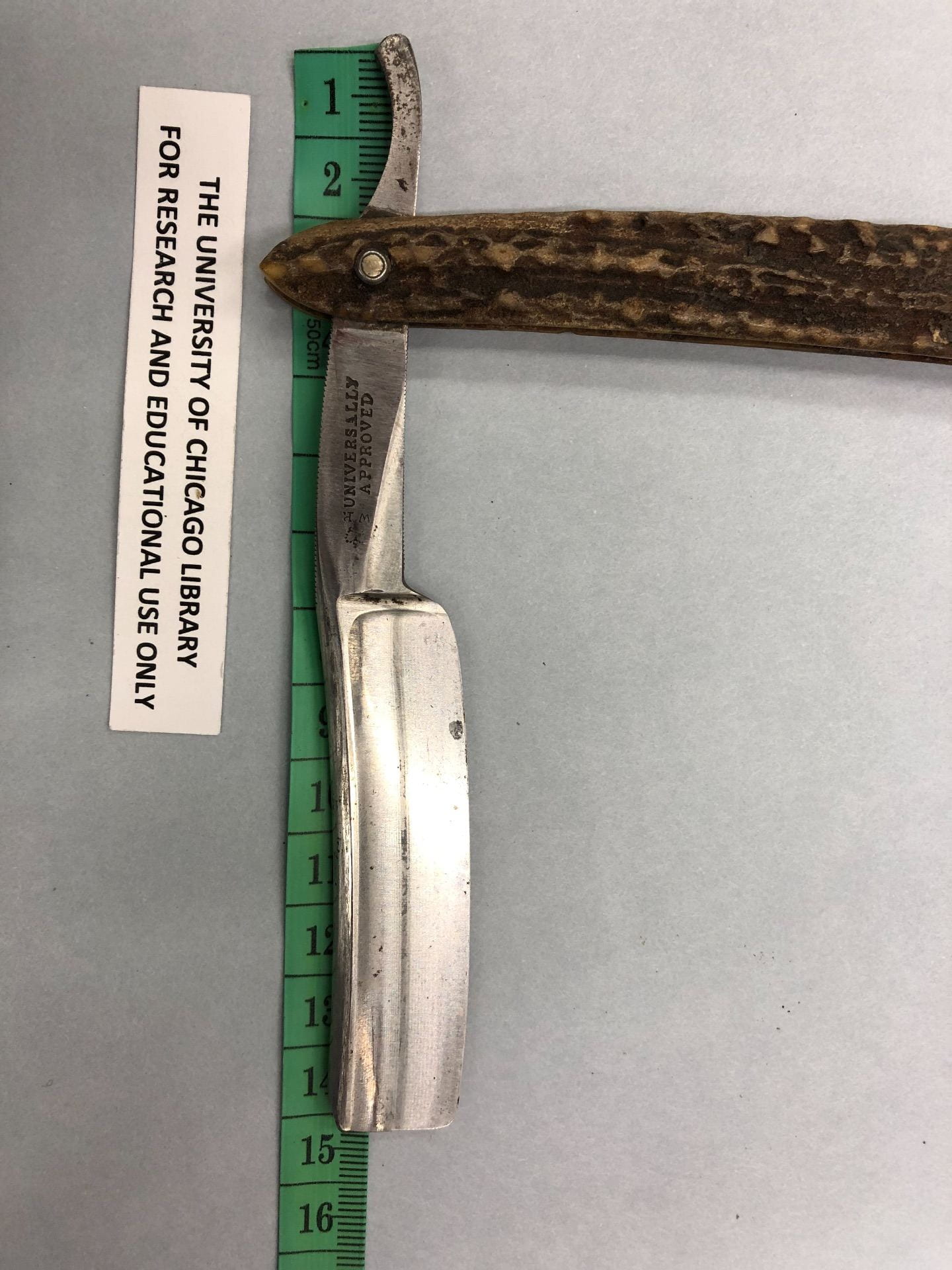

Straight razors have a use, but society even influences these objects. From the material of the handle to the design, the razor itself takes ideas in culture and turns them physical attributes. The razor’s handle is made from bone, which adds an element of death. When opening and closing the razor, you have to hold the bone and that serves as a reminder that an animal died. Men were sold this straight razor solidifying the idea that men should handle death. The design of the razor also furthers the idea that men should inflict violence due to the contrast of the blade and handle. Since the blade is sharp and can cause harm, the act of folding the blade into the handle serves to violate the animal by reenacting the cutting of bone. Forcing someone to perform an act of violence enforces cultural ideas of masculinity as tied to dominance and power.

Men were sold this straight razor solidifying the idea that men should handle death. The design of the razor also furthers the idea that men should inflict violence due to the contrast of the blade and handle. Since the blade is sharp and can cause harm, the act of folding the blade into the handle serves to violate the animal by reenacting the cutting of bone. Forcing someone to perform an act of violence enforces cultural ideas of masculinity as tied to dominance and power.

There is a faint engraving on the blade of a crown and the initials “WR.” These markings are consistent with other razors made in England during William IV’s Reign from 1830 to 1837 [1].  Around this time, ivory and tortoiseshell were more expensive than wood [2]. This indicates bone handles, even less common, likely fetched a higher price. This serves to solidify how wealth can facilitate masculinity.

Around this time, ivory and tortoiseshell were more expensive than wood [2]. This indicates bone handles, even less common, likely fetched a higher price. This serves to solidify how wealth can facilitate masculinity.

Interestingly, the box comes from the tristate area and dates after the razor. The box reads: “FRIEDMANN&LAUTERJUNG’S ELECTRIC RAZOR $2.50” referring to a company formed in 1866 [3]. This means that the case was added after William Beaumont’s purchase and death, likely by his son Israel and preserved by his grandson Ethan. By keeping the razor in this case, it elevates the culture of the past on a pedestal. This additional cover keeps people from randomly viewing the razor, excluding people, and making its usage a ritual. The box was added when disposable razors were increasing in popularity. This is important because the straight razors durability lets the box protect and preserve masculinity in one object through the generations.

This means that the case was added after William Beaumont’s purchase and death, likely by his son Israel and preserved by his grandson Ethan. By keeping the razor in this case, it elevates the culture of the past on a pedestal. This additional cover keeps people from randomly viewing the razor, excluding people, and making its usage a ritual. The box was added when disposable razors were increasing in popularity. This is important because the straight razors durability lets the box protect and preserve masculinity in one object through the generations.

Over the course of this razors use, men’s facial hair came into fashion. Key figures such as David Thoreau and Abraham Lincoln wore facial hair as ways to connect with the physical world [4]. Through the construction of the beard relating to earthly men, the church looked unfavorably on beards within their ranks [5]. William Beaumont’s photos and pictures document him to have no facial hair making him connected to power of the unnatural. As a surgeon, this presentation made him appear more knowledgeable. This indicates that Beaumont regularly used his razor to construct his presentation, making the razor an object to claim a higher ground and give himself authority.

William Beaumont’s photos and pictures document him to have no facial hair making him connected to power of the unnatural. As a surgeon, this presentation made him appear more knowledgeable. This indicates that Beaumont regularly used his razor to construct his presentation, making the razor an object to claim a higher ground and give himself authority.

By buying the razor, Beaumont reclaimed the act of shaving and lessened the influence of barbers. Through the 1800s, black men opened barbershops to gain monetary freedom. Even though some did, the power dynamics between a white client and black worker stayed the same. This changed when white people started to fear black men. White men grew beards or shaved themselves such that black men were pushed out of barbershops [6]. This change is represented in movies where white men were in control in Scenes in a Barbershop and The Dull Razor. At the same time, films showed black men fighting with razors in A Night in Blackville [7]. Beaumont’s purchase thus contributed to the discriminatory fear.

Theories of evolution lead to hair growth becoming an area of study with value judgments on who should have hair [8]. This construction excluded non-men who have facial hair and classified them as sexual inversions [9]. Circus acts, performers, and mummification objectified bearded women [10]. Razors were not marketed to women because they remove hair temporarily. Instead, companies advertised chemical alternatives in magazines to permanently remove “this great disfigurement of female beauty” [11]. This phrasing demonstrates a conflict between facial hair and femininity. While women and men were sold different methods for facial hair removal, women did use razors [12]. In Easy Shaving: A Farce in One Act, a woman barber helps to disguise another woman through ‘men’s’ clothing and shaving her [13]. As a farce, the writers demonstrate how the act of shaving a woman that does not need to shave is funny.

White men constructed both the razor itself and the culture around its use. White men othered along racial and gendered lines, evident in how razors were depicted in other medium. While the culture surrounding the razor changed as it was passed down, this straight razor maintained its association with masculinity and whiteness.

[1] Frederick E.Atwood, Antiques A Monthly Magazine for Collectors & Amateurs (Boston: Frederick E. Atwood, 1922), 263.

[2] Benjamin Kingsbury, A Treatise On Razors: In Which the Weight, Shape, and Temper of a Razor, the Means of Keeping It in Order, and the Manner of Using It, Are Particularly Considered; and in Which It Is Intended to Convey a Knowledge of All That Is Necessary On This Subject (8th ed. London: Printed by Kerwood and Cox, 1820), 48.

[3] Robert K. Waits, Before Gillette: The Quest for a Safe Razor : Inventors and Patents, 1762-1901 (Raleigh, NC: Lulu Enterprises, Inc., 2009), 88.

[4] Reginald Reynolds, Beards: Their Social Standing, Religious Involvements, Decorative Possibilities, and Value in Offence and Defence Through the Ages (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976), 270, 280.

[5] Ibid, 285-287.

[6] Douglas Walter Bristol, Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 175.

[7] Selig Polyscope Company, 1907 Catalogue of The Selig Polyscope and Library of Selig Films (Chicago, IL: The Selig Polyscope Co., Inc. 1907), 71, 74, 75.

[8] Rebecca M. Herzig, Plucked: A History of Hair Removal (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 56-57

[9] Ibid, 71.

[10] Ibid, 64. Allan D. Peterkin, One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.), 102-105.

[11] “Atkinson’s Depilatory,” Liberator, (October 23, 1840), 171.

[12] Allan D. Peterkin, One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.), 103.

[13] Francis Cowley Burnand and Montagu Stephen Williams, Easy Shaving: A Farce in One Act. (London ; New York (122 Nassau St.): S. French, 1872), 11.

Bibliography

“Atkinson’s Depilatory,” Liberator, October 23, 1840.

Atwood, Frederick E. Antiques A Monthly Magazine for Collectors & Amateurs. Boston: Frederick E. Atwood, 1922.

Bristol, Douglas Walter. Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Burnand, F. C. (Francis Cowley), and Montagu Stephen Williams. Easy Shaving: A Farce in One Act. London ; New York (122 Nassau St.): S. French, 1872.

Butters, Gerald R. Black Manhood On the Silent Screen. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002.

Carter, William. Rhythmical Essays On the Beard Question. London: Simpkin, Marshall, 1868.

Herzig, Rebecca M. Plucked: A History of Hair Removal. New York: New York University Press, 2015.

Kingsbury, Benjamin. A Treatise On Razors: In Which the Weight, Shape, and Temper of a Razor, the Means of Keeping It in Order, and the Manner of Using It, Are Particularly Considered; and in Which It Is Intended to Convey a Knowledge of All That Is Necessary On This Subject. 8th ed. London: Printed by Kerwood and Cox, 1820.

Peterkin, Allan D. One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

Reynolds, Reginald. Beards: Their Social Standing, Religious Involvements, Decorative Possibilities, and Value in Offence and Defence Through the Ages. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

Selig Polyscope Company. 1907 Catalogue of The Selig Polyscope and Library of Selig Films. Chicago, IL: The Selig Polyscope Co., Inc. 1907.

Waits, Robert K. Before Gillette: The Quest for a Safe Razor : Inventors and Patents, 1762-1901. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Enterprises, Inc., 2009.