In “On Political Theology and Religious Nationalism,” Benjamin Lynerd (Christopher Newport University) responds to David Barr’s (University of Chicago) essay featured in this month’s issue of the Forum, “Evangelical Support for Trump as a Moral Project: Description and Critique.” The rise of Donald J. Trump to the presidency has caused a crisis of misunderstanding in American politics. From the perspective of his critics, his ethos, rhetoric, and politics are so self-evidently evil, they cannot imagine how anyone could support him from anything other than depravity or ignorance. Barr’s essay makes the case that there is a deeper meaning beyond this apparently obvious one, and realistic political analysis requires that we recognize it. Barr argues that many American evangelical Christians support President Trump as an expression of a positive moral vision for American government and society.

Lynerd’s response identifies an important question underlying Barr’s piece: Does evangelical support for Donald Trump stem from political theology or from what others have identified as “Christian nationalism”? In response to this question, Lynerd argues, “The reality is that religious nationalism and political theology, though distinct lines of thought, overlap in significant ways among rightwing evangelicals. Indeed, this gray area—factional self-interest posturing as gospel imperative—accounts both for the political staying power of the evangelical community as well as for the cynicism their politics so often provoke, never more so than in the era of Trump.”

Posted Essays:

- David Barr, Evangelical Support for Trump as a Moral Project: Description and Critique

- Benjamin Lynerd, On Political Theology and Religious Nationalism

- John G. Stackhouse, Jr., American Evangelical Support for Donald Trump: Mostly American, and Only Sort-of ‘Evangelical’

- Samuel Perry, A War for the Soul of American Evangelicalism

- Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, Don’t Forget Trump’s Pentecostal Fans

We invite you to join the conversation by submitting your comments and questions below.

by Benjamin Lynerd

David Barr’s underlying question could be put this way: Does evangelical support for Donald Trump stem from political theology—specifically, from the blend of Christian and classical liberal ideals that, I argue, has saturated American pulpits for centuries—or, instead, from what Samuel Perry et. al. identify as “Christian nationalism,” a raw form of identity politics that asserts the primacy of Christianity in American culture? The reality is that religious nationalism and political theology, though distinct lines of thought, overlap in significant ways among rightwing evangelicals. Indeed, this gray area—factional self-interest posturing as gospel imperative—accounts both for the political staying power of the evangelical community as well as for the cynicism their politics so often provoke, never more so than in the era of Trump.

First, some distinctions between political theology and religious nationalism: The former derives political values from theological doctrine. How to make that application is often a matter for sincere debate even among believers who share the same religious convictions. There are, of course, more and less coherent ways to apply faith to politics, which is why we should treat political theology as a serious intellectual discipline, worthy of critical engagement. Everyone brings some set of ultimate beliefs to bear on their political opinions—the only real question is how mindfully we do so.

Religious nationalism, by contrast, refers to the attempted dominance of a particular sect within society. It is the prerogative that sect undertakes to define the terms of cultural inclusion and exclusion—in this case, to own and operate the American brand. At its root, religious nationalism concerns power, whereas political theology concerns justice.

So, how have American Christians gone about merging the two? Evangelical preachers have long characterized American identity as essentially Christian. They have done so, moreover, by way of promoting what I call “republican theology,” a brand of political theology that holds to a simple dogma—that limited government can flourish only in a society with a particular moral formation, and vice versa. In this blueprint, Christianity is not a state religion, but it does define and shape the civic character so as to make the exercise of freedom possible.

So, how have American Christians gone about merging the two? Evangelical preachers have long characterized American identity as essentially Christian. They have done so, moreover, by way of promoting what I call “republican theology,” a brand of political theology that holds to a simple dogma—that limited government can flourish only in a society with a particular moral formation, and vice versa. In this blueprint, Christianity is not a state religion, but it does define and shape the civic character so as to make the exercise of freedom possible.

The boldest expressions of republican theology have depicted the American regime as an integral part of God’s redemption of the human race. Take, for example, an 1827 sermon from Lyman Beecher, a prominent itinerant and abolitionist at the height of the Second Great Awakening. The sermon revolves around a single verse in the Book of Revelation, “He that sitteth upon the throne saith, ‘Behold I make all things new’” (Rev. 21:5, King James Version), a promise most Christians interpret as Christ’s final expunging of sin, corruption, hardship, and death from the earth. Along these lines, Beecher calls it a “moral renovation which shall change the character and condition of men.” But then Beecher, marking fifty years of the American experiment, says this:

I shall submit to your consideration, at this time, some of the reasons which justify the hope, that this nation has been raised up by Providence to exert an efficient instrumentality in this work of moral renovation.

The whole sermon then morphs into a meditation on the sundry ways that the American system as designed advances the ministry of Jesus Christ in “making all things new”—by removing the landed aristocracy, by promoting “the suffrages of freemen,” by restoring the rights of conscience—in short, by creating a society free to cultivate Christian virtues (which look an awful lot like bourgeois virtues), an imperative Beecher then lays heavily upon churches and families to fulfill. Nothing short of the divine restoration of humanity is at stake in maintaining both Christian morality and the small-government ideals of the American system, a logic that resurfaces over and again in Christian discourse. 1

Those who view the American project as having eschatological significance cannot help but thread a cord through the various conditions of this prophecy, including 1) the preservation of Christian moral norms within society, 2) the curbing of government—insofar as churches, families, and virtuous citizens (particularly entrepreneurs) are shielded from the arm of the state, and 3) the assertion of America’s national sovereignty as a divine imperative. These beliefs feed off each other; they have repeatedly mobilized American Christians into political activism—against liquor, state lotteries, slavery, the League of Nations, communism, the welfare state, income taxes, public school curricula, gay rights, and Islam. Republican theology has fashioned evangelicals into a reliable bloc of voters whenever a candidate can weave its tenets into a campaign narrative, as Ronald Reagan did against the backdrop of the Cold War, as George W. Bush did after 9/11, and as Donald Trump has done against the perceived attacks by the U.S. government on Christian freedoms.

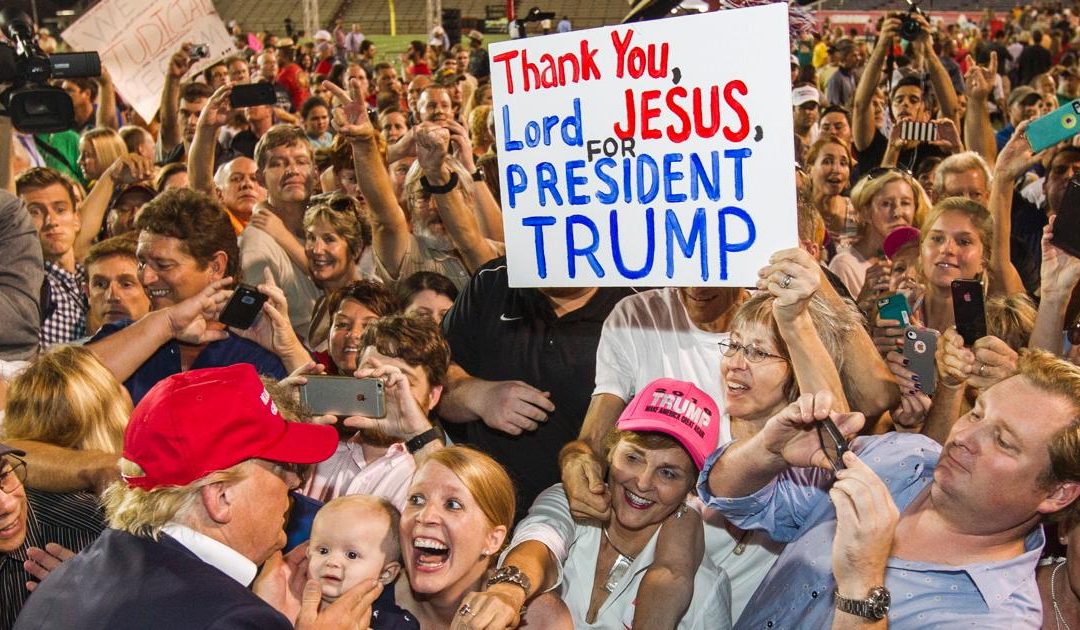

And yes, republican theology lends itself easily to the more primal impulses of Christian nationalism. Whereas the latter aspires to group empowerment within society, republican theology clothes that agenda in metahistorical logic. If the us-versus-them sentiments of Christian nationalism can be captured on a raging placard, republican theology offers a Sunday sermon to make the rage righteous. It furnishes a conceptual framework beyond factional self-interest to defend Christianity as the lodestar of American culture. It encourages Christians, even nominal Christians, to lay original claim to the national identity, and arrays them against any group or ideology that might challenge that preeminence or corrupt the nation’s ethos.

It seems clear now that Donald Trump’s guttural appeal to their sense of cultural displacement is what has drawn rightwing evangelicals so strongly into his camp, in spite of his relentless, off-camera mockery of the gospel. Evangelicals feel empowered by his rhetoric; their deeply rooted political theology simply vindicates the sensation. Clarity concerning the common good, not empowerment, is what political theology is supposed to achieve. But republican theology offers two for the price of one.

I have elsewhere discussed scriptural critiques of—and counterpoints to—republican theology. Barr’s essay offers up Reinhold Niebuhr as an author with whom Christians searching for an alternative (and even those who aren’t) would do well to become more familiar. At any rate, republican theology is not the only coherent application of the evangelical gospel to public life. It thus falls squarely upon Christian critics of this tradition to articulate and defend alternative approaches. However, if it is challenging enough to defend a religious point of view in a secular environment, it is all the more challenging when that perspective comes to be seen as mere self-interest.

Herein lies the tragedy of evangelical politics, a tragedy that the unrestrained loyalty to President Trump lays bare, but which stretches well beyond this moment in American history. Even the liberal John Rawls concedes that citizens with scrupulous theological commitments are just as entitled as everyone else to the intentional application of faith to their political views. This entitlement gets more dubious, however, rightly provoking the suspicions of others, when political theology serves merely as cover for the more pragmatic agenda of social empowerment. As Michael Gerson, a former speechwriter for George W. Bush, writes,

Who would now identify conservative Christian political engagement with the pursuit of the common good? Rather, the religious right is an interest group seeking preference and advancement from a strongman—and rewarding him with loyal acceptance of his priorities. The prophets have become clients. The priests have become acolytes.

This is not to pass judgment on the goal of empowerment as such. If we take James Madison at his word, self-empowerment is the ordinary business of every social group in America, including religious groups. There is a difference, however, between searching out the implications of the Christian gospel for politics and leveraging this gospel to advance the social position of American Christians. When evangelicals disguise the latter in the robes of the former, not only do they engage in dishonesty, but they also give fuel to the cynical view that there really is no difference—that the theological is nothing more than a cloak for the political. ♦

Benjamin Lynerd is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Christopher Newport University in Virginia. He received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Chicago. Lynerd’s book, Republican Theology: The Civil Religion of American Evangelicals, offers an historical and theological account of the hybrid position evangelicals have long affected to hold in American culture—as champions of individual liberty and as guardians of American morality. Republican Theology traces the contentious political journey of evangelicals from its earliest moments, laying bare the conceptual tensions built into their civil religion. His forthcoming work is on democratic theory and discourse ethics.

Benjamin Lynerd is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Christopher Newport University in Virginia. He received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Chicago. Lynerd’s book, Republican Theology: The Civil Religion of American Evangelicals, offers an historical and theological account of the hybrid position evangelicals have long affected to hold in American culture—as champions of individual liberty and as guardians of American morality. Republican Theology traces the contentious political journey of evangelicals from its earliest moments, laying bare the conceptual tensions built into their civil religion. His forthcoming work is on democratic theory and discourse ethics.

* Feature image: From a Trump rally at Ladd-Peebles Stadium on August 21, 2015, in Mobile, Alabama. (Mark Wallheiser | Getty Images)

- See, for example, Timothy Dwight’s Greenfield Hill (1794), Charles Grandison Finney’s “Fast Day Sermon” (1841), any of Henry Ward Beecher’s essays in his widely-circulated journal, The Christian Union (ca. 1870-93), Harold J. Ockenga’s “The Unvoiced Multitudes” (1942), Billy Graham’s “We Need Revival” (1949), and Os Guinness’s A Free People’s Suicide: Sustainable Freedom and the American Future (2012). ↩