Paul Scheerbart, Gallery of the Beyond

Gallery of the Beyond (1907)

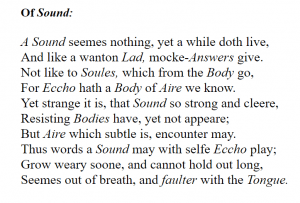

Written and Illustrated by Paul Scheerbart

For my presentation, I would like to introduce the short text “Gallery of the Beyond” by the German fantasist Paul Scheerbart. This brief portfolio consists of a written text and ten lithographs, also illustrated by Scheerbart, published in 1907. The text is in the form of a newspaper article or press release, hailing the discovery of new photographs from “beyond the orbit of Neptune.” According to the narrator of this piece, “microscopic study of the photographic plates provided by the great astronomical observatories” have turned up “cosmic images” depicting “new views of our world that are nothing less than exhilarating” (p. 283)

The accompanying artworks are meant to represent the cosmic beings and alien life-forms recorded in the interstellar space beyond Neptune, paradoxically described as gigantic in size despite the microscopic medium on which they were captured. Rendered in pointillism as whimsical grotesques, the images are suggestive of imps, angels, folkloric creatures, and pareidolic forms in dust and water. In lucid yet fantastical prose, Scheerbart describes “planets on whom we can discern a plethora of massive external limbs,” as well as comets that are “component beings that have detached themselves from the creatures beyond Neptune.” In Scheerbart’s narration, the astral transmutes into the biomorphic: “We must therefore assume that the round planets too are thoroughly independent, sentient living creatures… the great beings beyond Neptune prove to us that our solar system consists of ‘living beings.’ “ (p. 283-284)

Importantly, Scheerbart insists upon an ethical dimension to humanity’s encounter with these new images of extraterrestrial life: “We must now refrain from any further attempts to meet the newly discovered creatures beyond Neptune with further attempts at explanation; we must first seek slowly to familiarize ourselves with them. The magnificent and marvelous life in our solar system that is just now becoming visible to our eyes, is so vast that for now, a long admiring silence seems the best course.” (p. 284) Pace Levinas, the patient and humble contemplation of the newly revealed life forms must renounce the claims to familiarity and recognizability embodied by the human face. Scheerbart writes that “most of the cosmic beings […] possess no such face” and that they therefore “ought not to be judged from a purely aesthetic standpoint, as such aesthetic judgments can only proceed from our habituation to the appearance of earthly beings.” (Ibid.) This, then, is an ethics of alterity that is resolutely post-human, even as it inscribes the scene of ethical relation upon the human encounter with the cosmos.

Scheerbart’s text is also eminently political, touching obliquely upon the volatile contradictions of otherness, technology, and spatial perception that were to incinerate Europe only seven years later. Reflecting upon the First World War in 1928, Walter Benjamin interprets that epochal catastrophe as an abortive attempt to recapture the cosmic experience once accessible to ancient humanity. Benjamin outlines the atmospheric dimensions of World War I: “the last war […] was an attempt at new and unprecedented commingling with cosmic powers. Human multitudes, gases, electrical forces were hurled into the open country, high frequency currents coursed through the landscape, new constellations arose in the sky, aerial space and ocean depths thundered with propellers, and everywhere sacrificial shafts were dug in Mother Earth.” For Benjamin, this “wooing of the cosmos” could only end in tragedy, distorted as it was by the ruling class “lust for profit” and fantasies of mastery over nature (pp.103-104.)

By contrast, “Gallery of the Beyond” presents a vision of relating to the aerial space that is not rooted in rapine or the will to assert possession. Scheerbart’s contemplation of our celestial surround is routed in passionate respect for all living beings, including the cosmos whose liveliness has only recently been revealed. As in his iconic writings on the utopian potentiality of glass architecture, Scheerbart sees aesthetic experience as a site for overcoming violence— starting with the human, perhaps, but moving onwards to greater, more expansive planes of existence to encompass the created universe. As he writes in his “Mottoes for the Glass House,” “Colored glass/ destroys all hatred at last” (p. 135.) In this text, it is the clear glass of the photographic plate that turns before us the image of the Other, for whose sake we are tasked with overcoming hate.

In a late essay on Scheerbart, Benjamin quotes the fantasist thus: “Let me protest against the expression ‘world war.’ I am sure that no heavenly body, however near, will involve itself in the affair in which we are embroiled. Everything leads me to believe that deep peace still reigns in interstellar space” (p. 386.) Unfortunately, as we know, Scheerbart’s utopian fictions were not enough to prevent the violent conflagration that ensued. He died in 1915, just one year after war broke out— most likely from a bout of alcoholism induced by wartime stress, although it is rumoured that he starved himself to death in protest (see Indiana pp. 155-156, Turner p.16.) His cosmic visions remind us of the possibility of another history, of the history of a 20th century that never emerged but perhaps still could: one in which the borders between nations and cosmic states would be abolished; one in which, to quote Benjamin a final time “technology, by liberating human beings, would fraternally liberate the whole of creation.” (Ibid. p. 387.)

Works Cited:

Benjamin, Walter. One Way Street and Other Writings. Trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter. London, UK: NLB, 1979. Print.

_____________. “On Scheerbart.” Selected Writings Vol. IV 1938-1940, ed. Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 2006. Print, pp. 386-388.

Indiana, Gary. “A Strange Bird: Paul Scheerbart, or The Eccentricities of a Nightingale.” in Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader. Eds. Christine Burgin and Josiah McElheny. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2014. Print, pp. 155-160.

Scheerbart, Paul. “Gallery of the Beyond, 1907” in Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader. Eds. Christine Burgin and Josiah McElheny. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2014. Print, pp. 280-295.

_____________. “Glass House Letters, 1920” in Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader. Eds. Christine Burgin and Josiah McElheny. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2014. Print, pp. 130-143.

Turner, Christopher. “The Crystal Vision of Paul Scheerbart: A Brief Biography” in Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!!: A Paul Scheerbart Reader. Eds. Christine Burgin and Josiah McElheny. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 2014. Print, pp. 11-20.

1 Comment Already

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Apologies for my crappy “image scans” !!