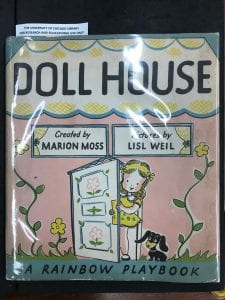

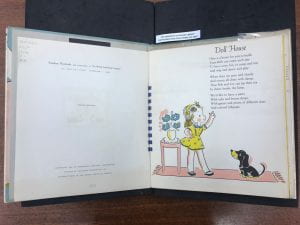

Doll House, a children’s book that converts into a paper house, was written by Marion Moss and illustrated by Lisl Weil (Fig. 1). It was published in 1946 by the World Publishing Company, and was part of the Rainbow Playbook series. Originally sold for $1.00, the book folds out into four rooms. From its pages, users can punch out paper dolls, furniture, and objects. Analyzing Doll House as both a book and a toy sheds light on American society and manufacturing after World War II. Young white girls likely used Doll House to imagine themselves as miniature homemakers and postwar consumers. Yet, these girls may have exercised limited agency within the space provided by Doll House.

In the late 1940s, postwar wealth and privileges provided by the G.I. Bill contributed to what American historian Lizabeth Cohen calls the “Consumers’ Republic.” [1] This period included a “new postwar ideal of the purchaser as citizen who simultaneously fulfilled personal desire and civic obligation by consuming.” [2] Specifically, “house construction provided the bedrock of the postwar mass consumption economy . . . through turning ‘home’ into an expensive commodity for purchase by many more consumers than ever before.” [3] But, racism within state agencies prevented black and working-class veterans from accessing mortgage loans. This contributed to “homogeneous suburbs occupying distinctive rungs in a clear status hierarchy of communities.” [4] Doll House displays this transformation; it reflects white home ownership and the growing middle class. The book features an all-white cast of children. It shows a front lawn and car parked outside a nearby home, resembling the white suburban ideal Cohen describes (Fig. 2). Doll House also highlights a shift in American industry. When toy manufacturing began during the 1900s, it occurred on a small scale. [5] Most people still made their own toys at home. During the war, the government encouraged home production to preserve materials needed for combat. The book’s semi-finished state compels its user to build the actual dollhouse themselves. As both a manufactured book and partially home-produced toy, Doll House represents the transition in American manufacturing from home production to mass production.

By emphasizing cooking and cleaning, Doll House shows that proper female behavior comes from successful performance of household tasks. The main character in Doll House is Lee, a young girl who brings the reader through the house. She takes the audience into the kitchen, where text reads “the kitchen where we’ll cook our food is yellow, blue and white with jars of jams, and pots and pans that shine so neat and bright.” (Fig. 3) [6] On the other hand, in Fire House and Wild West (1949 and 1950), two fold-out books published in the same Rainbow Playbook series, the target audience is male. [7] Neither book has dolls similar to those in Doll House. Instead, both books have cowboys on horses and firemen drawn in dynamic motion and bright colors (Fig 4 and 5). While Doll House restrains its female demographic, other children’s books from the late-1940s targeted at boys praise physical strength and intelligence.

Doll House invites young users to build a home and fill it with items. In the kitchen and bedroom, empty shelves must be filled with dishes and toys. Since there are no instructions, the book was meant for use by a child and her mother. In this way, it strengthens the connection between the adult consumer and the future one. While the pastel-colored rooms appeal to children, the lack of adults causes main characters Bob and Lee to imitate miniature parents. Outside of organizing Sue’s birthday party, Moss writes that “Bob and Lee can sip their tea / In chairs beside the lamp.” [8] These children are not the house’s owners and after they leave Sue’s party, the book’s user can imagine herself as the homeowner and homemaker. At the same time, girls paging through Doll House likely identified with Lee’s homemaking responsibilities, and her protagonist status. As a result of the drawings that show her confidently beckoning to readers, Lee is clearly the main character in the text while Bob remains a supporting character (Fig. 6). In this way, Doll House displays a female-dominated world, in which male control falls away.

[1] Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003), 119.

[2] Ibid, 119.

[3] Ibid, 122.

[4] Ibid, 202.

[5] Christopher Byrne, A Profile Of The United States Toy Industry, 2.

[6] Marion Moss and Lisl Weil, Doll House (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1946).

[7] Leo Manso, Fire House and Wild West (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1949 and 1950).

[8] Marion Moss and Lisl Weil, Doll House (Cleveland: World Publishing Company, 1946).