In the backwoods of Virginia, past a crackling gravel road and a sea of golden rods, three tents sit sixty feet in the air. It is hard to see them at first. A few hundred yards down the road and the tents are completely blocked by lush green branches. But if you keep driving down that gravel one-way – past the 20-something year old standing with a walkie talkie, past the banner that swings over the road reading “DOOM 2 THE PIPELINE,” the tents come clearly into view. The tents rest on sheets of plywood that are strung to tree branches. Ropes dangle from the platforms. If you stand directly beneath the tents and look up, you can see a message painted on the bottom of the plywood that reads: “EXPECT RESISTANCE.”

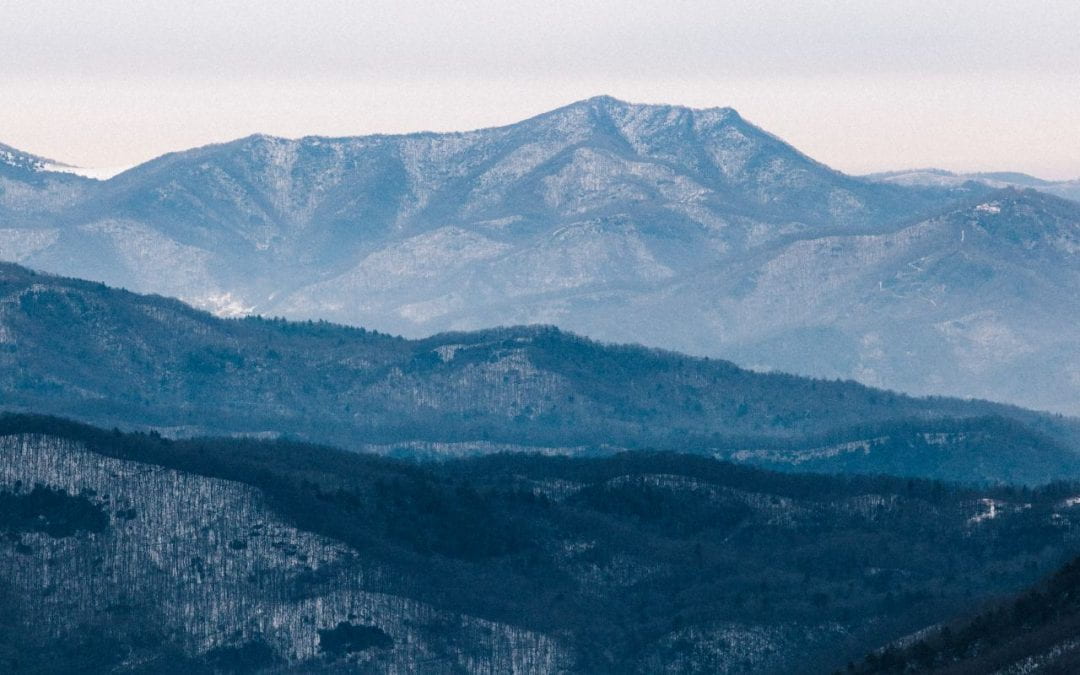

The trees that hold the tents are stationed on the side of a mountain, leaning at what seems like an impossible angle. It’s hard to imagine the people who live there get much sleep. A short walk away from the tents is a makeshift camp: a grill, a firewood-chopping station, a cluster of lawn chairs where a few people sit talking. The people speak quietly, casting distrustful glances over their shoulders. A river cuts through the camp, giggling and spitting. On this side of the road, the land bursts with trees; it is a vision of green interrupted only by the expanding autumn shades.

The other side of the road is clear cut. The ground there is a tired bronze, sagging into a sheet of tarp used to hold back the erosion.

Jammie Hale stands in the road between these starkly different landscapes. Hale boasts a truly enormous walrus mustache and wears a US army cap, jeans, a jean jacket, and cowboy boots. He leans on a wooden cane that has a carved black snake twisting around it. He whittled that cane himself. He’s 48 years old. And he’s pissed off.

“Three years ago, I was raising animals, building a farm, I had a family,” he says. “Now I have none of that. It’s just me now. All the animals are gone.

Everything’s destroyed. The pipeline has destroyed my life.”

The Mountain Valley Pipeline is an unfinished 303-foot long natural gas project that, if completed, will run from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia to central North Carolina. As an interstate pipeline, the Mountain Valley Pipeline is regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The pipeline was approved for construction in October of 2017 and was expected to finish construction in October of 2020. As of now, Mountain Valley Pipeline, LLC claims that the pipeline is 92 percent constructed; however, opponents argue that this statistic is misleading and Allegheny BlueRidge Alliance used data from construction reports to show that the pipeline is actually just over 51 percent complete and only 15 percent in Virginia.

Since its approval, the pipeline has raked in over 300 water violations and $2 million in fines in Virginia alone. The project has faced delays in construction so extreme that the company was forced to file for a deadline extension in August of 2020. The project’s costs have swollen from $3.5 to $5.5 billion. And, of course, the company has faced Appalachians Against Pipelines, a group of environmental protestors who sit in the trees that the Mountain Valley Pipeline workers are supposed to cut down.

“They’re opposing energy. They’re opposing national security,” says Charlie Burd, the executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of West Virginia. “These pipelines are extremely important. We’re going to produce a resource that our country needs.”

Jammie Hale was born and raised in Giles County, Virginia, about an hour out from the protest site. His family has lived there for generations. Hale lives by an old gravel road where people drink, ride ATVs, and hunt. Over the years, he has had plenty of issues with bear hunters and deer poachers. But he had never dealt with pipeline workers before. Hale has rich neighbors who inherited an old plantation and live in Connecticut most of the time, only visiting Virginia about once a year to check in. While the neighbors were gone, Hale tended to their land. He mowed, monitored for trespassers, and generally took care of the place. In exchange, he was given free range of the property. He could hunt, pick berries, cut firewood, ride his ATV. But one morning, he spotted fourteen trucks at the bottom of his neighbor’s driveway.

Hale went up into the woods and found fourteen people carrying surveying equipment. He asked them what they were doing. “You’re clearly trespassing here,” he said.

The strangers explained that they were surveying the land for a pipeline that could possibly cross through the area. Hale told them that unless they could provide written permission from the commonwealth of Virginia then they had to leave. After they took off, he called his neighbors. Yeah, they’d heard about the pipeline. Until Hale heard otherwise from them, he should treat the workers like trespassers.

Hale couldn’t stop thinking about it. He googled the pipeline. Spent all night researching it. Hours went by. Two in the morning: YouTube videos of elderly locals forced to leave the homes they lived forty years in. Three in the morning: Articles about a 61-year-old woman and her daughter, tree-sitting on their own family orchard in Bent Mountain. Five in the morning: Testimonies from a man who was forced off his land after his family lived there for eight generations. By six in the morning, Hale was sobbing.

“When I seen the hurt in these folks’ eyes, I had to get involved,” he says.

Hale’s involvement in the protest has taken many forms. He bakes bread and brings it to the tree sitters. He freezes ice to help protestors store food at the blockade. He paints banners, proudly pointing out which ones are his. He shows up at hearings when fellow protestors are arrested.

“If I have to go to jail to save these kids, I will,” he says. “If I have to go to jail to feed these kids, I will.”

One of those “kids” is a tree-sitter who uses the pseudonym Kermit. Every morning, Kermit wakes up among the branches, looks out from his tent, and sees the clear-cut mountain on the other side of the road. The smell of pine is sharp and cool. Mites and walking sticks crawl over his legs.

He stays in the tree from light to dark, blocking the path of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. A couple times a day, he’ll lower a bag tied to a rope, which protestors on the ground will fill with food for him to haul back up. Journalists often ask him how he uses the bathroom, and he always refuses to answer.

Kermit is a soft-spoken guy – a vegan, an environmental activist, and an introvert. He is more than happy to spend his days alone high in the branches. He gets better cell service in the tree than the people do on the ground. On a typical day, he will eat greasy potatoes and fruit, talk to ground support, clean any mess he has made on his plank, and read. Most recently he has read Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology by David Graeber.

He had a “chill” childhood and gets along with his parents. “Whatever anti-authoritarian stuff I have isn’t, you know, directed at them in some weird Freudian way,” he says. “They’re more scared of me fucking up my whole life by getting felonies.”

As a kid, Kermit loved the wilderness. As a teenager, he became involved with social movement organizing. He always loved to climb. Tree-sitting was the natural intersection of these interests. “I think a lot of glory goes to climbers and tree-sitters and stuff because it’s this specialized skill that everyone is sort of enthralled with,” he says. “All the glory goes to these people in these high-risk roles or whatever but the vast majority of movement work is, like, you know, making the greasy potatoes. Doing the care work to make it all happen. And so I think, you know, while I’m the one who gets to talk to you on the phone, those are the people who mostly make it happen.”

Truthfully, the risk is high for every direct-action protestor – whether on the ground or in a tree. Every day, Kermit and his ground supporters risk being put into handcuffs for standing in the way of the construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. The casual observer would be quick to question why anyone would risk their future to protest a pipeline – and Kermit would be quick with an answer.

“It might look like some grubby kid who stopped [pipeline] work for three hours,” he says. “But these things interlock and add up.”

Indeed, according to a 2018 release from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the “Keep It In the Ground Movement” – an umbrella term for widespread efforts to cease harvesting fossil fuels – has cost the fossil fuel industry $91.9 billion. By swelling the costs, many protestors hope to slow the construction of natural gas infrastructure and encourage a national transition to clean energy. But direct-action protests are about more than causing financial damage to energy companies. These protests are, at their center, about different fundamental ways of understanding humanity.

Keith Woodhouse is an associate professor of history at Northwestern University and author of The Eco-Centrists: A History of Radical Environmentalism. In the discussion of direct action motivation, he notes a key concept in his field of study: eco-centrism.

Eco-centrism is a philosophy that is based on the moral equivalence of human beings and the nonhuman world. In other words, humans are not morally situated above animals, or even above trees, rivers, and flowers. We are not more important than the non-human spaces we inhabit and draw energy from.

Eco-centrism is a minority view, to put it lightly. Throughout history, humans have long considered themselves the morally primary species and considered themselves separate from and positioned “above” the non-human world. The human-centric standard makes for a frustrating disconnect when eco-centrists try to protect the land they care about.

“The urgency that you bring to it is not necessarily going to be reflected in the conventional political process and standard means of reform,” Woodhouse says. “And so in order to act according to the urgency you feel, the beliefs that you feel, sometimes and maybe often it requires operating extra legally, or at least outside of the conventional political process. And that means engaging in direct action.”

Direct-action protestors are driven by a deep sense of urgency. They are reacting to what they perceive to be an existential threat – namely, the threat of climate change.

“If you believe that there is a crisis at hand – especially if you’re a young person, right, and you have the vast majority of your life to live – you feel a great urgency to do something about it,” Woodhouse says. “If you believe that the people who are supposed to be guiding policy are essentially ignoring what is one of the great existential crises of our time…you know, at that point, it sort of feels like it’s not clear what other options you have other than to engage in direct action.”

On the flip side of the issue, many pro-energy Americans perceive the environmental movement as an existential threat to their lives. The halting of the fossil fuel industry would undoubtedly come at the cost of many Americans’ economic livelihoods. Environmentalists would argue that a much greater threat to these communities is posed by the unsafe management of the fossil fuel industry and the approaching catastrophes of climate change, but that doesn’t do much to convince pipeline workers who are just trying to get through the day.

“It’s often easiest to look at the people who are immediately in front of you, right, with the signs and the banners, who are sitting in trees or locking themselves to trucks and say, ‘These are the people who are threatening us,’” Woodhouse says. “Especially if those people look in any way unfamiliar.”

Hale grabbed his bandanna – a red one, which was a reference to his father and other Virginian “red necks” who worked in the Virginia coal mines. He jumped in his truck, a 2004 Dodge Pickup. The early sun bled through his windshield. He drove to Peters Mountain and was greeted by a flood of blue lights. The Forest Service, state police, and Giles county police were all there. On the other side of the gate was a woman, fifty feet in the air, in a monopod.

A monopod is essentially a tall pole with a platform attached. A sign dangled from the monopod reading: “THE FIRE IS CATCHING. NO PIPELINES.” According to Hale, the monopod was rigged to the gate so that if anyone tried to open the gate, the monopod would swing to the ground and crush the woman inside it. The woman identifies herself as Nutty.

Appalachians Against Pipelines rallied behind Nutty. Law enforcement arrested anyone who set foot within 125 feet of the monopod, so the supporting protestors set up camp exactly 125 feet away. Between fifteen and twenty people lived on the camp daily, monitoring the monopod and law enforcement. Jammie Hale was among them. The camp was stationed on a steep incline, earning the camp its nickname “Slanty Camp.” In the days that followed, the National Forest Service cut Nutty off from food and water. Law enforcement arrested any supporters who attempted to bring Nutty supplies. The camp was placed under 24-hour surveillance.

“They brought semi-automatic weapons into our camp to arrest folks,” Hale says. “At nighttime, they would shine spotlights on us all night long, run a generator right beside our camp which made sleeping difficult. They were shining spotlights on the monopod from dark to daylight, trying to sleep deprive Nutty.”

Nutty stayed in the monopod for weeks. On the fifty-second day, she ran out of food. She collected rainwater on her tarp and held on for five more days. Her last night in the monopod, Nutty looked up at the sky. She wrote on Facebook: “I knew it was the last night I would spend here. I looked up at the stars and the moon, at the leaves lit by floodlights, looking for the right words but finding only the hardness in my throat and tears in my eyes at what they will do to this piece of road when I am gone, at all the countless struggles that end in mourning and in loss.”

In the end, Nutty spent 57 days on the monopod blocking the Mountain Valley Pipeline, LLC’s access to Peter’s Mountain in the Jefferson National Forest. Hale lived in the woods with the ground protestors for 52 of those days. Nutty left the site in an ambulance. Virginia State Police fingerprinted her while she lay in her hospital bed.

At her trial, Nutty was sentenced to 14 days in prison for blocking the road.

It was nasty stuff. Burn-your-eyes-out sort of scary. But when it happened, Hale’s mother and father showed up. Giles County is an impoverished rural community. No one had much. But they had each other.

His parents helped the farmer’s wife take care of her garden. They helped her can the food (“We didn’t go to the store and buy nothing. Hell, we didn’t know what grocery stores was,” Hale says), they helped her care for the cattle, and took the cattle to market for her. The rest of the community showed up, too. Everyone wanted to help.

“I seen community, and it stuck with me all these years, and it made me a better person,” Hale says. “But that’s where I come from. When people yell fire, we run with water. When we see people sick, we go get medicine.”

Today, Hale adjusts his army cap and leans back in his plastic lawn chair. His arms are gnarled with veins. “I’m being investigated as an eco terrorist,” he says.

In December of 2003, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General audited the FBI. The audit expressed concern for the FBI’s treatment of animal and environmental activists as terrorists. The audit further noted that the FBI’s weekly Intelligence Bulletins, which distribute criminal concerns for state and local law enforcement, focused not on “the high risk of radical Islamic fundamentalist terrorism but social protests or the criminal activities of environmental or animal activists.”

The audit pleaded that the FBI transfer the management of environmental and animal rights crimes away from the Counterterrorism Division and instead allow the Criminal Investigative Division to handle the issue. “We believe that the FBI’s priority mission to prevent high consequence terrorist acts would be enhanced if the Counterterrorism Division did not have to spend time and resources on lower-threat activities by social protestors or on crimes committed by environmental, animal rights, and other domestic radical groups or individuals,” the audit reads.

The FBI refused the request.

In November of 2006, Congress passed the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act. This legislation established that causing “economic damage to animal enterprises” through “loss of profits” or “increased costs” is an act of terrorism. The act also labeled the creation of “reasonable fear” of “vandalism, property damage, and criminal trespass” as terrorism.

During a 2006 Congressional Testimony on the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, eco-terrorism expert Will Potter said, “That clause, ‘a loss of profits’ would sweep in not only property crimes, but legal activity like protests, boycotts, investigations, media campaigning, and whistleblowing. It would also include campaigns of non-violent civil disobedience…Those aren’t acts of terrorism. They are effective activism. Businesses exist to make money, and if activists want to change a business practice, they must make that practice unprofitable.”

Since 2018, at least 18 states – including Virginia and West Virginia – have passed critical infrastructure laws. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines critical infrastructure as “the assets and networks that make up systems considered so vital that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on national security, economic security or public health and safety.” Privately funded pipelines are considered critical infrastructure. Critical infrastructure laws make it illegal to engage in “civil action” near pipeline sites. In West Virginia, just trespassing on land that contains critical infrastructure could result in the protestor paying a fine of at least $500 or going to jail between thirty days and a year. Vandalizing these sites or tampering with the equipment (locking yourself to an excavator, for instance) is a felony punishable by at least one year in prison. Not only that, but anyone who “conspires” with the protestors to trespass or vandalize these sites can also be charged with a felony.

These laws are troubling for people like Jammie Hale, who oppose the Mountain Valley Pipeline by supporting the direct-action protestors.

Although direct-action protestors receive most of the media attention, the battle against the Mountain Valley Pipeline has been a legal one, too. Legal groups argue that according to the Fifth Amendment, private property may only be taken when the project is for public benefit, and a private energy company’s financial interests do not align with public benefit. FERC promptly ruled that the pipeline is, in fact, for the benefit of the public – despite fabricated natural gas demand and most pipeline jobs being hired from out of state. Environmental groups filed a lawsuit against the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection after the department waived its authority to review the water quality impacts of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Appalachian Mountain Advocates represented a coalition of organizations in challenging a permit issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Many of these legal battles were met with delays – time during which the pipeline could continue construction. In October of 2019, the legal aspect enjoyed a partial win: following requests from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to examine the effect of the pipeline on endangered species, FERC issued a stop-work order.

“Fossil fuels have such immense power in our system,” says Joan Walker, the senior campaign representative for the Beyond Dirty Fuels Campaign. “So many subsidies and loopholes and regulations written for and by the industry. The fossil fuel industry over decades and decades has positioned themselves to have power to perpetuate their business model.” Walker maintains that it is essential to move, as a society, away from fossil fuel dependence. Charlie Burd, the executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of West Virginia, has a different perspective.

“There are probably few people in downtown metropolitan areas that want to look out their window and see a wind turbine,” he says. “Those will be located in places that have to inconvenience someone. Think about that. Those who protest fossil fuels – when you don’t use fossil fuels, you have to use wind and solar, and where do all the wind turbines and solar panels go?”

Although Burd presents a fair concern with the placement of wind turbines, it’s worth noting that pipelines have posed at least an equal inconvenience for those living in rural Appalachia. Living near a fracking sight means a plummeting home value, potential water pollution, and the risk of gas explosions. “We breathe the same air, we drink the same water, we raise our children in the same areas,” Burd says. “We want all these safe things for our children, and our families.”

Burd’s equivalence claim isn’t quite accurate either. Studies have consistently shown that pipeline projects such as the Mountain Valley Pipeline disproportionately affect lower-income groups, indigenous peoples, and black communities. The Clean Air Task Force and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People published a study that found that one in five African-American residents in West Virginia lives within a half-mile of an oil or gas facility. The study also found that nationally, African Americans are 75 percent more likely than Caucasians to live next to commercial facilities whose noise, odor, traffic, or emissions directly affect the population. According to a 2013 study by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, although 24.25 percent of all North Carolinians live within a mile of an EPA registered polluter, “41 percent of residents of Latino clusters and 44 percent of residents of African American clusters live within a mile of such pollution sources.”

The highest yearly salary Jammie Hale has ever received is $11,200 as a custodian for Virginia Tech. Crystal Mello is a 45-year-old cleaning lady who lives near Elliston, Virginia, ten minutes from the Mountain Valley Pipeline. In addition to her work cleaning houses, Crystal runs a jail solidarity group and works with the Hope Center. Despite grueling hours, she struggles to afford insurance and internet.

“I mean, we know this has happened forever, right?” she says. “It’s just now happening to white people. [The Mountain Valley Pipeline] is stealing people’s land for private gain, for all the wrong reasons. No one in this area is benefiting.”

Early this October, FERC lifted The Mountain Valley Pipeline’s stop-work order. FERC also granted the project an extended two-year deadline – and gave the greenlight for MVP Southgate, a 75-mile extension of the pipeline that would span from southern Virginia to central North Carolina.

The lifted stop-work order is grim news for Appalachians Against Pipelines. The tree sitters and their supporters have enjoyed relatively peaceful months during the stop-work order. Now, the daily threat of arrest looms over the camp.

“I just don’t never see life ever being normal again,” Hale says, standing at the protest site. In the three years he’s spent fighting the pipeline, Hale has lost his farm, his animals, and his family. He’s lost sixty pounds from stress. “And my story is just one story. This pipeline is 303 miles long.”

He takes his cap off, revealing a bald patch. Birds screech overhead.

“I’m trying to show people that we are dying,” he says. “That the earth is dying. Once I worry myself to death and I have a damn heart attack and they bury me, fine. They killed me. But what they don’t realize is I’m just a damn seed. Somebody’s gonna pop up, and they’re gonna take over where I left off.”

He shrugs, staring at the ground. Over his shoulder, the tents are visible in the trees. The tarp flutters in the autumn breeze.

A month later, the Montgomery County court filed an injunction against the tree-sitters. The tree-sitters were instructed to vacate the blockade within two days, after which the protestors would be fined $500 for each day they stay. Community members took to the streets to protest in solidarity with the tree-sitters. High school students touted posters reading “STOP WORK NOW” and “NO PIPELINE.” Ground supporters at the blockade were forced to tear down their camp and leave the premise.

Leaving the camp was in parts somber and hopeful as the community drew together to help. Some protestors worked in tears, others in silent rage. But regardless, they worked together. “A lot of people’s not used to working as a team. Everyone’s a lone wolf kind of deal,” says Hale over the phone. “But it’s come together and I think that’s what helps folks be able to swallow not being able to live there no more – the community around them. We’re here to support and to help out and do whatever needs to be done.”

The protestors stripped down the camp, both grieving the loss and marveling that the blockade has lasted for two whole years. When ground support departed, a remaining tree sitter named Acre wrote on Instagram that pipeline workers “spent the morning dismantling our fence using machetes and a chainsaw.”

According to Hale, many of the ground supporters have been living full time at the camp and now have nowhere to go. The protestors who remain in the trees have already gathered thousands of dollars in fines. “They’re already starting to rack up charges. But you can’t get blood from a turnip, you know?” Hale says. “When you try to impose sanctions against folks who don’t really have a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out of, like I said, you can’t get blood from a turnip.”

As Hale waits for the next step, he’s been plagued with anxiety and depression. To get through, he focuses on supporting his friends at all costs. “I’m heartbroken for them,” Hale says. “But I know my friends are strong. And if something happens and the Yellow Finch tree sitters do come down, there’s always other ways to slow this pipeline down. I have faith in my friends. I have great faith in my friends.”

Three protestors remain, huddled under sheets of tarp sixty feet in the air. The roar of excavators and the shouts of pipeline workers echo through the trees.

Kelsey Day Marlett

Contributor