As we enter a holiday season filled with feasts and festivities, Kristine A. Culp (University of Chicago), in conversation with John Calvin, invites us to consider the relationship between theology and the food we enjoy, the relationship between glory and gastronomy. In this essay, Culp considers how metaphors of taste found in Calvin’s writing on the Christian life offer one way of approaching experiences of glory and “aliveness.” It explores how experiencing the glory of living things involves sensory intensification and complexity, perceptual attunement, a felt experience of value, and the further intensification through recollection and recognition, thereby seeming, metaphorically speaking, to slow time and open worlds.

The November-December issue of the Forum features the Enhancing Life Project, which takes aim at addressing one of the most basic human questions—the desire to enhance life. This desire is seen in the arts, technology, religion, medicine, culture, and social forms. Throughout the ages, thinkers have wondered about the meaning of enhancing life, the ways to enhance life, and the judgments about whether life has been enhanced. In our global technological age, these issues have become more widespread and urgent. Over the last two years, 35 renowned scholars from around the world in the fields of law, social sciences, humanities, religion, communications, and others, have explored basic questions of human existence. These scholars have generated individual research projects and engaged in teaching in Enhancing Life Studies within their fields, as well as contributed to public engagement in various ways.

Over the next month and a half, Enhancing Life scholars associated with the Divinity School will share essays and reflections on the Enhancing Life Project that will explore its implications for their own scholarship and teaching. We invite you to join the conversation by submitting your comments and questions below.

Posted Essays:

- William Schweiker, Enhancing Life and the Forms of Freedom

- Anne Mocko, Attending to Insects

- Kristine A. Culp, “Aliveness” and a Taste of Glory

- Heike Springhart, Vitality in Vulnerability: Realistic Anthropology as Humanistic Anthropology

- Andrew Packman, Enhancing Racialized Social Life: The Implicit Spiritual Dimension of Critical Race Theory

- Michael S. Hogue, Resilient Democracy in the Anthropocene

- Darryl Dale-Ferguson, Envisioning a Fragile Justice

The Enhancing Life Project was made possible by a generous grant from the John Templeton Foundation, and the support of the University of Chicago and Bochum University, Germany.

by Kristine A. Culp

Those who, not content with daily bread but panting after countless things with unbridled desire, or sated with their abundance, or carefree in their piled-up riches, supplicate God with this prayer are but mocking him. For the first ones ask him what they do not wish to receive, indeed what they utterly abominate—namely, mere daily bread….

– John Calvin on the Lord’s Prayer (Institutes of the Christian Religion, 3.20.44)

Things that claim to be glorious—battles, leaders, buildings, nations, for example—can in fact be profoundly ambiguous. Glory by whose perception? By what measure? We know too well of persons and entities that boast of glory when they are merely oversized. One Yale University study found that the visibility of financial wealth—ostensibly one form of glory—makes the rich more aggressive and exacerbates inequality. Another study found that those who were driving fancy cars were more likely to run through crosswalks where pedestrians were waiting. In the sixteenth century, Martin Luther was so alarmed about the religious ostentation and presumption in his day that he condemned the very idea of a theology of glory, rejecting it for a theology of the cross that “calls the thing what it actually is.”

Against the good doctor Luther’s advice, I’m going to delve a little deeper into the glory of living and made things. I follow Irenaeus, the second-century theologian and bishop of Lyon, who said that the glory of God is the human fully alive. Aliveness, not supersizing or aggrandizement, is what Jesus called attention to when he taught about the splendor of wild lilies. When African American sanitation workers marched in Memphis in 1968 bearing signs saying “I am a Man,” their appearance in the public square illuminated inhumane, unjust social and economic conditions, while their signs announced the dignity that was already manifest in their persons—the glory of the human fully alive.

I. “Aliveness”

How does glory relate to enhancing life? To consider what might enhance—or, conversely, endanger—life, one must be able to picture “life” capaciously and critically. As Czech philosopher Erazim Kohák has observed, “It is much easier to decry our dehumanization than to reclaim our humanity.”1 Living creatures and life systems must not only be able to resist dangerously subtle, coopting, and sometimes vicious threats, but also to “reclaim” their full glory. The notions of “resilience” and “grit,” developed in risk management literature, psychology, and now by theologians and other scholars, make important, necessary contributions to this task. But we as scholars and as persons also have to consider what it means for human and other vulnerable creatures and life systems to be fully alive—to be transformed toward aliveness, not only to resist and be resilient to damage and threats of endangerment, very real as they are.

What do I mean by aliveness? How does it appear? Precisely where life is most vulnerable to being changed. For example, in her poem, “Autumn Passage,” the American poet Elizabeth Alexander considers her mother-in-law’s dying and how it is accompanied by others. She writes, “On suffering, which is real…”

For her glory

that goes along with it,

glory of grown children’s vigil,

communal fealty, glory

of the body that operates

even as it falls apart, …

as it dims, as it shrinks,

as it turns to something else.2

Here, “glory” is not separated from living. Alexander’s poem offers analogies between a singular threshold at the end of life and decisive crossing points in other lives and forms of life. Her mother-in-law’s dying body manifests both suffering and glory in its last living.

The poem also attests to the “glory” of grown children who keep watchful vigil and, in lines I didn’t cite, to a “dazzling toddler.” When asked about “vegetables,” he says “eggplant,” and “chrysanthemum” for “flower,” displaying the full reach of his young linguistic powers. Go any farther, though, and he would surely tumble over his large words into incoherence. Incoherence haunts other realities in this “autumn passage,” including giant “September zucchini” and “other things too big”—such as a nation struggling with the immensity of “vanished skyscrapers.” Likewise, the toddler’s dying grandmother is at full capacity. Her body, her life, her person, cannot undergo more without turning into something else.

The poem attends to a quality of aliveness that is interconnected with intellection, affection, sensation, loyalty, bodily processes, relationships and social life (possibly also with vegetable life and the life of nations). What appears glorious? Not some sort of embellishment or something superadded to life. Not an invulnerable state beyond suffering and living. Rather, glory is intertwined with the vulnerability of all living things to being changed.

In this poem and in general, glory signals a threshold where life seems to take on a magnificence that is not self-generated/generating. Correlatively, glory signals a threshold beyond which life may become diminished, begin to unravel, or become endangered. A ripe pear, fragrant with delicate sweetness, is also on the cusp of decay. Its glorious taste depends on that threshold, not on the defeat of the life cycle. The poem’s “dazzling toddler” won’t become more glorious when he masters the use of “eggplant” and “chrysanthemum”—but the full aliveness of his post-toddler self may become manifest in different ways.

Long ago, Jesus invited his listeners to consider the unadorned splendor of lilies in relation to the lesser glories of King Solomon and their own anxious pursuits. My research considers the aliveness of living things as a quality or capacity, and it asks how such aliveness can be recognized, respected, and undergirded. What does it mean to “reclaim our humanity”—or more broadly, to reclaim the aliveness of living things—in this global and historical context of profound endangerment and of unprecedented powers for “enhancement”? I’m not arguing for, say, a christological interpretation of lilies or offering a theology of beauty. Rather, I’m exploring the experience of aliveness as a sensory, affective, temporal, always interpreted, value-laden phenomenon that can bear creaturely, moral, and religious significance. I have been considering the glory of living and made things such as wild lilies, cultivated gardens, the push and pull of Mark Rothko’s paintings, as well as in shared spaces of public life and in individual lives. I interpret these experiences and examples with the help of practical theological wisdom that has been articulated over the ages in relation to sensory perception, affections, and the use of visual art and architecture, music, food.

II. A Taste of Glory

Among potential resources for this project, John Calvin’s theology may seem an unlikely prospect given his bracing critique of idolatry and his dour reputation. The sixteenth-century theologian was particularly suspicious of the deceptions of visual culture and of precepts about higher religious life. Yet, he was also a humanist and reformer dedicated to teaching theology as an art of living and to reconstructing ecclesial and civil life alongside a thorough-going critique of idolatry. In this section, I trace what may be an unexpected theme in Calvin, — particularly of “sweet taste”—and how it relates to the satisfaction of need (hunger), the sensory perception of glory, the capacity of things to bear aliveness, and to sanctification as vivification.3

Calvin as gastronome?

John Calvin’s discussion of the Lord’s Supper in his 1559 Institutes of the Christian Religion evokes experiences of the nourishment and savor of food:

We see that this sacred bread is spiritual food, as sweet and delicate (suave et delicatum) as it is healthful for pious worshipers of God, who in tasting it, feel that Christ is their life, whom it moves to thanksgiving, for whom it is an exhortation to mutual love among themselves.4

He assumes that his readers have had analogous experiences of their own hunger being met, and that they can draw on those sensations of repair, satisfaction, and vivification to experience the restoring grace of God.

There are many notable things in this passage. What catches my attention now is that the man who wrote it must have known the pleasures of the taste of good bread. Sweet and delicate, satisfying, restorative—my mind reconstructs the sensory delights of a baguette fresh from a local boulangerie in France. Doubtless that is a fine bit of anachronistic imagining, as may be picturing Calvin as a possible gastronome. But perhaps this whimsy conveys an insight that is not always fostered in eucharistic rites or in readings of Calvin: namely, that enjoyment can tell us about the goodness and power of life, especially when cultivated through interpretation, communal remembrance, conscience, and attention to the needs and well-being of others.5

The passage is located deep in one of the Institute’s longest chapters, a chapter that was lengthened by three decades of swirling controversies about the meaning of the sacrament. The specific context is a discussion of “unworthy partaking,” but implicit here is the question of whether the finite is capable of bearing the infinite, finitum capax infiniti? Calvin answers yes and no. The bread retains its integrity and its spiritual power remains integral no matter the reception, but the bread cannot work magic. Its savor and nourishment have to be received reverently in faith (as a good gift of God that bears the life-giving power of Christ) and in a way that fosters the well-being of others.

Whether Calvin is writing about controversies or worthy and unworthy participation, he never loses track of the fact that he is writing about a supper. Bread and wine, particularly the experience of being nourished and refreshed by them, offer a central analogy for his interpretation of the Lord’s Supper and the work of Christ. “[A]s bread nourishes, sustains, and keeps the life of our body, so Christ’s body is the only food to invigorate and enliven our soul. When we see wine set forth as a symbol of the blood, we must reflect on the benefits which wine imparts to the body.… These benefits are to nourish, refresh, strengthen, and gladden.”6

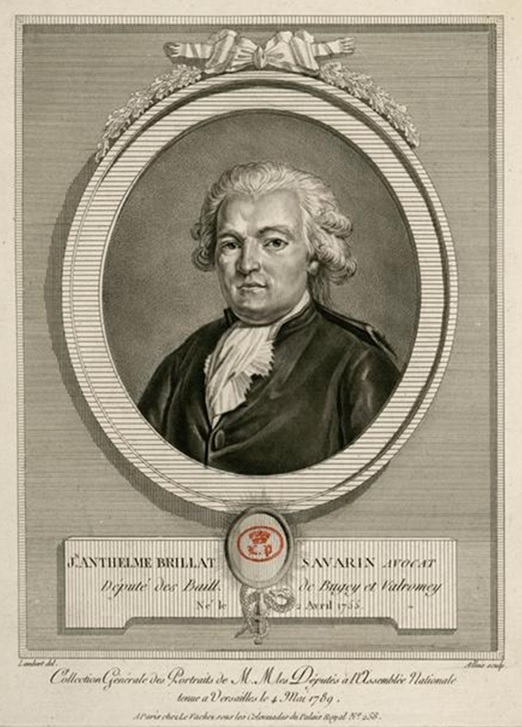

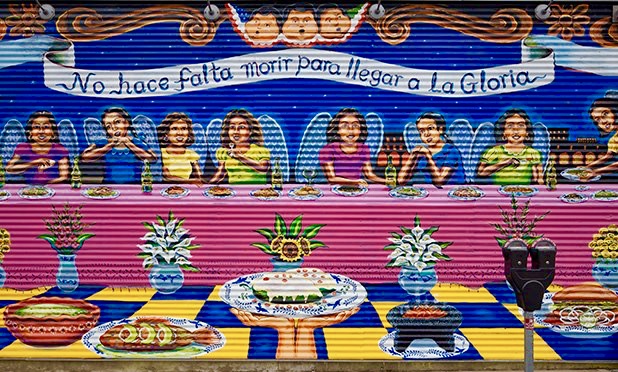

The conjunction of need and pleasure in these passages brings Calvin closer to gastronomy than one might expect. Three centuries later, fellow Français Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who became known as the father of modern gastronomy, described the pleasure of eating as “a certain special and definable well-being which arises from our instinctive realization that by the very act we perform we are repairing our bodily losses and prolonging our lives.”7 He argued that, among all sensory pleasures, the pleasure of taste is greatest because it can be shared with all persons and nations and experienced throughout life, and not ultimately because of the rarified heights it may reach. According to Brillat-Savarin, the pleasures of eating, “the actual and direct sensation of satisfying a need,” can be modified, intensified, and extended by the pleasures of the table.8 Understood this way, the art of satisfying hunger (when practiced well) is crucial for all people and times, especially for times of scarcity and strife. M.F.K. Fisher, the American writer and Brillat-Savarin’s translator, observes: “[O]ne of the most dignified ways we are capable of, to assert and then reassert our dignity in the face of poverty and war’s fears and pains, is to nourish ourselves with all possible skill, delicacy, and ever-increasing enjoyment…. And with our gastronomical growth will come, inevitably, knowledge and perception of a hundred other things, but mainly of ourselves.”9

Calvin’s approach to gastronomy, if we can call it that, is perceptual, sociocultural, moral, and theological. He doesn’t write about daily meals or fancy dining, of course, but about sacramental signs. Yet he too assumes that the delight of taste is something that everyone shares and, therefore, that the modest but life-renewing pleasures of taste are especially suited for expressing the deepest mysteries of Christ’s benefits. Calvin is interested not only in human experiences of need and pleasure, but also what God purposes through these pleasures, and especially how human life might be attuned and reoriented in relation to an awareness of God’s goodness and good gifts.10

Whereas Brillat-Savarin and M.F.K. Fisher write about cultivating enjoyment to vivify life and contribute to human well-being, Calvin writes about cultivating the conscience and using freedom in order “to live, not luxuriate,” to aid the neighbor, and to glorify God. Brillat-Savarin, distinguishing gastronomes from gluttons, seeks to temper excessive consumption so that pleasure can be extended. His accent is humanist as well as hedonist: gastronomic pleasure is dependent on and conjoined with an awareness of creaturely vulnerability to perishing and emerges first from the satisfaction of hunger (a universal human need). Calvin also rejects gluttony, but as a form of ingratitude and obliviousness. Calvin seeks a kind of pragmatic moderation—a heart “tempered to soberness” or a “clean conscience” (3.19.9)—that will guide the use of freedom and of enjoyment.11

Both approaches contrast with the thrum of unrelenting consumption that permeates modern Western cultures and threatens life on the planet. Cultural critic Robert Pogue Harrison says modernity’s anxious craving for “more life” is, at best, “a paltry and degenerate hedonism.” It is a frenzied, aimless, and destructive condition in which “[w]e relate to the present in the mode of impatience, to the future in the mode of despair, and to the past with a fool’s ingratitude. Where gratification takes the place of gratitude, as it does in our senile new world, gluttony becomes a destiny.”12 According to Harrison, the aim of “genuine hedonism” as taught in the ancient school of Epicurus, is the cultivation of happiness through the transformation of mortal life, and by fostering patience, hope, and gratitude. “It is the ungratefulness in the soul that renders the creature endlessly lickerish of embellishments in the diet,” Epicurus said.13

Use and enjoyment

Despite what seems to be a shared concern for cultivating gratitude, as far as I can tell, Calvin had nothing good to say about Epicurus or Epicureans. On any matter. Beginning with his first book, a commentary on Seneca’s De Clementia (1532), Calvin echoed Stoic scorn for the Epicureans as deriding providence and leaving everything to chance. Yet he didn’t simply side with the Stoics; as commentators have noted, Calvin’s theology of providence mediates between Epicurean chance and Stoic fate.14 Similarly, although Calvin is no hedonist when he writes about the pleasure of taste, he also rejects Stoic cultivation of apathy. To recast his own phrasing, for Calvin luxuriating is the problem, enjoying the food we eat to live is not.

By contrast, Augustine, writing at the turn of the fourth century, stayed close to his Stoic teachers on this matter. He sought to use the goods of this life but not enjoy them (utor non frui). “When I’m going to take alimentation, I should resort to it the way I resort to medication,” he resolves. He grants that “we restore the everyday damage to the body by eating and drinking,” which is “much of the time an agreeable experience”—an experience that Brillat-Savarin later points to as a baseline of shared humanity. But Augustine’s baseline is set beyond mortal life, “when this perishable body will clothe itself in everlasting imperishability,” a time when, he envisions, God will “destroy food and the stomach, killing our need with miraculous fullness.” That vision of imperishability and the cessation of desire affects Augustine’s evaluation of hunger and thirst. “As things are now, the necessity of eating is sweet, and I fight daily against that sweetness so that I’m not taken prisoner by it. I fight a daily battle through fasts….” Augustine pinpoints the crossover from “the irritation of needfulness” (hunger and thirst!) to satisfaction as the place where “the snare of sensual desire is waiting for me.” What makes the crossover seem so dangerous to Augustine is the ambiguity of when that line is crossed: “often it’s unclear whether the essential care of the body is asking for help, or hedonistic self-deceit is slyly demanding that I cater to her.”15

Few thinkers are more wary of self-deception than is Calvin, and he esteems no theologian more than Augustine, but even Calvin thinks Augustine drew the line at the wrong place. Calvin rejects the distinction between use and enjoyment made by Augustine and the Stoics because he finds the goodness of God evident in creation and he interprets piety as a response to God’s goodness.16 “Did he [‘the Author of creation’] not, in short, render many things attractive to us, apart from their necessary use?” (3.10.2), he asks. I imagine his voice rising in consternation: “Away, then with that inhuman philosophy [Stoicism], which, while conceding only a necessary use of creatures, not only malignantly deprives us of that lawful fruit of God’s beneficence but cannot be practiced unless it robs man of all his senses and degrades him into a block” (3.10.3).17

The central question that Calvin frames about enjoyment is whether it detracts from a godly or moral life, that is, from a piety rightly ordered to God and to neighbor. He answers no, not when enjoyment participates in the reality of a good creation and the purposes of a gracious God. His treatment is closely related to his discussion of love of neighbor and self-renunciation in 3.7.5-6 (which features endurance and patience, not apathy) and of Christian freedom in 3.19. Calvin’s confidence in the goodness of God and in God’s well-ordered providence allows for a surprising amount of freedom in the Christian life and also charters freedom for ensuring the well-being of others through law, the church, and civic institutions.

Calvin rejects the bifurcation of the Christian life into a two-tiered ethics in which some are vowed to ascetic counsels of perfection and thus deemed more righteous. With it, he also rejects affective and emotional disconnection from the world as a higher ethical standard (which is not to say that he rejects constraint). Calvin instead offers a multi-dimensional picture of the Christian life as fully engaged in a created world with others, undergoing suffering and joy, fearful of divine judgment and grateful for the gifts bestowed by God, and existing in anticipation of fuller life in God. For him, conscience guides an ongoing struggle to find the proportionate mean, an integrity (3.6.5), by fostering self-renunciation or humility that cultivates devotion to God and a sense of self proportionate to God and that attunes Christians to the neighbor through the cultivation of sincere love (vs. a legalistic duty to love) and to the created goods of life through gratitude and enjoyment (vs. use without enjoyment).18

In Calvin’s reframing of the relation of use and enjoyment, it matters more not less that Christian life is directed toward others and benefits (utilis) the neighbor. “All the gifts we possess have been bestowed on us by God and entrusted to us on the condition that they be distributed for the neighbor’s benefit” (3.7.5). Calvin also reframes the discussion insofar as his ultimate emphasis falls on what is beneficial rather than what is needful. Rightly receiving Christ’s benefits already assumes that the benefits are good both in the sense of being suited to creaturely need and in the sense of conveying value or enjoyable goodness. Yet Calvin is also intensely aware of the inevitable disruption and loss of capacity to enjoy God. There is accordingly, an ambivalence in this mixed approach—e.g., freedom and/or “rules,” enjoyment and/or moderation—that is magnified in an ambiguous history of effects.19 Suffice it to say that Calvin affirms the inherent value of creaturely life and interprets creaturely enjoyment as part of divine providence, but his rejection of utor non frui may not markedly heighten enjoyment of the goods of life. What results instead is a more complex, and perhaps more complexly ambiguous, relation between what is needful and what is pleasing.20

Tasting life and God

The broader discussion in which Calvin takes up “use and enjoy” is the repentance or regeneration of the Christian life. “Repentance is the true turning of our life to God, a turning that arises from a pure and earnest fear of him.” It is ongoing, not once and for all, and consists of two parts, mortification and vivification (3.3.5-9). Mortification, self-denial and bearing the cross, is “the sum of the Christian life,” he emphasizes in 3.7-8. His prose crackles like lightning in a storm, “We are not our own”; the repeated reply thunders, “We are God’s.” In 3.9, when he turns from mortification to mortality, Calvin’s dour reputation seems rightly earned. Calvin creates the strongest possible contrast between “this life” and “the future life.” Those who are dazzled by wealth and happiness in this life, he remarks, would do well to heed what the philosophers (Plato) teach, namely that the body is a prison and this life is a sepulcher. Yet, he adds, “this life, however crammed with infinite miseries it may be, is still rightly to be counted among those blessings of God which are not to be spurned” (3.9.3). This sounds unconvincing and not much less despairing to many contemporary ears—or perhaps to all but those who are suffering overwhelming disruption, pain, loss, or persecution. Glimmers of vivification emerge in this bleak chapter, but mostly to backlight the limits of mortal life: “We begin in the present life, through various benefits, to taste the sweetness of the divine generosity in order to whet our hope and desire to seek after the full revelation of this [in the life to come]” (3.9.3). Vivification seems to get short shrift both in Calvin’s text and in this life.

Is vivification relevant to mortal, creaturely life? Or, is the taste of the sweetness of God a threshold beyond mortality, a taste of immortality? Even if human creatures can cross this threshold in contemplation of God, should they expect any enjoyment in their daily living? As if to anticipate such questions, Calvin turned next to affirm both use and enjoyment of the goods of this life. For him, there is more to the Christian life than mortification, bearing the cross, being patient in suffering, and focusing on hope to come—as primary and irreplaceable as those are. It might be more than enough to be resilient and resistant in the face of the world’s immense suffering and injustice—not to mention mundane distractions and corrupted capacities. But Calvin thought that neither the Epicureans nor the Stoics got it quite right. As we have seen, he insists that both suffering and enjoyment are part of creaturely life that is responsive to God, neighbors, and the world.

For Calvin, the bread’s sweet and delicate (suave et delicatum) taste is not due to the local boulangerie, of course, but to its association with the goodness of God. “Delicate,” in English and in its Latin root, suggests something is finely wrought and, often, pleasurable or delightful. Suavitas and dulcedo, closely related terms that are translated by Ford Lewis Battles as “sweetness,” are found throughout Calvin’s work. Calvin filled the Institutes and his commentaries with numerous references to the sweetness of God and to God’s benefits.21 The metaphor of tasting God’s sweetness can be traced back at least to the Psalms, texts which deeply inform Calvin’s thought and, through newly commissioned hymn settings, inflect Reformed worship. He follows Augustine, Bernard of Clairvaux, and others in discussing the sweet taste of God. According to historian Mary Carruthers, in the Middle Ages, “Dulcedo Dei is a profound theological and mystical experience. . . . ‘Sweet’ are also the pleasures of sensory appetites, social games and gatherings, and holy contemplation.” She continues, “But what unites all these disparate experiences, from appetite to contemplation, is a fundamental observation that what is ‘sweet’ is both pleasing and beneficial.”22 Use and enjoyment. According to Carruthers, for many late medieval spiritual writers, “to ‘taste’ God is a more completely knowing experience than even to ‘see’ God.”23

Augustine’s meditations on the relation of bodily sensation, including the pleasure of taste, to the knowledge of God are some of the most lyrically, even luxuriously, styled passages of the Confessions.24 “But what do I love, in loving you?” he asks. Not sensory experiences or remembered sensations of agreeable light, melodies, aromas, “honey on the tongue,” and welcome physical embrace. Rather, “a certain light, and a certain voice, and a certain fragrance, and a certain food, and a certain embrace” are recognized as the “you” to whom and about whom Augustine confesses. Within God, “something has flavor that gluttony doesn’t diminish, and something clings that the full indulgence of desire doesn’t sunder” (10,8). Augustine recognizes analogues and then further negates the similarities and amplifies the differences. His rhetorical negation and amplification parallel ascetic practices, especially of fasting and celibacy, and ascent to God in prayer and contemplation. As hunger and sexual desire are transmuted to longing for God, they are first increased and not satiated. “I tasted you, and now I’m starving and parched; you touched me, and I burst into flame with desire for your peace” (10,38). The soul is stretched away from the earthly food chain and beyond anything that could be measured by gluttony; it blazes (self-immolates?) out of nature and history into God.25 “Once I cling to you with all I am, I’ll no longer have pain or hardship. My life will be alive when the whole of it is full of you” (10,39). This is the “miraculous fullness” to which Augustine refers in the passage about the divine destruction of food, the stomach, and “the irritation of necessity” (10,8).

Augustine’s “miraculous fullness” imagines being so sated with divine abundance that even what might have counted as gluttony is surpassed. God annihilates all pain, including hunger, and all capacity for hunger (the stomach), enjoyment (food), and thus desire itself. By contrast, Calvin pictures the eternal enjoyment of God.26 “God contains the fullness of all good things in himself like an inexhaustible fountain” (3.25.10). The ever-moderate Calvin warns, “just as too much honey is not good, so for the curious the investigation of glory is not turned into glory…” (3.21.2).27 He counsels his readers to “keep sobriety” so that they are not “overcome by the brightness of heavenly glory” (3.25.10). He dismisses as “superfluous” certain speculations about how abstinence from food as a symbol of eternal blessedness is related to the final restoration. Calvin rejects speculative knowledge in favor of knowledge of God conveyed in the experience of creaturely enjoyment of God: “[T]here will be such pleasantness, such sweetness in the knowledge of it [heavenly glory] alone, without the use of it, that this happiness will far surpass all the amenities that we now enjoy. . . . [A]n enjoyment, clear and pure from every vice, even though it makes no use of corruptible life, is the acme of happiness” (3.25.11).

Calvin concludes Book 3 with his excursus on the final resurrection and his picture of eternal enjoyment, but that is not the final word of the Institutes. The full communal, social, and political outworking of God’s interrelation with the world and of Christians’ relation and responsibility with others follows. Calvin places his account of partaking in the Lord’s Supper at the center of Book 4, and renders it in a powerful style that also makes it the rhetorical highpoint of the book. That importance mirrors the centrality of shared worship and of vivification, not only mortification, in his account of individual, ecclesial, communal, and political life. At the table of the Lord’s Supper, human creatures lift up their hearts to God, and they taste, are restored and enlivened by, and share together the sweetness of God. This is vivification. The taste of good bread shows humans to be vulnerable creatures who are susceptible to transformation, for good and for ill, who suffer hunger and sometimes unspeakable devastation, and who also taste—and enjoy—glory.

III. Conclusion

The whimsy about Calvin and a good French baguette points to the role of taste and to the enjoyment that comes from extending the pleasure of eating through the pleasures of the table, in his case, the Lord’s Supper. Calvin all but says that experiences of nourishment and pleasure that come with the satisfaction of hunger can instruct the right observance of the sacrament, not vice versa. Attending to the taste of good bread—sweet, delicate, restorative, satisfying, gratefully received and shared—allows a consideration of “aliveness” in relation to Calvin’s discussion of the mortification and vivification of life in God. We, too, can consider the satisfaction of hunger—the repair of bodily losses and the restoration of a sense of well-being—to be a baseline experience of the enhancement of life.

Calvin’s attention to need, benefits, enjoyment, and sweet taste is one entry point for expanding, relocating, and even redefining visual aesthetic valuation within a more capacious field of sensory and affective knowledge, which itself requires reference to memory, recognition, and interpretation. This is some of what I am exploring in considering the aliveness of life with the help also of the splendor of wild lilies, the push and pull of Rothko’s paintings, and in human living and dying. In such experiences, the aliveness of life is deeply recognizable but cannot be possessed; it utterly depends upon but goes beyond perception and memory. To characterize it in a quasi-phenomenological manner, experiencing the glory of living things may involve sensory intensification and complexity, perceptual attunement, a felt experience of value, and the further intensification through recollection and recognition, thereby seeming, metaphorically speaking, to slow time and open worlds.

We, as individuals and as fellow creatures with shared projects in a vast cosmos, are vulnerable to enhancement and to endangerment. So much seems possible, knowledge of the infinitesimal cellular exchanges of the brain and of the dark matter of the universe, and so much seems threatened or unsustainable. We will not fathom these vast enigmas, but stopping to savor and give thanks for the taste of good bread, with its reminder of shared human need and the joy of receiving and sharing food, may allow us to slow the anxious frenzied consumption of modern existence, to ponder the power and limits of our lives, and to take up the responsibilities to which we are summoned—responsibilities to and with neighbors, strangers, and all living things. ♦

Kristine A. Culp is Associate Professor of Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School and Dean of the Disciples Divinity House at the University of Chicago. Kris Culp works in constructive theology. She is the author of Vulnerability and Glory: A Theological Account (Westminster John Knox, 2010), one of the first theological works to connect multidisciplinary conversations about environmental and economic vulnerability with theological anthropology and sociality. She is the editor of The Responsibility of the Church for Society and Other Essays by H. Richard Niebuhr (2008), which collected Niebuhr’s various writings on ecclesiology and Christian community for the first time. Her essays have addressed protest and resistance as theological themes, feminist and womanist theologies, and “experience” in contemporary theology. She is currently working on a monograph entitled, “Glorious Life?,” which is supported by the Enhancing Life Project. It engages historical-theological debates about the glory of given things and of made things, and fosters critical sensibilities about the aliveness of life amidst the challenges and complexities of contemporary life. She also serves as a member of the Commission of Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches.

Kristine A. Culp is Associate Professor of Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School and Dean of the Disciples Divinity House at the University of Chicago. Kris Culp works in constructive theology. She is the author of Vulnerability and Glory: A Theological Account (Westminster John Knox, 2010), one of the first theological works to connect multidisciplinary conversations about environmental and economic vulnerability with theological anthropology and sociality. She is the editor of The Responsibility of the Church for Society and Other Essays by H. Richard Niebuhr (2008), which collected Niebuhr’s various writings on ecclesiology and Christian community for the first time. Her essays have addressed protest and resistance as theological themes, feminist and womanist theologies, and “experience” in contemporary theology. She is currently working on a monograph entitled, “Glorious Life?,” which is supported by the Enhancing Life Project. It engages historical-theological debates about the glory of given things and of made things, and fosters critical sensibilities about the aliveness of life amidst the challenges and complexities of contemporary life. She also serves as a member of the Commission of Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches.

- Erazim Kohák, The Embers and the Stars: A Philosophical Inquiry into the Moral Sense of Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 110. ↩

- Elizabeth Alexander, “Autumn Passage,” in Crave Radiance: New and Selected Poems 1999-2010 (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2010), 174. ↩

- The following sections modify and expand work originally published as “A Taste of Life: or, Notes on Joy,” in Günter Thomas and Heike Springhart, eds., Responsibility and the Enhancement of Life: Essays in Honor of William Schweiker (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlangsanhalt, 2017), 191-203. ↩

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill and trans. Ford Lewis Battles, Library of Christian Classics, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960), 4.17.40; see also 4.17.43. ↩

- Several dimensions of goods are implied in this passage: the basic good of the satisfaction of hunger; the social good of shared life and care for others; the religious good of power united with value (worth). Memory, interpretation, and participation further saturate the experience. These already saturated goods are reinterpreted by and serve to interpret the power of “Christ” in their lives. “To feel that Christ is their life” suggests the satisfaction and enjoyment of multiple goods at once. ↩

- Calvin, Institutes, 4.17.3. Calvin characterizes it as an “analogy” and “a sort of analogy.” ↩

- Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste; or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, trans. and ed. M.F.K. Fisher (1949; New York: Everyman’s Library, Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 52-53. ↩

- See Brillat-Savarin’s closing vision of “the temple of gastronomy” which rises “on the two unshifting cornerstones of pleasure and of need,” 444. ↩

- M.F.K. Fisher, “How to Cook a Wolf,” collected in The Art of Eating (New York: Macmillan, 1990), 320-22. ↩

- See, e.g., Calvin’s commentary on Gen. 43:34 in Joseph Haroutunian, ed. and trans., with Louise Pettibone Smith, Calvin: Commentaries (1958; Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 349. See also Bruce Gordon, Calvin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 147. ↩

- Calvin counsels moderation against the dangers of “unbridled excess” and overfastidiousness (3.10.1, 4). Christians have freedom to use “things indifferent,” adiaphora, “provided they are used indifferently” (3.19.9). ↩

- Robert Pogue Harrison, Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 82. “More life,” Lionel Trilling’s phrase, is taken up by Harrison in chapters 14 and 15 passim. ↩

- Quoted in N.W. De Witt, Epicurus and His Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1954), 327, and as cited in Harrison, 79. ↩

- See Charles Partee, Calvin and Classical Philosophy (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1977; repr. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2005), 121-23, and chs 7 & 8 passim. ↩

- All quotes are from Sarah Ruden’s new translation of Augustine, Confessions (New York: The Modern Library, 2017) 10,43-44. In Augustine’s narrative, there is no intermediate zone or no innocuous pleasures that might be the equivalent of Calvin’s adiaphora, so even the “sweet” necessity of eating borders perilously on the edge of illicit pleasure. He sexualizes and eroticizes this peril as the threat of seduction by a demanding “her.” See the translator’s note on 10,52. ↩

- “Calvin thought refusal to enjoy God’s gifts was tantamount to rejecting (God’s) goodness,” William J. Bouwsma explains in his influential portrait of the historical Calvin. John Calvin: A Sixteenth-Century Portrait (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 135 and 135-39 passim. Calvin defines piety as “that reverence joined with love of God which the knowledge of his benefits induces” (1.2.1). ↩

- Calvin judges Stoicism to both hinder enjoyment of God’s benefits and suppress the reality of suffering, pain, and condemnation. Arguably Augustine, perhaps also the Stoics, had a more variegated account of pleasures than the utor non frui formulation suggests. For example, Mary Carruthers discusses Augustine’s sermon on Romans 8:30-1 (Sermones, 159.2 PL 38.868) in which he draws the line not between use and enjoy, but between justified and unjustified pleasures. “Certain things naturally please our human fragility, as food and drink please those eating and drinking…. Food that is not prohibited by religious law pleases our taste; also pleasing are the banquets of sacrilegious sacrifices. The one justified, the other not.” Taste (like the other senses) registers pleasurable sensations, but is unable to make moral judgments about the sensations. It is rather justice that weighs pleasure, and its equilibrium may also bring delight. Carruthers notes the similar idea of ‘grades’ of pleasures in Cicero, De finibus, 2. The Experience of Beauty in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 58. ↩

- C.f. H. Richard Niebuhr on the “fitting” in The Responsible Self: An Essay in Christian Moral Philosophy (New York: Harper & Row, 1963; Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999). See also Mary Carruthers’s discussion of the “honest finial” and of a style that suits the dignity of a place or thing in Beauty, 112-25. ↩

- I’m thinking, for example, of John Corrigan’s Emptiness: Feeling Christian in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). What Corrigan calls the “feeling of emptiness” can be found in Calvin’s call to “mortify” and “depart from ourselves,” e.g., Institutes, 3.3.5, 3.7; see also 3.8.3: “to feel your own incapacity.” I understand Bouwsma to be addressing this sort of ambivalence in his “sixteenth-century portrait” of “two Calvins, coexisting uncomfortably within the same historical personage” (230). An adequately robust approach to enhancing life will involve more than adjudicating the right mixture of use and enjoyment. ↩

- For example, to answer “how far the enjoyment of food and wine is allowable,” Calvin introduces new “rules” of moderation and stewardship (tested by the rule of self-emptying love for neighbor) and for the use of freedom. See also Carruthers on dulcis (pleasure) and utilitas (benefit) in Augustine, Bonaventure, and Aquinas (Beauty, 78-9). ↩

- See John Hesselink, “Calvin, Theologian of Sweetness,” Calvin Theological Journal 37 (2002): 318-32. ↩

- Carruthers, Beauty, 89. ↩

- Carruthers, Beauty, 128. ↩

- “Luxurious” is Carruthers’s characterization in Beauty, 15. ↩

- See Andrea Nightingale, Once Out of Nature: Augustine on Time and the Body (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), esp. 10-22, 111-15, 188-96; also see Margaret R. Miles, Desire and Delight: A New Reading of Augustine’s Confessions (New York: Crossroad, 1992). ↩

- He also pictures the eternal suffering of God’s wrath by those who are not chosen. I should note that I do not assume that Calvin’s theology is fully adequate even when interpreted capaciously, and that I am also reading Augustine’s and Calvin’s depictions of a multi-leveled reality metaphorically and analogically not literally. ↩

- He says this just before embarking on pages about election and double predestination. He goes down this road citing scripture and Augustine copiously, rather than keeping his own counsel. ↩