The Issue

This year has brought a reawakening and amplification of social awareness on gender-related issues in the public sphere. Inspired by the voices of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, the May-June issue of the Forum takes up the question of how scholars whose research informs discourses about religion can uniquely contribute to extending an awareness of these issues through their scholarship and teaching. Using the resources available in the academic study of religion, contributors to this issue reflect outwards considering how their scholarly work is informed and transformed by movements like #MeToo, along with the various ways in which they hope this work can contribute to the wider conversation on gender, consent, and power dynamics.

The Forum was thrilled to collaborate with the Divinity School Women’s Caucus in putting this issue together. Allison Kanner (PhD student at the Divinity School and coordinator of the Women’s Caucus) and Anna Lee White (MA student at the Divinity School and Women’s Caucus representative) served as guest editors for this month’s issue. Throughout the month, scholars contributed diverse essays on the theme of gender and religion in the wake of #MeToo and #TimesUp. Professor Sarah Hammerschlag closed out the roundtable with a response. We invite you to join the conversation by submitting your questions and comments.

Published Essays:

- Rachel Schine (University of Chicago), Textual Harassment: Reading Medieval Arabic Love Verse in the Context of Consent

- Elizabeth Brocious (University of Chicago), #MeToo and Discourses of Love: A Mormon Case Study

- Samuel Catlin (University of Chicago), The Will to Ignorance: #MeToo as Pedagogical Crisis

- Response by Sarah Hammerschlag (University of Chicago), #TimesUp and the Myth of Neutral Space

Abstract

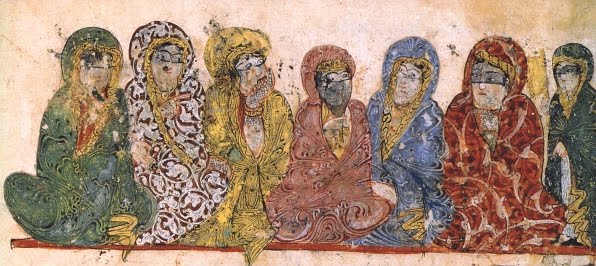

In her essay, “Textual Harassment: Reading Medieval Arabic Love Verse in the Context of Consent,” Rachel Schine (University of Chicago) looks at the differences between the speakers and objects of adoration in the poetic genre of mannered love verse (ghazal). Addressing the inequalities of participation in the medieval Arabic literary playing field, Rachel discusses the works of the Umayyad-era poet ‘Umar b. Abī Rabī‘a in light of an anecdote regarding his behavior in the fictional Arabic popular epic, Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, where the caliph’s daughter intentionally secludes herself to avoid becoming an unwilling subject of his poetry. Through analyzing this anecdote, Rachel problematizes a paradigm that any evidence of women in pre-modern sources should be valued, and instead prompts us to think about the role of consent in such works and our reception of them as contemporary readers in the aftermath of #MeToo and #TimesUp. She argues that women’s absences from certain literary and social domains can be read not only as a form of patriarchal exclusion but as an agentive gesture of denying consent.

by Rachel Schine

In “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Hélène Cixous declares that woman must write herself, saying,

A woman’s body, with its thousand and one thresholds of ardor—once, by smashing yokes and censors, she lets it articulate the profusion of meanings that run through it in every direction—will make the old single-grooved mother tongue reverberate with more than one language.1

Though in this assertion there lurks an intimation of just who is supposed to seize upon écriture féminine and write herself—the stifled, continental woman within whom lies a tantalizingly Orientalized sexuality, adumbrated through the evocation of the French title of the Arabian Nights (Les mille et une nuits)—Cixous nonetheless raises the trenchant point that women and their bodies are routinely failed by men’s literary representations of them. Often, when Cixous’s call is projected onto history, it is through the excavation and reclamation of “lost” women’s writing that reaches beyond the male-dominated canon, or, failing that, through representations of women in men’s writing that may be read against the grain. Such projects of recovery have conveyed many women’s writings in medieval Arabic to contemporary Western scholars, from the pre-Islamic laments of Khansā’ to the esoteric Sufi writings of ‘Ā‘isha al-Bā‘ūniyya. There also exists a wealth of male-authored literature in which women are depicted, with these items sometimes being the sole sources we have on women and gender relations for large patches of medieval Islamic history.

The possibility that a comparatively vast quantity of accounts by and of women may have been lost to the sands of time is typically viewed as a great loss. A question not often asked, though, is whether a woman’s absence might be by her own design—whether, forsaken and victimized by men and their language, a woman would have cause to be the agent of her own exclusion from a body of text. Here, I present an anecdote from the twelfth-century Arabic popular epic, Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, in which a noblewoman meets the notorious Umayyad-era love poet, ‘Umar b. Abī Rabī‘a, on the ḥajj pilgrimage and obscures herself from view throughout the journey so that she won’t be made a subject of his ardent poems against her will. This scene troubles our prevailing notion that any kind of literary representation of medieval women is better than nothing at all. Moreover, it prompts us to consider whether certain types of literary representation may actually have been a form of harassment and an instrument for disciplining women and their movements, such that choosing not to be represented becomes an act of resistance in itself, an intentionally tacit declaration that #TimesUp.

The possibility that a comparatively vast quantity of accounts by and of women may have been lost to the sands of time is typically viewed as a great loss. A question not often asked, though, is whether a woman’s absence might be by her own design—whether, forsaken and victimized by men and their language, a woman would have cause to be the agent of her own exclusion from a body of text. Here, I present an anecdote from the twelfth-century Arabic popular epic, Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, in which a noblewoman meets the notorious Umayyad-era love poet, ‘Umar b. Abī Rabī‘a, on the ḥajj pilgrimage and obscures herself from view throughout the journey so that she won’t be made a subject of his ardent poems against her will. This scene troubles our prevailing notion that any kind of literary representation of medieval women is better than nothing at all. Moreover, it prompts us to consider whether certain types of literary representation may actually have been a form of harassment and an instrument for disciplining women and their movements, such that choosing not to be represented becomes an act of resistance in itself, an intentionally tacit declaration that #TimesUp.

Before diving into the anecdote, a few words should be said about ‘Umar b. Abī Rabī‘a (d. 719 CE). ‘Umar’s large oeuvre is mainly devoted to an intimate brand of ghazal, or love poem, distinguished by its physicality from the more chaste, star-crossed yarns of many of his contemporaries.2 Most of the women he elegizes are noble, some of them are named, and many of them are spoken for, in that he often reconstructs dialogue with his lovers in his poems. Not only does this literary artifice create a sense of closer proximity with the beloved, but it draws the tone of the poem toward the earthly idiom of everyday conversation. This particular quality contrasts with a common later use of the ghazal form to elegize a heavenly (i.e. non-corporeal) beloved—present in much Sufi discourse. Moreover, in the case of the chaste love of some of the form’s most famous early exponents (Majnūn Layla, Jamīl Buthayna, etc.), the ghazal becomes a means to emphasize the physical distance from one’s beloved, which in turn transforms the lover’s plight into one of profound asceticism and spiritual longing. Imagined exchanges like the following are scattered throughout ‘Umar’ collection,

She said to the fine companions in her midst,

White-faced virgins, like dolls,

“By God, Lord of Muhammad, tell me truly,

Are you all pleased by this youth who’s [broken] in?

The house was well-secured,

[and he arrives] without an appointment.Does he not fear ruin?”So I answered her, “Truly the beloved is destined to an audienceWith whomever he desires, even if he fears hostility”My mind was eased when I slept with themAnd I slipped away from her where I’d had a brush with loveShe was white like the sun when it shines,

Marked by beauty, astonishing to the beholder3

Or, in a poem about a woman whom he meets on a desert journey,

She said to her slave girl, “Look at that, who’s the first one?

And pray, who is the rider of the dark brown camel?”

She replied, “[‘Umar], I know his garb,

And his mount, it is clearly none other.”

She said, “And is he–?” She said, “Yes, so take joy

In him who seeks a rendezvous” […]

When we stopped and drew near the two of them,

She responded to our approach with coyness

They said, “Rest, then repair to your mounts

Under cover, concealing him from the slave women.” […]

In the first excerpt, ‘Umar blurs the line between one woman and many, discussing his beloved’s mute maids who serve as a sounding board for his lover’s misgivings and then saying “I slept with them,” implying the whole retinue joined in, yet he concludes with a line about a single lover. In the second excerpt, he conjures up a backstage conversation in which a servant coaxes her mistress into their secret tryst. Both passages give the impression of a general feminine collusion around ‘Umar being able to get what he wants.

Perhaps the most controversial feature of ‘Umar’s work is his risqué poetry about women he meets while on religious pilgrimage.4 It is little wonder, then, that in the fictive vignette in Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, when the caliph ‘Abd al-Malik’s daughter, Marwah, finds out that ‘Umar has joined her ḥajj caravan, she goes to extremes to avoid him,

[T]he mistress Marwah […] was departing for the Hijaz that very year […] and there left along with their group a poet by the name of ‘Umar b. Abī Rabī‘a. […] Marwah had heard in Damascus that in his poetry he subjected wealthy women to mention and described their charms in verse. Yet she did not learn that he was with her making pilgrimage until they had passed the halfway point. […] She grew regretful over [the situation] she had wrought and took to hiding herself in her howdah to the extent that even the women could not see her— all of this was out of fear that the poet would see her, because she was from a people of extreme goodness and upstanding beauty, characterized by faith, soundness, and honorable lineage, and by chastity and self-restraint.Marwah did not cease [hiding herself] until she had completed the ḥajj and the ‘umrah and given alms to the poor and the ailing and clothed the widows and the outcasts. She determined to remain in Mecca until [other pilgrims] had arrived […] and the poet had set out with them to his country, saying, “I will depart with my slaves and servants and be alone, all by myself, with my manservants and maids.” […] All of this was out of fear of her exposure by the poet, that he might cause her name to be on the tongues of the people.5

The authors of the popular epic Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma are now unknown to us. Indeed, the composition of such works was likely collectivized, accruing material over countless recitations and several centuries. Modern anthropological studies indicate that, at least in the recent past, the recitation traditions around these texts have been almost exclusively the purview of men, and this is also supported by the names of reciters listed in various versions of the stories.6 Thus, we could read the above scene as a paternalistic warning: the ideal, modest woman will avoid becoming the subject of men’s lustful gaze—and by extension their poetry—and devote herself to personal piety. To read it this way, though, seems to re-inscribe the voyeurism that our heroine is trying to avoid by interpolating an omniscient, moralizing male author as the inventor of this vignette.

I would like to suggest instead that we take the epic’s anonymity as an opportunity to democratize the text for ourselves, and to read it in terms of the female character’s wishes and message. If we do so, a much simpler, more tangible story emerges: an eminent (lest we forget that class matters here) woman wants to be able to perform her ritual observances freely, but is beleaguered by a lecherous artist, whose poetic talents have earned him the public ear. In her view, his literary production would come at a great social cost to her, and this cost is couched in terms of exposure (‘-r-ḍ), or the engendering of vulnerability through the violation of one’s privacy. Moreover, probing a bit deeper into the nature of women’s literary production in this era, ‘Umar’s selection of subject belies a predatory calculus: love poetry for much of the early medieval period was considered the purview of men and slave courtesans, while noblewomen were largely restricted to the genre of lament.7 Writing one’s own love story as a high-born woman, or counter-writing against another’s amorous expressions, was itself a socially precarious maneuver. ‘Umar has cornered Marwah into what we may now recognize as an all-too-common double bind, in which a woman’s speech and her silence in the face of harassment are both potentially incriminating for her.

How many women who ended up elegized in verse might have experienced Marwah’s plight? How often have women been (mis)represented in literature without their consent? When we read such literature, are we perpetuating this violation? Rather than being compelled to abandon these texts altogether, we can look to the language of “callout” and “consent” that has been instrumental to movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp to furnish us with tools for reading such works more consciously—to receive unilaterally expressed “love” and lust with skepticism, to hold the ‘Umar’s of the world to account—and can moreover place this in conversation with the already emergent discourses around these issues contained in much earlier works. And, perhaps, we can also grow to better appreciate the dimensions of a woman’s absence in certain spaces as a product not only of patriarchal exclusion, but of a rebellion against forms of inclusion that are ugly and incomplete. ♦

Rachel Schine is a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, focusing on pre-modern Arabic literature, with comparative interests in Judeo-Arabic and Persian. Her research focuses include orality and storytelling practices, gender/sexuality and race/race-making in pre-modern works, popular narrative, and popular exegesis and prophetology. Her dissertation analyzes black heroes and their figuration in the popular sīrahs, a body of medieval legendary conquest literature, and is tentatively titled, “On Blackness in Arabic Popular Literature: The Black Heroes of the Siyar Sha‘biyya, their Conception, Contests, and Contexts.”

Rachel Schine is a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, focusing on pre-modern Arabic literature, with comparative interests in Judeo-Arabic and Persian. Her research focuses include orality and storytelling practices, gender/sexuality and race/race-making in pre-modern works, popular narrative, and popular exegesis and prophetology. Her dissertation analyzes black heroes and their figuration in the popular sīrahs, a body of medieval legendary conquest literature, and is tentatively titled, “On Blackness in Arabic Popular Literature: The Black Heroes of the Siyar Sha‘biyya, their Conception, Contests, and Contexts.”

Guest Editors

Allison Kanner is a Ph.D. student in Islamic Studies at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Her research focuses on intersections between medieval Islamicate romance literature, mystical literature, and gender and sexuality in Religious Studies. She currently leads the Women’s Caucus, a student-founded club at the Divinity School, as well as a weekly Persian language conversation group.

Allison Kanner is a Ph.D. student in Islamic Studies at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Her research focuses on intersections between medieval Islamicate romance literature, mystical literature, and gender and sexuality in Religious Studies. She currently leads the Women’s Caucus, a student-founded club at the Divinity School, as well as a weekly Persian language conversation group.

Anna Lee White is an MA student in History of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Her studies focuses on the history of South Asian religious literature. She plans to pursue research on devotional poetry and hagiographies from early-modern North India during a PhD at McGill University. She is also a member of the Divinity School Women’s Caucus.

Anna Lee White is an MA student in History of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Her studies focuses on the history of South Asian religious literature. She plans to pursue research on devotional poetry and hagiographies from early-modern North India during a PhD at McGill University. She is also a member of the Divinity School Women’s Caucus.

- H. Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Keith & Paula Cohen trans., Signs1 (1976): 885. ↩

- For more, see: J.E. Montgomery, “‘Umar (b. ‘Abdallāh) b. Abī Rabī‘a,” in Encyclopedia of Islam II, P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, eds. Accessed 27 April 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7708 ↩

- All translations are my own. For the curious, the entirety of ‘Umar’s dīwān can be found here: https://ia800508.us.archive.org/23/items/diwan_omar_ibn_abi_rabiaa/diwan_omar_ibn_abi_rabiaa.pdf ↩

- This supposedly earned ‘Umar censure from the caliph ‘Umar b. ‘Abd al-Azīz. For more on this, see: R. Irwin, Night & Horses & the Desert: An Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature (Woodstock: Overlook Press, 2000), 58. ↩

- This excerpt is from the second part (juz’) of the 1909 Cairo print edition of Sīrat Dhāt al-Himma, p. 48-49. The sīrahas, sadly, not been translated in full, but there is a forthcoming abridgment of it by Melanie Magidow, whose website features some choice excerpts and an exposition on the history and importance of the epic: http://www.melaniemagidow.com/2016/08/25/nea-grant-recipient/ ↩

- Perhaps the most significant ethnography of the performance of Arabic epics is: Dwight Reynolds Heroic Poets, Poetic Heroes: The Ethnography of Performance in an Arabic Oral Epic Tradition (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1995). ↩

- On this, see: T. Qutbuddin, “Women Poets,” in Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia vol. 1, J.W. Meri, ed. (New York: Routledge, 2006), 865-867. ↩