if you were in the middle of the ocean.” When Touchaleaume came, Ngatse worked with a lawyer to settle the paperwork and was paid for the sale of the house, using the money to build new apartments on the property. Ângela Ferreira, an artist working on reconfiguring post-colonial narratives, said: “In Brazzaville, there’s an enormous amount of readaptation of the leftovers of the [Maison Tropicale] in order to create new architecture where people could inhabit.”

In Niamey, the Maison Tropicale stood uninhabited for the final 2-3 years of its post colonial existence – a tall concrete wall was at one point built around it, and the majority of neighborhood residents did not even know of its existence. However, to a few, it remained a vital structure. Amadou Ousmane, who grew up next door, remembered it as having good air circulation and at one point being used as a dance hall. Artonnor Ibriahine, a nomadic Tuareg woman and former resident of the house, told interviewers that she was unhappy that they took the house away. She felt that she had no rights in the situation as a poor person who only spoke indigenous languages. She said of its movement: “I feel sad and think of the house often. Especially when it rains. Now that it’s gone, I no longer have shelter from the rain.” The French collectors left behind only the concrete base of the house, which today is used only for prayer, surrounded by the tents of Tuareg people who have made it a part of their environment.

Western understandings of architecture view it as permanent, as woven into the history of a place. The removal of the Maison Tropicale leaves behind the African people who must still grapple with ideas of heritage in a post-colonial environment. A colonial historical memory means that Africans rarely have any choice in their heritage , and “in Africa, heritage is seen as a taboo topic,” explains Lydie Diakhaté, an independent film producer and art critic specializing in the arts and cultures of Africa and the African Diaspora. The Maison Tropicale prototypes were only a few of the many modern buildings the French constructed in the colonies, and for many Africans, those buildings do not have local value other than being odd-looking anomalies or painful mementos of a violent, traumatic past. The Western idea of conservation does not relate to post-colonial Africa, in part because of the influence of afro pessimism, a wide-reaching body of thought that holds that only Europeans have a true “heritage.” Many choose to believe that new constructions are the only architecture of value because they indicate a new, free Africa, or that colonial architecture like the Maison Tropicale does not “belong” to Africans.

However, despite the Western perspective that the Maisons Tropicales are not African objects, some scholars from both Africa and the West are working to develop an alternative narrative for the lasting legacy of the homes. One of the greatest questions opened in their bodies of work is: “Are these buildings African?” According to the patrimony definition outlined by the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, the Maisons Tropicale belong to Niger and Congo – however, strong lawyers and loophole-filled policies from the West make repatriation of African work in general immensely difficult.

Additionally, there is the question of when and how Africa adopts modern architecture – a distinctly European style – into their own vernacular, and how it influences African architecture today.

Portuguese artist Ângela Ferreira and Malian filmmaker Manthia Diawara have worked to question the dominant narrative of post-colonial relations between Africa and the West via a sculpture and photography exhibit for the 2007 Venice Biennale and accompanying documentary film, Maison Tropicale. Their work addresses notions “of shared cultural heritage – a notion which is controversial and does not often shape practice in Africa.” Ferreira believes that because the prototypes were built for Africa, (and would not exist without it) that they belong to Africa. Her exhibition included photographs of the spaces left behind from the removal of the houses, as well as life-size Prouvé components broken down into a prefabricated state. Diawara’s film adds a new, empathetic African context to the canon by interviewing former residents and locals surrounding the former sites of the houses. Their goal was to reconnect the separate African and Western viewerships and metaphorically give back the Maisons Tropicales to Africa

Over the course of its existence, the Maison Tropicale has transitioned from a colonial object, to a post-colonial object, to a “design icon.” This transition teaches us about the connections between stylistic and social impacts of architecture, and how vital it is to understand both when examining a structure. For example, the modernist stylistic elements of the Maison Tropicale are fundamentally intertwined with extractive colonialism at multiple levels. In Western culture, Africa is not associated with contemporaneity and thus is rarely viewed as a contributor to modernism. In the case of the Maisons Tropicales, both the decision to remove the houses and the aesthetic canonization that followed their return to France completely disregarded important African social contexts. The Western world currently sees the Maisons Tropicale only as modern architectural items and Prouvé only as a designer. The canonical postcolonial discourse tends to ignore the local African social history of modern colonial architecture. Through ignoring that history, countless important stories are lost.

The geographies of loss of the past and the silencing of African voices by Western involvement continues to shape contemporary African urbanisms. The refurbished Maison Tropicale prototypes could be returned to Niger and Congo. There, they could continue to be exhibited in a museum space or used as public spaces, aiding local people’s development of the complex post-colonial vernaculars that surround them today. Colonialism cannot be erased, but countries can work together to make reparations, and to support African perspectives, designs, and histories.

“Prouvé’s Moving Houses” is the winner of Expositions’s inaugural feature piece competition.

Zoe Pottinger

Contributor

France had strong imperialist ambitions, and one of its main goals was to bring “modernity” and “civility” to Africa, something which colonizers felt could be achieved with the use of European architectural styles.

The modernist design of the Maison Tropicale cannot be separated from its relationship with French colonialism and the view of the tropical environment as hostile, as something that needed to be controlled and regulated.

The removal of the Maison Tropicale leaves behind the African people who must still grapple with ideas of heritage in a post-colonial environment.

The Maison Tropicale has transitioned from a colonial object, to a post-colonial object, to a “design icon.”