Content Warning: Mentions of Self-Harm

National Suicide Prevention Hotline: 800-273-8255

For statistic graphics, please click the maroon-highlighted text below

Football is one of America’s favorite pastimes. A fun, physical sport that millions of fans across the country enjoy. The National Football League (NFL) brings in billions of dollars in revenue, with the Super Bowl having upwards of 92 million viewers in 2021. Though a seemingly carefree and fun sport, as researchers examine more injury data, evidence emerges of serious brain damage stemming from hard hits to players’ heads and resulting concussions. There has been a lot of controversy surrounding the NFL’s handling of the newfound research, from hiding certain information from players and fans to denying the negative effects of the sport altogether.

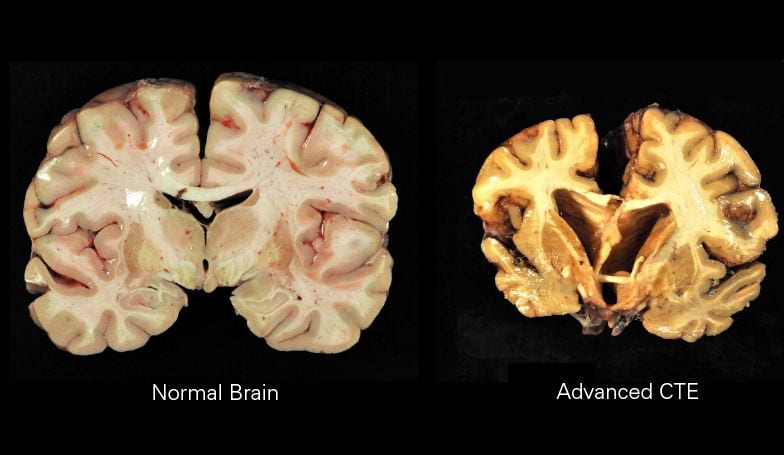

The main neurological condition that affects these players is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). CTE is a degenerative brain disease associated with repeated traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), including concussions and repeated blows to the head. Brains with CTE accumulate a protein called tau. The tau clumps together in the brain interrupting critical information flow. CTE takes 8-10 years to manifest, and the symptoms can vary from forgetfulness to violent tendencies and intentions. Unfortunately, CTE can only be diagnosed through autopsies, so it is unclear how many undiagnosed players suffer from the illness.

Despite this lack of clarity, out of 202 brains of former NFL players that were tested, 177 were diagnosed with CTE. An individual example that demonstrates football’s dangers on the human brain is the story of Aaron Hernandez. Hernandez was a tight end for the New England Patriots for 3 seasons and quickly become a star in the NFL, but his stardom was forgotten when he was arrested and charged with the murder of Odin Lloyd. After committing suicide in his cell, an autopsy revealed an incredibly severe case of CTE. The tragic story of Aaron Hernandez served as an eye-opener to football players and fans, emphasizing the need for more preventative measures and research on CTE.

Although there was clear evidence of the detrimental effects of trauma on the brain, the NFL didn’t acknowledge the issue until 2009 (Iskandar et al., 2018). As recently as seven years ago, one of the NFL’s top concussion specialists, Dr. Ira Casson, denied the correlation between football and brain damage, which incited public uproar that ultimately forced him to step down. Dr. Casson made troubling statements, including saying that there was no evidence supporting a connection between multiple head injuries and long-term neurological problems, concluding in his research study that the “majority” of players examined “had no clinical signs of brain damage.” The paper and study as a whole conducted by Dr. Casson has been completely disregarded and effectively viewed as inaccurate. In response, the NFL has disregarded his research, and in 2018, it reallocated more than $17 million in funding to concussion and brain injury research.

After the NFL’s support and acknowledgment of the brain injuries endured from football, the number of high school and collegiate football players has dropped dramatically. The NFL has made some positive changes to make the game safer. Players are immediately removed from the field when there’s a potential concussion, and if diagnosed, they can only return to play after completing a 5-step process including rest, exercise, and thorough examination from an independent neurological consultant. They have also banned helmet-to-helmet hits.

Despite the NFL’s strides in their understanding of the effects of football on the brain, there is still much more research to be done. Even with safer helmets, rules, and regulations, football is a sport that requires consistent human-to-human collisions. Football is always going to be a dangerous game, but hopefully, with time it can become a safer game that won’t have long-lasting implications on people’s brains.

Bibliography

Swetlitz, Ike, and Bob Tedeschi. “After a public fall, the face of NFL

concussion denial resurfaces.” Stat, 28 Apr. 2016, www.statnews.com/2016/04/

28/concussion-football-ira-casson-science/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2021.

Tharmaratnam, T., Iskandar, M. A., Tabobondung, T. C., Tobbia, I., Gopee-Ramanan, P., &

Tabobondung, T. A. (2018). Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Professional American

Football Players: Where Are We Now?. Frontiers in neurology, 9, 445.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00445

Maske, Mark. “NFL allocates more than $17 million to fund research into

concussions and brain health.” The Washington Post, 5 Jan. 2018,

www.washingtonpost.com/news/sports/wp/2018/01/05/

nfl-allocates-more-than-17-million-to-fund-research-into-concussions-and-brain-he

alth/. Accessed 7 Mar. 2021.

Resnick, Brian. “What a lifetime of playing football can do to the human brain.”

Vox, 1 Feb. 2020, www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/2/2/16956440/

super-bowl-2020-concussion-symptoms-cte-football-nfl-brain-damage-youth.

Accessed 7 Mar. 2021.