Margaret Cavendish’s Vital Echoes

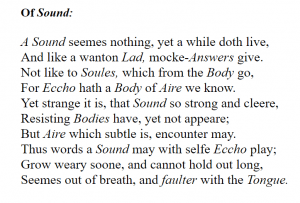

For my short presentation today, I want to add to our “Breathworks” a poem from Margaret Cavendish’s 1653 assemblage of Poems and Fancies, titled “Of Sound and Eccho” (1664 title):

Margaret Cavendish was a 17th century philosopher, poet, proto-science-fiction writer, and playwright whose materialist philosophy largely responded to Cartesian dualism, as well as the dualism of Henry More, with a truly original, more complex and various understanding of matter, minds, and Nature as a whole. Her tripartite organization of the always intermixed degrees of matter—the rational, sensitive, and inanimate parts—radically resisted the often-misogynistic mind-body dichotomy that associates the feminine with the body (material and disorderly) and the masculine with the mind (subtle and orderly). Her more “fanciful” work (as she calls it), her poetry, fiction, and plays, were generally dismissed by her contemporaries as contradictory, idiosyncratic, and vain—some going as far as invoking madness to explain her published works (Hock, 767; Stevenson, 528). For Cavendish, however, these works of “fancy,” as well as her philosophical texts, are still “effects [or] actions of the rational parts of matter,” and as such serve as a playful laboratory of intellectual experimentation (“To the Reader” section for The Blazing World). More recently, critics have finally come to appreciate her “postmodern” embrace of contradictions, “randomness,” and the frequent foregrounding of an, at once, self-enclosed and relational perspectivism in both her philosophy and more deliberately aesthetic work (Scott-Baumann, 60; Stevenson, 527). But these fanciful works often (and especially with “Of Sound and Eccho”) do more than employ a kind of Lucretian use of verse, one understood as a sweet honey to help make the bitter truths of philosophy go down. In “Of Sound and Eccho,” we see Cavendish instrumentalizing an exploratory poetics that latches on to the elusive causal and material interrelations of sound, air, and breath to work through a conception of each that develops, as opposed to simply conforms to, her theory of vital materialism.

The poem starts off and remains surprisingly speculative compared to some of Cavendish’s other poems, which tend to at least end up simply versifying her philosophical assertions. Here, however, there is a persistent “seeming” of nothingness or ephemerality, in the first and last lines that speaks to an ongoing exploration of the phenomenology of sound as it intersects with Cavendish’s materialism. The indefinite transience of “A Sound” that only “a while doth live,” perhaps, at first seems counter to the perpetual motion and existence of material bodies that constitutes her system of nature. “A Sound” was changed to “Eccho” in 1664, which I think illustrates a developing focus on the echo as a way of understanding the vitality of sound, suggesting maybe that every sound is always already an echo. Edits like these, prevalent in the later editions of this collection, reflect the processual nature of Cavendish’s experimental poetry—she does ultimately conform to traditional meter and rhyme, but her attention to the materiality of language in the editing process (Scott-Baumann, 61) is reflected, I think, in her meditations on the lingering materiality of sound. She asserts in her later philosophical texts that matter cannot be created or destroyed, nor can traits like sound or color be said to exist abstracted from the material bodies they qualify, so what exactly should one make of this transitory phenomenon?

In her most eminent philosophical text, Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy published thirteen years later, Cavendish rejects the idea that sound only exists in the sensitive organs of the sentient animal (173). Rather, the acoustic emissions of one’s voice, or from the collision of two material bodies, take their form in correspondence with the particular self-knowledges and agency of all the bodies involved and, thus, would materially exist regardless of a sentient listener since all matter has its own form of “listening,” or perception (174). The way echoes illuminate this ubiquitous material self-motion is what Cavendish is working toward here in this piece. The line “For Eccho hath a Body of Aire we know” deploys the indefinite article, again, to reassert the particularity of every instance of echo and also affirm a quasi-anthropomorphic agency of the very space in which the sound reverberates (keeping in mind that “space” for Cavendish is still completely filled with material bodies, albeit very “subtle” ones). The rhyming of “cleere” and “appeare,” referring to the clashing clarity and ephemeriality of sound, reflects an effort to expand perceptive understanding beyond the immediacy of the visual, and beyond animal bodies altogether, to consider the variety of perceptions in every single particle of matter. The way echoes can uniquely “encounter” air demonstrates for Cavendish the omnidirectional causal relationality of all matter, while reaffirming the material agency of sound when interacting with other bodies of air, occasioning the voluntary, if brief, patterning out of sound configurations.

In another poem titled “What Makes Eccho,” Cavendish writes, “As Sugar in the Mouth doth melt, and taste, / So Eccho in the Aire it selfe doth waste.” This enhances the meditation on the acoustic element of the semantic in the final lines here—how there’s a kind of playful reflection in echoes, if only until they seem “out of breath, and faulter with the Tongue.” Taken together, these lines convey a momentary sweetness in the disintegration of sound into aerial matter, which is compared to the disintegration of particles in the mouth. Here, the Lucretian sweetness of language and verse is more than a container for philosophy, but also a process by which Cavendish materializes her philosophy, a pleasant but still rigorous process. In these last lines, air and space become receptive bodies that are fundamentally changed, perhaps nourished or polluted even, by sound—how might we understand sound pollution through Cavendish’s vital echoes, through an understanding of sound as the air itself perpetually inhaling and exhaling the industrial hum? The fatigue/weariness/shortness of breath that Cavendish uses as a metaphor for the brevity of the echo asks us to extend the necessary connection between breath and voice into a respiratory milieu that speaks back to us as much as we do to it—and perhaps in the same way Cavendish speaks back to herself when editing later editions. I believe Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies is part of laying the foundation not just for the naturalism in contemporary science and philosophy, but also for presencing, as Lyn Hejinian insists we do, the material reverberations of history, the vital echoes in every work of art as well as space. “Echoes,” Hejinian writes “aren’t inherently empty” (which also serves as a refrain in Jordan Scott’s meditations on ambience in Guantanamo); they acoustically pulsate in time with the lives, and lungs, of the infinitely various parts of matter.

Works Cited

Cavendish, Margaret. “Of Sound,” Poems, and fancies written by the Right Honourable, the Lady Margaret Newcastle, London: Printed by T.R. for J. Martin, and J. Allestrye, 1653, Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A04486.0001.001.

Cavendish, Margaret. “To the Reader,” The Blazing World and Other Writings, Penguin Classics, 1994, 123-24.

Cavendish, Margaret. “What Makes Eccho,” Poems, and fancies written by the Right Honourable, the Lady Margaret Newcastle, London: Printed by T.R. for J. Martin, and J. Allestrye, 1653, Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A04486.0001.001.

Hejinian, Lyn. “Lyn Hejinian: Turbulent Thinking,” Jacket 2, 8 April 2015, https://jacket2.org/commentary/lyn-hejinian-turbulent-thinking.

Hock, Jessie. “Fanciful Poetics and Skeptical Epistemology in Margaret Cavendish’s Poems and Fancies.” Studies in Philology 115, no. 4 (2018): 766-802. Accessed November 25, 2020. doi:10.2307/90025019.

Scott-Baumann, Elizabeth. “Margaret Cavendish as Editor and Revisor,” Forms of Engagement: Women, Poetry and Culture 1640-1680. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Stevenson, Jay. “The Mechanist-Vitalist Soul of Margaret Cavendish.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 36, no. 3 (1996): 527-43. Accessed November 24, 2020. doi:10.2307/450797.

SFU Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences. “Jordan Scott, SFU Writer in Residence on Guantanamo Bay Detention Center,” 1:32:04, 29 August 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MK_XRcA28_E&t=4214s.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.