UChicagoGRAD recognizes Black History Month by highlighting the first African American graduate students! The stories of Edward Alexander Bouchet and Georgiana Rose Simpson as the first African-Americans to earn PhDs in the United States are inspiring and as we look at these two graduate students.

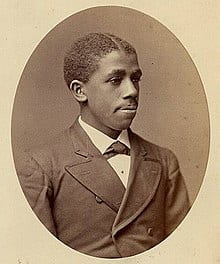

Edward Alexander Bouchet was the first African-American man to earn his Ph.D. from an American University, Yale College (what is now Yale University) in 1874. Throughout his education and career, he faced many challenges despite his intellect and success. While being highly talented and educated, he lived in a segregated society, in which not only his daily life, but his schooling affected his access to resources. His scientific research and professionalism were hindered by the types of labs he could have access to, resources provided by the school, and even support in the educational curriculum. Even post-graduation, his skills and education were looked down upon and he struggled to be employed in the field he earned his degree in.

Despite this, Edward Bouchet completed milestones in terms of graduate education for African Americans. Bouchet is recognized as one of the first 20 Americans (of any race) to receive a Ph.D. in physics. He stands as the 6th student from Yale to earn a Ph.D. in physics in its history and ranked 6th in his class at Yale out of 124 students. Bouchet was also elected to Phi Beta Kappa, being officially inducted in 1884, after a chapter reorganization. While this caused him to not be the first African American elected to it, the first being George Washington Henderson, he is recognized as one of the early few. His doctoral thesis centered on measuring the refractive indices of various glasses. Despite the academic excellence Bouchet exemplified, his post graduate career was almost unaffected. Unlike anyone else in the U.S. who earned a Ph.D. at that time, including Georgiana Rose Simpson, and for the next 80 years, Bouchet was unable to obtain a college (or university) position, because of his race. He accepted a position working at Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth, where he taught a variety of subjects other than physics. Philadelphia offered Bouchet access to the city’s considerable progress in education, which had been growing before his arrival. After the Civil War, the ICY played an important role in training the thousands of black teachers that were needed throughout the country to provide freedmen with the education they sought. Unfortunately, he continued to face hardship on the base of race, when many schools at that time were beginning to alter their course subjects. The Industrial Education models caused schools to steer towards vocational subjects, causing Bouchet to lose his job in 1902, when the all-white board members fired anyone who wouldn’t teach this model. Bouchet ended up as in itinerant teacher, working in many states, until he moved home due to health concerns. In his honor, Yale established both the Edward Alexander Bouchet Graduate Honor Society and the Bouchet Leadership Award, and the American Physical Society has named the original location of Yale’s Sloan Laboratory as a historic site to honor Bouchet.

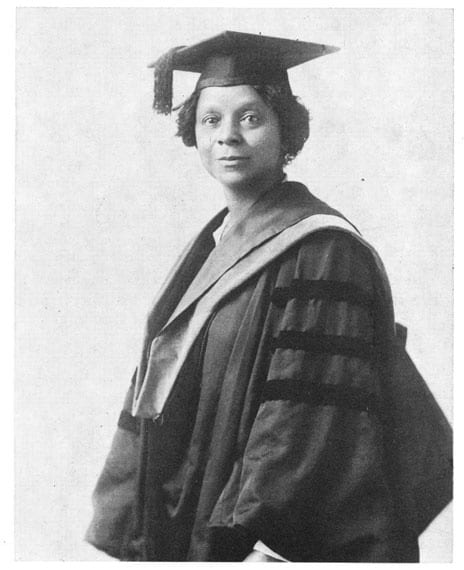

While Bouchet is a legacy for Yale, our very own University of Chicago has its own historic student in Georgiana Rose Simpson. She is recognized as the first African-American woman to receive a PhD in the United States, receiving her doctoral degree in German philology from UChicago in 1921. At this same time, there were two other scholars—Sadie Mossell Alexander (Ph.D. in economics) and Eva Dykes (Ph.D. in English philology)—who also earned their Ph.D.’s, becoming a striking trio of African American women earning their doctorates. Georgiana is recognized as the official first due to UChicago’ s early commencement. No doubt all these women faced substantial racism while trying to obtain their degrees, and Georgiana’s story is one that is retold every year as a reminder of the progress of graduate education for all at the University of Chicago. Georgiana arrived at UChicago in 1907 and was invited to live in the dorms on campus. Pervasive racism caused female students in her dorm to demand her removal. While initially this request was denied, the University of Chicago President at the time Harry Pratt Judson insisted that she move off campus, to which she did. Due to the extreme racial prejudice she faced against the predominantly white, southern student body, she finished her studies mainly through summer classes and correspondence courses. Her bachelors arrived in 1911, her master’s in 1920, and her Ph.D. in 1921. Simpson, along with her other black scholars, did not get university positions either, as most universities didn’t hire black women outside of the Home Economics courses.

Bouchet’s, Simpson’s, Mossel’s and Dykes’ race informed their life, but did not affect their scholarships. Bouchet and Simpson persisted in their ability to continue to teach and learn, despite the racism they faced. Bouchet spent his 26 years teaching physics, geography, astronomy, and a variety of subjects. Simpson was able to edit a biography of the Haitian independence hero Toussaint Louverture; African-American studies wasn’t officially accepted as a discipline at this time, and this opportunity was Georgiana’s work towards that field, despite her Ph.D. in German philology. The University of Chicago strives for equity for all students and continues to make improvements for its graduate students and achieving their academic success through offices like UChicagoGRAD.

Oh, more information? Of course we have it— Here are some resources to learn more about these figures, and about UChicago Diversity initiatives:

- Watch “Honoring Dr. Georgiana Simpson: First African-American woman to earn a PHD from UChicago” from the University of Chicago

- Read Yale’s Article: Honoring Edward Bouchet and the original Sloane Laboratory, where he studied | YaleNews

- Check out UChicagoGRAD’s Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives here.

- Diversity Advisory Board

- Check out the College’s Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives here.

- Reach out to Graduate Council’s Diversity and Inclusion Chair

- Featured Groups