Because the Old English poems Genesis A & B do more than just regurgitate they key aspects of their source material, telling the stories from the book of Genesis in a way that bears little formal resemblance to any Bible, we ought not to think of them as mere translations, but rather as poems in their own right, with their own agenda, and their own stories to tell. In one pertinent example, Genesis A & B include the story of Lucifer’s rebellion against God and subsequent fall (ll. 1-91; 235-337), a bit of prelapsarian history that isn’t found in the Vulgate, or at least not in Genesis. These sections of the poem tell of the heavenly war between the forces of God and the devil that ultimately casts Satan and his legions down into Hell. With that defeat in mind, I want to turn to the following excerpt:

Angan hine þa gyrwan godes andsaca,

fus on frætwum, — hæfde fæcne hyge —

hæleðhelm on heafod asette and þone full hearde geband,

spenn mid spangum; wiste him spræca fela,

wora worda. (ll. 442-46a)[Then the forsaker of God began to prepare himself, hastening in his armor–he had a wicked heart–he set the helm of invisibility upon his head and bound it tightly, fastened with clasps; he knew many speeches of crooked words.]

In this passage, just before he sets off to deceive Adam and Eve, Satan is shown girding himself in armor, as if for battle. To further bolster this reading, we can look more closely at the phrase “fus on frætwum.” Frætwum can have several meanings, encompassing not just “armor,” but more generally “ornament,” “decoration,” or “treasure.” These alternate definitions complement gyrwan, “to prepare, put on, make ready, adorn,” (a cousin of the ModE “gear”), indicating pretty clearly that even if it isn’t armor–though it probably is–Satan is putting something on. The crux of this short passage, I believe, is fus, which can be translated as “eager,” “prompt,” or “hastening,” but also “dying” and “death-ready.” Fus‘ denotative complexity recalls the the warrior ready for battle, resolute in his convictions, suggesting at once both preparedness and bravery.

Satan’s coming battle is not of a physical nature, as it was before. He dons the hæleðhelm, literally a “warrior-” or “hero-helm,” which appears to grant invisibility (the power of deception or deceit, per other translations), but he does not arm himself. At the end of this passage, the author remarks only that he knew a great many speeches of crooked or twisted words. Thus the battle in question is an internal one, a battle of hearts, spirits, or minds (concepts that are conveniently difficult to separate in this historical period). Furthermore, Satan’s armor of deception and (implied) waging of an intangible war anticipates, maybe unintentionally, the armor of God laid out in Ephesians 6.

Although this excerpt cannot hope to compare to the interpretive weight of the poem as a whole, we are no less justified in looking closely at what, if any, points it is making, or at how it fits into the larger Christian theology.

Anlezark, Daniel. 2011. Old Testament Narratives. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

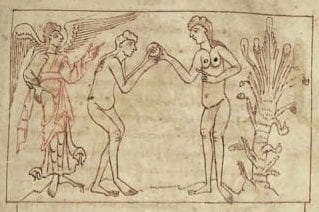

Image: Temptation and Fall of Adam and Eve – Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Junius 11 p. 31