Memorials are one of the most useful sources for historians of late imperial China like myself. In this case, ‘memorial’ refers not to a physical object like a monument nor to the word’s usual association with memory, like the upcoming holiday, except in a very abstract way. Instead, I’m talking about a type of document written by an official for the benefit of the emperor to inform him about local conditions, describe current policies and their effects, request a certain course of action, etc. – so like a memorandum/memo. Memorials, at least in theory, kept the emperor in touch with what was going on across the empire and in the capital. To the extent that they are preserved and are reliable, they are valuable sources for historians.

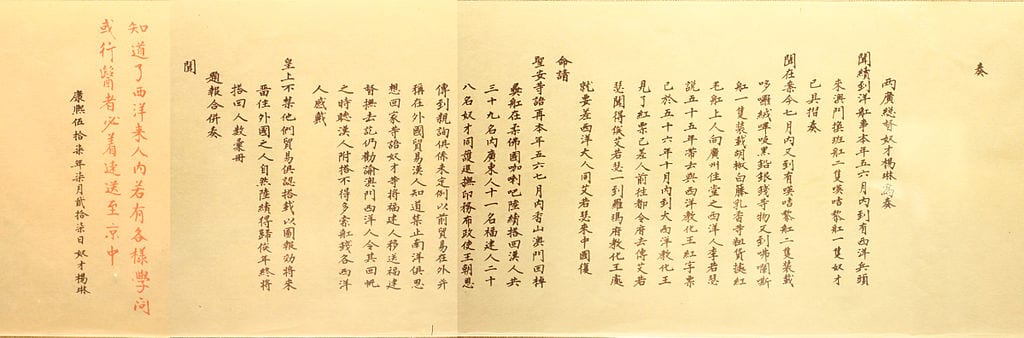

An example of a memorial bearing the emperor’s comments in red ink. The text is read top-down, right-left. The characters elevated above the rest of the text show respect for the emperor.

I’ve been spending quite a bit of time with memorials for a chapter I’m currently drafting on how warfare in the 1850’s and 1860’s, including between the Qing Dynasty and the Taiping (usually referred to as a rebellion but really so much more), affected Jinan. This chapter is partly a military history, exploring how Jinan fit into the overall strategic situation. Naturally, then, memorials containing reports from officials leading armies and organizing local militias are useful sources of information. Some of the memorials I’m using come directly from my research at the First Historical Archives in Beijing last year and in 2014. There are also a large number of relevant memorials reprinted in collections like the 26-volume Archival Materials on the Qing Government’s Suppression of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom 清政府镇压太平天国档案史料. Reprintings like this have the benefit of having printed text and being punctuated, which makes reading go a little faster.

As you might expect from a bureaucratic document, Qing memorials are formulaic and often mundane. A universal feature is the use of a series of words and phrases that memorializing officials used to convey their subordinate position (e.g. “I memorialize kneeling”) and the elevated status of the emperor (e.g. “Imploring Your sagely reflection”). They often set the context by quoting from another government document, either a report from a subordinate or an order from a superior. This allows us to reconstruct a kind of bureaucratic conversation. Memorials represented the voices of officials. The emperor spoke through a couple different channels. One was adding notations – in vermilion ink – directly on memorials, usually at the end but sometimes in the margins of the text. Another was through issuing edicts. Sorting through a series of memorials and edicts can sometimes magnify the tedium induced by the individual documents, especially when they keep quoting each other or when the emperor is relatively disinterested in the contents of a given memorial, giving it only the perfunctory notation of “Noted” (知道了). But sometimes, a dynamic back-and-forth among various officials, the throne, and past events gives these documents a life of their own.

One example is a memorial written by the Governor of Shandong, Zhang Liangji, on December 24, 1853. Two days earlier, Zhang had received a harshly worded edict, criticizing a course of action he had described in a previous memorial. In this new memorial, Zhang submitted himself to the emperor’s rebuke while trying to explain himself.

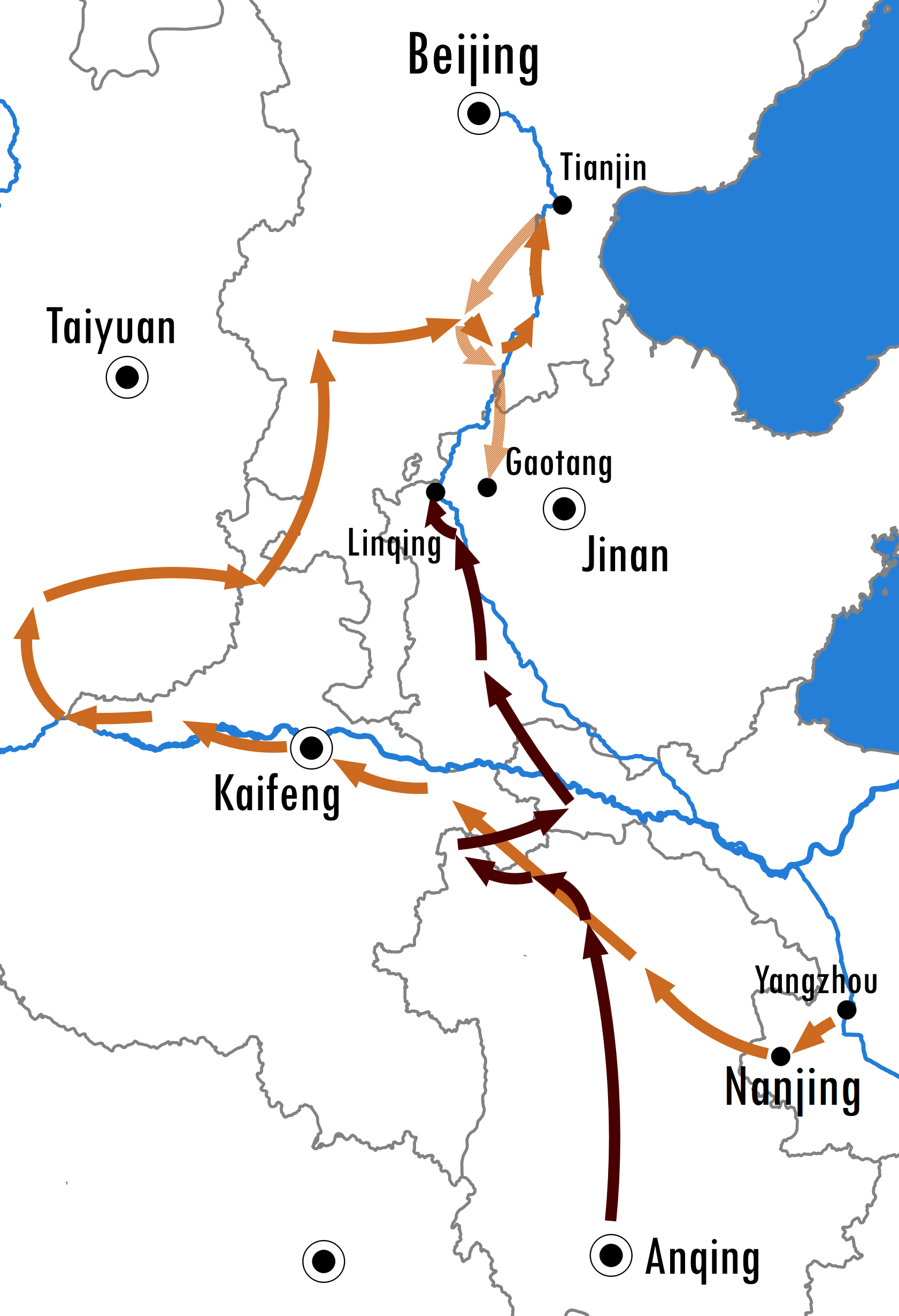

Zhang was facing a difficult situation. Earlier that year, Taiping forces had captured a series of important cities in Jiangsu Province, to the south of Shandong, and then dispatched an army northward to attack Beijing. Zhang’s predecessor, Li Hui, had effectively prepared defenses along the Yellow River, which divided Shandong from the provinces to the south. This forced the Taiping army westward, until they eventually crossed into Henan Province and continued northeast toward Beijing, looping all the way around Shandong. Qing forces scrambled to keep them from advancing northward and to keep them from heading back south into northern Shandong. At the same time, though, Zhang was worried about the possibility of another Taiping army attacking from the south. Somehow, he needed to simultaneously oversee armies in northern Shandong – arranged to defend against the first Taiping army – and defenses in southern Shandong.

The orange arrows show the path of the first Taiping army, around Shandong Province. Zhang was right to worry about a second invasion. The red arrows show the path of a Taiping army that crossed the Yellow River directly into Shandong in 1854. (GIS data from CHGIS.)

Since Jinan – the provincial capital – was in the center of the province, he decided he might as well station himself there. That left subordinates in charge of affairs in both the north and south, but put him in position to keep an eye on both fronts, see to the defense of Jinan itself, which was naturally of some importance, and handle other affairs he had been forced to delegate while absent from the capital. This seemed like a good plan.

The emperor disagreed. In an edict he castigated Zhang for staying behind in Jinan while his subordinates took charge of the armies in the northern part of the province that were supporting the fight against the Taiping. He told Zhang to go to the place where he was most needed, which was certainly not Jinan since it was by no means under direct threat.

So, Zhang wrote this memorial to back-track. He explained that he was on his way to inspect the encampments in northern Shandong and would continue to assess where he was most needed. He tried, though, to sneak in a bit of self-justification, emphasizing the importance of Jinan, which was, after all, the provincial capital.

The emperor did not take kindly to this. Interjecting in the margins of the memorial, he commented, “In Shandong, of course [Jinan] is of fundamental importance. But compared to the overall situation in the northern provinces and the importance of the capital, it is another story.” The emperor went on to review Zhang’s past performance fighting against the Taiping, which had been less than exemplary. While he was governor of Hunan, the Taiping had managed to capture the capital, Changsha while he was elsewhere with his troops. The court reminded him that he hadn’t always prioritized defending provincial capitals, but rather seemed to prefer being wherever the rebels were not:

When there were rebels at Changsha, you kept a distance from them [and stayed] at Changde. Duliu [north of Shandong] has rebels, and you have left the provincial commissioners at the front line while you have withdrawn to the rear, again keeping them at a distance. If you say that the provincial capital is fundamental, then what about this: was Changsha not fundamental to Hunan? We are not excessive in this criticism; it is all in order to punish your mind that we send this.

The emperor kept up his caustic exhortation in the rescript he attached to the end of Zhang’s memorial, writing, “You are not untalented and not incapable of pulling yourself together. If only you will rouse yourself a bit, then naturally there will be a day when you show it. Make an effort! Make an effort!”

Such emotive and immediate responses to memorials are more the exceptions than the rule, which is why this memorial in particular stood out to me. It is a good example, though, of how interesting memorials can be but how also how important it is to read them in context. Zhang’s memorial only makes sense if we read it in light of his previous reports and the throne’s responses. Moreover, the seemingly minor issue at stake – where Zhang positioned himself – is relevant only in light of the geography of the military campaigns taking place in Shandong and other provinces in North China. Zhang’s personal history – helpfully highlighted by the emperor – provides further context for understanding this back-and-forth.

Since not all memorials are so direct, it can take reading quite a few to pick up a story. But the possibilities – usually hiding beneath the surface, but sometimes right in front of you – are what make these such a useful but frustrating source.

If you enjoy reading about the sources I’m using in my research, check out my posts about local gazetteers and a document that sums up what my dissertation is about.