By Rob Mitchum // February 5, 2015

When the metagenomics platform MG-RAST was launched in 2007, data was scarce. Created as a public resource for annotating microbial genomes from environmental samples, MG-RAST originally served a small community of scientists with relatively small datasets, due to the great expense of gene sequencing. But as that cost plummeted and metagenomics research boomed, the platform swelled to its current size of over 66 trillion base pairs of data — a rich sea of information on the microbial world, but one that presents challenges for scientists who seek to find and export the data they need.

In response to increased demand for normalized data from MG-RAST, the team behind the platform recently unveiled a new route of access: an application program interface, or API. Today a common feature of data-heavy websites, APIs work as a kind of library checkout desk for websites, allowing users to acquire the data they want in a standardized format under terms that the website owners are comfortable with. With MG-RAST’s shiny new API, researchers can now get the computed data they need for further bioinformatics work, with a minimum of hardware and software investment on their own end.

“The problem was, if anybody wanted to start the business we are in, the assumption in biology was that you would have to start from scratch — in order to test, you needed to build the entire system,” said CI Senior Fellow Folker Meyer, one of the creators of MG-RAST. “The API exposes the data and all computational side products, and enables lots of people to make different uses of the data in the future.”

For many researchers, the API will help fill important gaps in their “data pipelines” — the path from sequencing through annotation (the identification of particular proteins or functions within the gene sequence) to further analysis and experiments. While MG-RAST has been used to annotate over 160,000 metagenomic datasets already, the graphic user interface created limitations preventing researchers from extracting certain types of data or metadata, or creating an automatic script that uploads raw data and downloads results without human intervention.

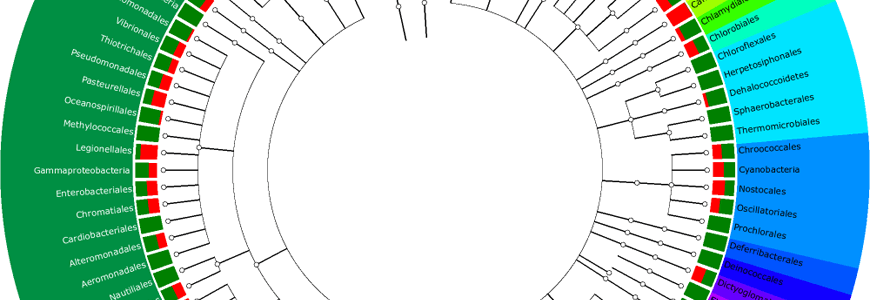

Using different API call methods, users can pull out data by functional or taxonomical categories — for example, all reads marked as proteases from marine metagenomes (one of several demonstrations provided in a recent PLOS Computational Biology paper) — or search within specific projects or samples. The ability to “filter” data in this way eases some of the growing data transfer obstacles in bioinformatics, the authors write, as analysis can multiply the “data footprint” of a given sample 10 times over.

The MG-RAST team already has witnessed the popularity of the new API, with over 100 researchers using it in the months since the launch. Internally, the Argonne-based team is also using the API to feed another biology platform: KBase, a predictive modeling platform for microbial and plant communities, which will extract MG-RAST data for use in its analyses.

During the humble beginnings of MG-RAST, Meyer and colleagues never considered that an API would be necessary, he said. But the platform’s overnight success and sustained use motivated the belated addition in order to help feed the next generation of metagenomics applications.

“MG-RAST happened by accident,” Meyer said. “We built it near the beach in San Diego, used it, and left it open for friends who knew about it. When we came back after two months, it had hundreds of users and lots of datasets, and it’s kept mushrooming from there, gaining features. So an API was a late consideration.”

The addition reflects broader trends in biology as it becomes a more data-intensive field, Meyer added.

“Biology is going through a dramatic change, as it used to be extremely data poor,” Meyer said. “Biology has had to totally redefine its computer science infrastructure, because DNA sequencing became 10,000 times faster and cheaper. In five years, we went from getting a little bit of data to drinking from the firehose.”