“The Heathen Chinee” is a poem by Bret Harte that satirizes Irish laborers’ prejudice against Chinese workers in northern California. Despite these origins, it was used to claim that white American masculinity was superior to Chinese masculinity. To explore how “The Heathen Chinee” was used for its two opposing messages, I will be looking at the poem as a text and its book form as an object. Specifically, the poem and book’s physicality, context, and story explain their importance for creating American ideals of race and gender in the late 1800’s.

(Credit: University of Chicago Special Collections)

The physical qualities of this 1871 edition reflect the book’s production for a general American audience. The pages are made from wove paper, the string binding is stab-sewn, and the orange cover is glued on (Figures 1-2). Though technologically advanced, these cheap materials and techniques indicate that the book was intended to be affordable for the public. In addition, the dimensions of 4.5 by 7 inches and heavy length-wise crease signal that it was folded to be portable (Figure 3).

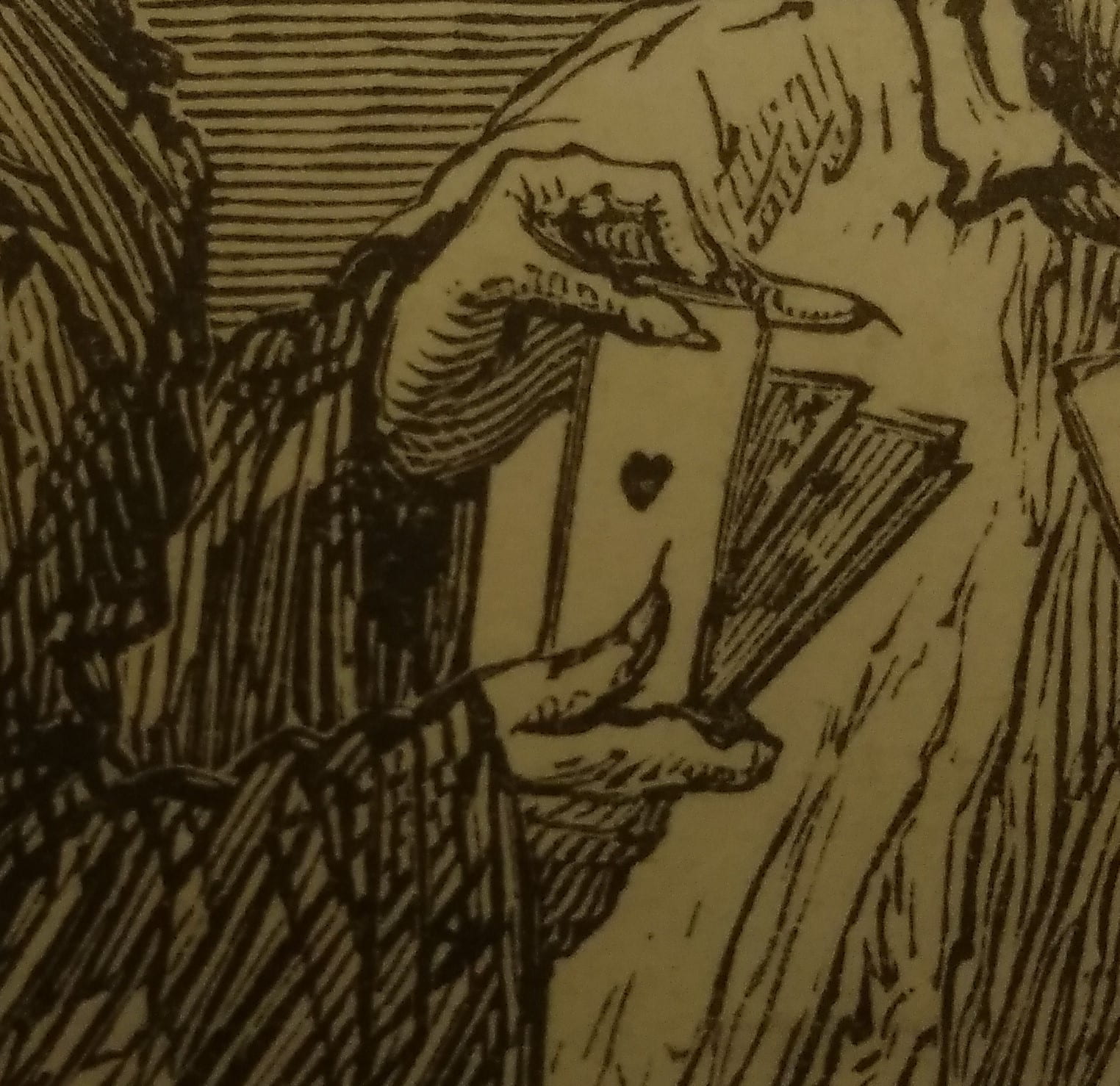

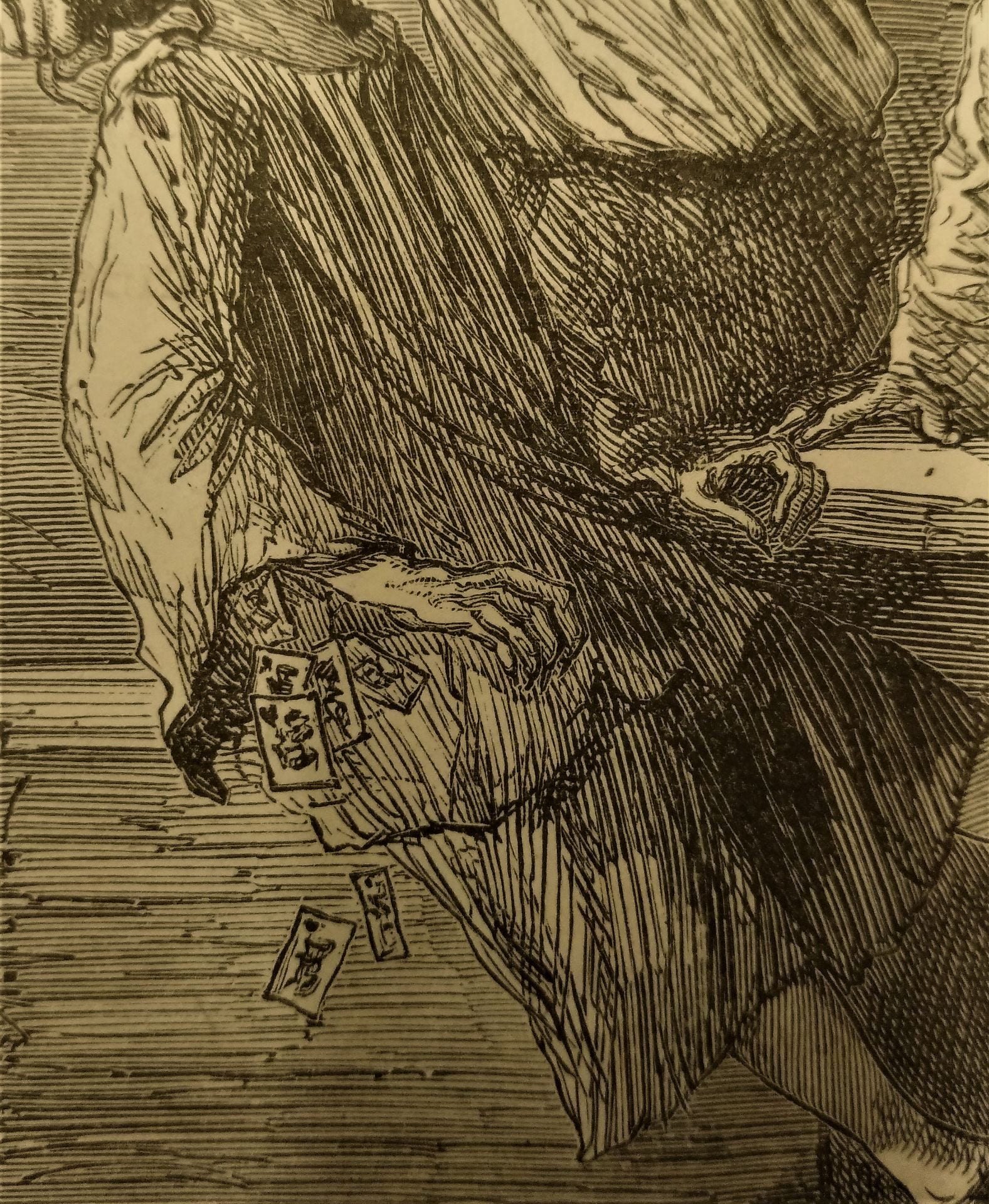

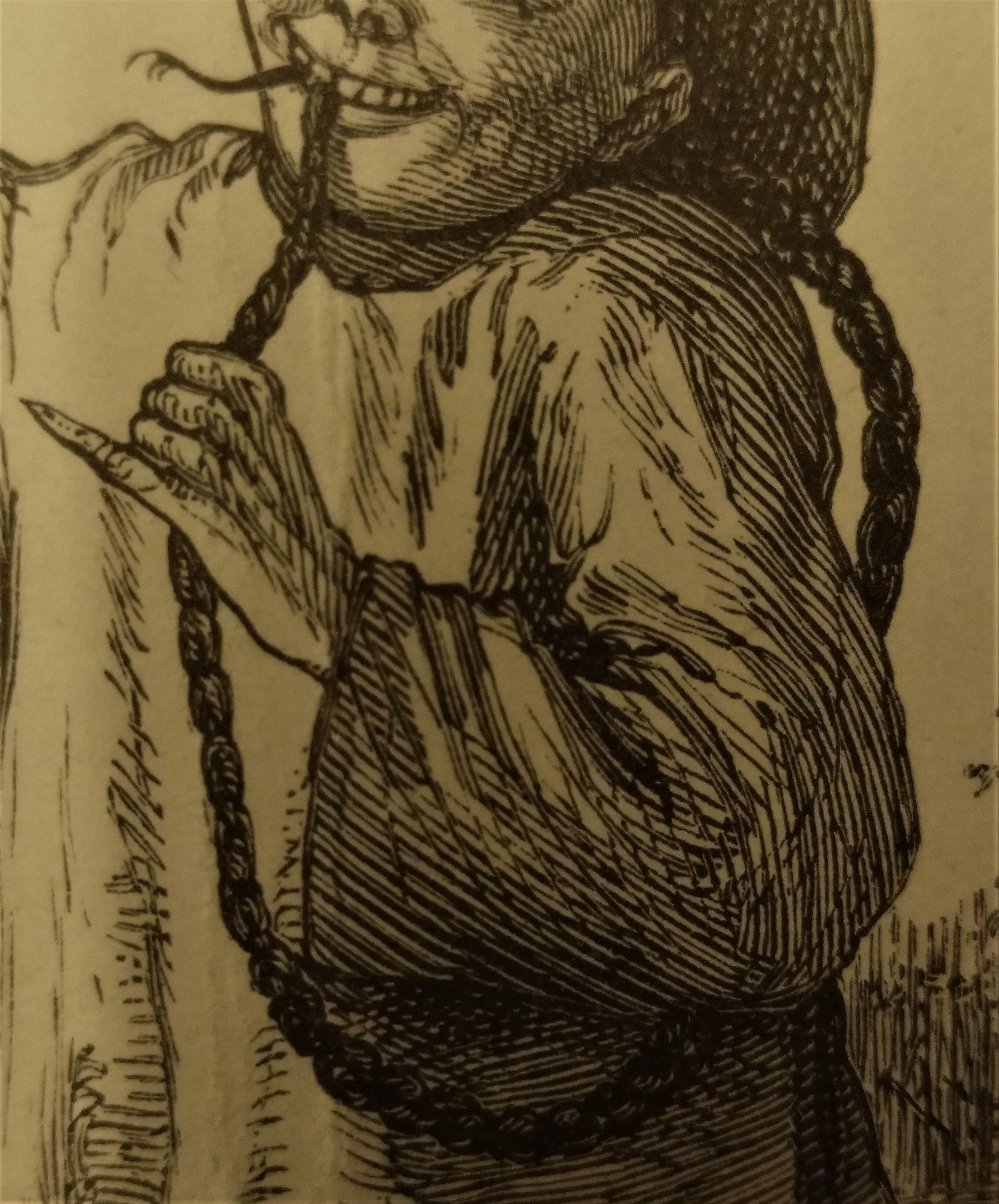

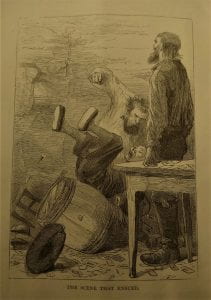

As shown in its pictures, “The Heathen Chinee” was read as an anti-Chinese piece praising white American males. S. Eytinge Jr. depicts the “Oriental” Ah Sin as exotic, bestial, and feminine: he has narrow eyes, a straw hat, long fingernails, flowing clothing, and a queue (long braid) (Figures 4-7). Interestingly, Bill Nye is not drawn as fully noble. He grabs Ah Sin by the hair and punches him while the latter cannot defend himself (Figures 8-9). However, he dominates in the end and sits on his victim’s unconscious body (Figure 10). The illustrator thus provides a threatening yet defeated Chinese caricature to support the “higher” status of white American men.

“The Heathen Chinee” is entwined with the backlash against Chinese immigration during the late 1800’s. Characterized by violent attacks and racist laws, this movement began in California, as white Americans moved west from the East Coast. This led to resentment over “mass unemployment and ruthless competition for jobs … Chinese [laborers were] … usually willing to work longer hours for less than half the pay … [and were used as] strike-breakers.”[1] However, during the 1870’s, the motive for hatred switched to the belief that Chinese people were racially inferior. White Americans also believed that they were “incapable of attaining the state of civilization of Caucasians,” or could not assimilate into American society.[2] Eventually, the turmoil gave rise to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This banned Chinese workers from entering the United States for ten years.[3]

The author’s background further reveals his intended message about the irony of anti-Chinese prejudice. Bret Harte is best known for his short stories about the American West. However, he was actually a “transitional figure” in American literature.[4] Even though his most famous works were “in the 19th-century sentimental tradition[,] aspects of his writings [featured] parody and social protest [from] the realist school.”[5] Originally published as “Plain Language from Truthful James,” “The Heathen Chinee” thrust Harte into the national spotlight. The poem was used to support the anti-Chinese movement and produced in books, playing cards, pitchers, and more.

Knowing Harte’s background in satire uncovers the storyline’s social critique. While playing the card game Euchre, the white narrator, James, notices his friend, Bill Nye, cheating. Both believe that the Chinese character, Ah Sin, naïvely does not know the rules. They are shocked when they find out Ah Sin has also been cheating. Enraged, Bill states, “We are ruined by Chinese cheap labor,” as he assaults him.[6] By stressing Bill’s hypocrisy, Harte aimed to “satirize anti-Chinese prejudices pervasive in northern California among Irish day-laborers.”[7] Although the Irish mistreated the Chinese, as members of the working class, both were looked down upon. However, this satire was not successfully conveyed due to the lack of clarity. Instead, Harte’s message opposes Eytinge’s pictures and the book’s construction.

By studying “The Heathen Chinee” as an object, we can track how it presented a “lower” Chinese “Other” to lift up a white American masculinity. To do this, the former was shown as dangerous and strange, represented by the animalistic, feminine Ah Sin. The latter was depicted as imperfect yet desirable. In contrast though, the poem expresses a satirical message against anti-Chinese racism. Thus, there is ambiguity in how the poem’s contents contradict the book’s physical traits. Ultimately, “The Heathen Chinee” demonstrates how an object’s meaning can unexpectedly get warped as it becomes popular.

[1] Iris Huang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York: Viking, 2003), 117-118.

[2] Peter Kwong and Dušanka Miščević, Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest Community (New York: The New Press, 2005), 95.

[3] “Transcript of Chinese Exclusion Act (1882),” Our Documents, National History Day, The National Archives and Records Administration, and USA Freedom Corps, accessed February 27, 2020, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=47&page=transcript.

[4] Patrick Morrow, “Bret Harte (1836-1902),” American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 3, no. 2 (1970): 167, accessed February 27, 2020, www.jstor.org/stable/27747705.

[5] Morrow, 167.

[6] Bret Harte, The Heathen Chinee (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1871): 15.

[7] Gary Scharnhorst, ““Ways That Are Dark”: Appropriations of Bret Harte’s “Plain Language from Truthful James”,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 51, no. 3 (1996): 378, accessed February 24, 2020, doi:10.2307/2934016.

Bibliography

Harte, Bret. The Heathen Chinee. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1871.

Huang, Iris. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York: Viking, 2003.

Kwong, Peter, and Dušanka Miščević. Chinese America: The Untold Story of America’s Oldest Community. New York: The New Press, 2005.

Morrow, Patrick. “Bret Harte (1836-1902).” American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 3, no. 2 (1970): 167-77. Accessed February 27, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/27747705.

Scharnhorst, Gary. ““Ways That Are Dark”: Appropriations of Bret Harte’s “Plain Language from Truthful James”.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 51, no. 3 (1996): 377-99. Accessed February 24, 2020. doi:10.2307/2934016.

“Transcript of Chinese Exclusion Act (1882).” Our Documents. National History Day, The National Archives and Records Administration, and USA Freedom Corps. Accessed February 27, 2020. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=47&page=transcript.

One thought on “Counternarratives: The Heathen Chinee”