In this issue of the Forum, Scott C. Alexander offers a comparative historical analysis of two summers in American history of heightened anti-Catholicism (1854) and Islamophobia (2010). He characterizes these summers as “seasons of discontent” (cf. Shakespeare’s Richard III), although the “seasonal quality of social discontent has far less to do with the rhythms of the solar year, and far more to do with the nativist rhythms of our national psyche and mood.” As Professor Alexander writes, “This essay seeks to identify two specific ‘seasons’ of nativist U.S. American discontent with two minoritized religious out-groups: Roman Catholics and Muslims. It will argue that, as chronologically distant as these two micro-historical ‘seasons’ are from one another other (some 156 years), they share a striking number of common elements, not the least of which is the way in which they intersect with and reflect the macro-historical systemic perpetuation of white power and privilege as a key component of national identity. ” In the final portion of the essay, Professor Alexander considers the implications of his comparative analysis for thinking about the recently concluded presidential election season and the opening months of the 45th president’s term.

Over the next two weeks, scholars will offer responses to Professor Alexander’s essay. We invite you to join this conversation by sharing your thoughts in the comments section.

by Scott C. Alexander

I. Introduction

In some sense, this essay is a preliminary experiment in the application of an intersectional1 approach to the analysis of the history of anti-Catholicism and Islamophobia2 in the United States. It makes no pretentions at being definitive. Rather its aim is to offer a comparative analysis of these two phenomena in an attempt to suggest that a certain intersection exists between each phenomenon and the social construction of whiteness and the maintenance of white power and privilege in U.S. American history. The particular historiographical lens the essay employs to this end is an examination of two micro-historical moments or “seasons of discontent”—the summers of 1854 and 2010 and a triangulation of each with the recently concluded presidential election season of 2015-2016. The essay suggests that each of these micro-historical moments of exclusion intersects with a well-researched macro-historical narrative of systemic structures of whiteness/white supremacy3 and its attendant modes of racial oppression and marginalization. Its overall aim is to help broaden the discourse on the nature and causes of Islamophobia in the U.S. from a relatively narrow and historically myopic focus on its alleged root causes in acts of international and domestic terrorism since September 11, 2001, to include a more sustained consideration of the relationship of Islamophobia to an endemic “matrix of oppression”4 which has shaped, and continues to shape, so much of U.S. American history.

II. Two Seasons of Discontent: the Summer of 1854 and the Summer of 2010

The first two definitions of “discontent” in The Oxford English Dictionary indicate that—at the time of Shakespeare’s employment of the term in the opening lines of Richard III—the word denoted “strong displeasure” and “indignation,” especially in the sense of a “general dissatisfaction with existing social or political conditions.”5 Although in the play’s opening soliloquy, Gloucester (later Richard III), speaks of a “winter…of discontent” having been “Made glorious summer” by his brother’s coup, in the drama that follows this impending “summer” will prove to be at least as filled with “discontent” as its preceding “winter.”

Despite its sunny metaphorical connotation, the idea of a “summer” of discontent is not as counterintuitive as it may seem. Whether primarily due to the conduciveness of a balmier climate to outdoor activities, or the especially irritating effects of heat and humidity on already angry people, summers have often proven to be likely seasons for the “indignation” generated by “dissatisfaction with existing social or political conditions” to reach its fever pitch. One need only consider such momentous expressions of discontent in modern U.S. history such as the Watts Uprising of August 1965 or the momentous protest at the Democratic National Convention of 1968, just three Augusts later, as two cases in point.

What is key to recognize in all of this is that the circumstances of extreme—especially violent—manifestations of social and political “discontent” have little, if anything to do with the literal seasons of the solar year. Instead, they have a much broader and more complex temporal archaeology centered around “seasons” in the history of the U.S. American social and political psyche.

This was certainly the case in the summer of 1854 in Maine when a certain John Sayers Orr6 took his mission of preaching invective against the Catholic Church to the town of Bath. Known by the nom de guerre, “the Angel Gabriel” (allegedly because he would dramatically call people into his oratory orbit by the use of a trumpet), Orr incited certain citizens of Bath to rise up against the perceived Catholic threat and burn down the local Catholic church. The fact that this immigrant church had been established through the conversion of an abandoned settlers’ Congregational church no doubt added metaphorical fuel to what eventually resulted in a literal fire.7

This was also the case in the summer of 2010—when the headlines were filled with reports of other incendiary protests of both the figurative and literal type. Pastor Terry Jones caused quite a stir with an announcement that his Dove World Outreach Center in Gainesville, FL would mark September 11th, 2010 as “International Burn a Koran Day.” The nearly immediate, if not desired, effect of Jones’s announcement was not only an assault against the dignity of the faith of his fellow citizens who happen to be Muslim. Quickly achieving viral status on the Internet, Jones’s announcement placed U.S. troops occupying Muslim-majority societies in Afghanistan and Iraq at increased risk, not to mention further jeopardizing the vulnerable civilian populations of these societies who statistically suffer the most from the violence engendered by extremism of various types.

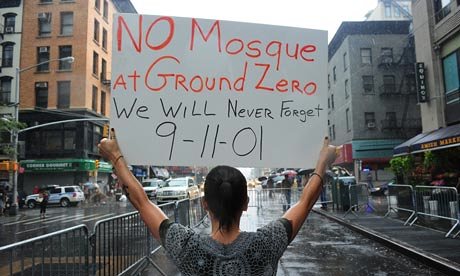

The summer of 2010 was also the same summer of the protests against the Lower Manhattan site of the Park 51 Project of the Cordoba Initiative, transposed into the false and deliberately misleading meme: “the Mosque at Ground Zero.” It was also during this same summer that, on August 28th, four mechanical excavators at the proposed new site for the Islamic Center of Murfreesboro, TN were doused with accelerant and one actually set on fire by an arsonist. This particular expression of “discontent” was the culmination of a series of speeches by local Tennessee politicians who, feigning due constitutional awareness, declared that most mosques were not places of worship, but breeding grounds for radical ideology and staging grounds for terrorist activities.8 Even televangelist and onetime presidential candidate Pat Robertson offered his ‘spiritual’ counsel on the matter by preaching to his audience: “You mark my word, if they start bringing thousands and thousands of Muslims into that relatively rural area, the next thing you know they’re going to be taking over the city council.”9

There is no doubt that the summers of 1854 and 2010 were quite literally two summers of “discontent” in U.S. American history. But, as Richard III ultimately reveals, the seasonal quality of social discontent—especially when such discontent takes the form of fear, hatred, and bigotry—has far less to do with the rhythms of the solar year, and far more to do with the nativist rhythms of our national psyche and mood. These seasons of nativist discontent can be identified as those days, months, years, decades, etc. when the background noise of our long, violent, seemingly interminable, and ultimately shameful macro-history of the struggle to preserve white power and privilege spikes in a relatively micro-historical intersection between real or perceived demographic shifts, on the one hand, and the symbolic power of the cycle of national observances like the 4th of July or a mid-term election, on the other.

III. 19th-Century Anti-Catholicism

The Bath arson took place on July 6th, 1854, just two days after the “Angel Gabriel” observed Independence Day by encouraging the vandalism of St. Anne’s Catholic Church in the largely Irish immigrant section of Nashua, NH known as the “Acre.”10 As is so often the case, this particular “season” of discontent far outlived the long days of that particular summer. It stretched into the autumn of that year and well beyond. In October, the seeds of hate and intolerance Orr had been planting throughout his New England tour yielded a robust fall harvest—once again, in Maine.

The distinguished historian John McGreevy grippingly describes the scene:

Near midnight, on Saturday evening, October 14, 1854, a mob of one hundred men in the small shipbuilding town of Ellsworth, Maine, attacked Fr. John Bapst, a Jesuit priest. Bapst had stopped in Ellsworth, hearing confessions for much of the day, en route to a sick call in a nearby town. Carrying lanterns and torches, the members of the mob surrounded the modest home of a Mr. Kent, an Irish immigrant, where Bapst was known to be staying. Kent at first denied that Bapst was inside. “We know he is, and we must have him,” yelled the mob. Bapst crept into the cellar of the home, closing a trap door behind him. Kent invited the mob to look in the windows. The mob would not relent. “If you don’t produce him we will burn down your house and roast him alive.”

Bapst emerged from the cellar to spare an attack on Kent’s home. According to one witness, he still hoped that the “instincts of humanity” would prevail, but the mob rushed upon him, dragged him one mile down the hill toward the Union River and tied him to a rail. Some in the mob advocated burning Bapst alive. The consensus was to tar and feather him, which the mob did, after stripping him naked, taking his watch and emptying his wallet. One eyewitness recalled plucking feathers from Bapst’s body after a search party had found him, then shaving off the priest’s hair and eyebrows to remove remaining bits of tar.11

John Hilling (1822 -1894), Burning of Old South Church, Bath, Maine, c. 1854, oil on canvas (Credit: National Gallery of Art)

Bapst escaped alive, but the country at large by no means escaped the hatemongering discontent expressed in Orr’s “ministry” and the propaganda of those who shared his perspective on the increasing Catholic presence on the social landscape of the United States. Indeed, in no way did the “Angel Gabriel” represent some lunatic fringe of mid-nineteenth-century U.S. nativism. No less than two years after the attacks in Maine, did a sitting member of the 34th U.S. Congress (representing the 5th District of New York/Manhattan)—Thomas R. Whitney12—publish a best-selling monograph warning of the impending dangers to the republic posed by the Catholic presence in the U.S.13

In this monograph, Whitney, who was a leading voice in the infamously anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic “American Party” (also known as the “Know Nothings”) has a chapter entitled “Papal Aspirations in the United States.” In this chapter Whitney focuses on “Jesuitism” as “the principal working element of the Church” which, he admonishes, “does not openly declare or make known its projects and purposes, until it is morally certain that all the rudiments of success have been perfected, and that a consummation is sure.”14 The “consummation” of which Whitney speaks is what he sees as the logical endgame of a faith tradition which, by its own admission, seeks to bring the entire world into its fold.

It would come as no surprise to any historian of U.S. Catholicism that Whitney was particularly concerned about the activities of the Irish-born Roman Catholic archbishop of New York, John Hughes. Hughes was a tireless advocate for the religious freedom of U.S. Catholics, who never shied from vigorous engagement in the public square in pursuit of his agenda. Hughes was known for debating noted Protestant clergy on questions such as “Is the Protestant religion the religion of Christ?” and “Is the Roman Catholic religion, in any of its principles or doctrines, inimical to civil or religious liberty?”15 In addition to being a prodigious fundraiser and supporter of numerous building projects for Catholic churches, hospitals, and schools in his diocese, Hughes was a gadfly on the horse of the Protestant establishment.

For example, based on his contention that Catholic school children were unfairly exposed to the ‘corrupted’ King James translation of the bible in the public school system—then funded by public monies administered by the private, Protestant-dominated Public School Society—he spearheaded a petition to the Common Council of the City of New York that Catholic schools be approved recipients of a percentage of the funding appropriated for the Public School Society.16 Hughes was also an ardent opponent of the expectation that U.S. Catholic parishes would increasingly ascribe to what the Catholic hierarchy referred to as “trusteeism”—a system of lay Protestant trusteeship over congregational funds designed to democratize local congregational governance by keeping the power of the purse ultimately out of the hands of clergy. Pursuant to a directive from Rome,17 all U.S. American lay Catholic parish boards were to cede ultimate authority over Church property, as well as the employment of priests, to the local bishop.18

With distinct anti-Catholic bias, but not without some provocation on the part of Hughes, Whitney and others saw Hughes’s agenda as part of an overall plan to overthrow the Protestant establishment—a nexus of institutions which the former were quite convinced was the spiritual and cultural backbone of the republic. In fact, Whitney alleges that Hughes once declared publicly that it was the intention of the pope to convert the president, members of Congress, members of the judiciary, members of the armed services, etc. to Roman Catholicism.19 Thus Whitney draws on the concerns of people like Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond and British “Governor of the Canadas” (1818-1820),20 and maintains in his book that such statements speak for themselves: Hughes and other Catholic leaders are clearly exposing the intent of the papacy is to transform the United States “into a papal nation and government.”21

Among other pieces of evidence that the Catholics are planning a deconstructive take-over of the U.S., Whitney points out that certain high government positions have now been occupied by Roman Catholics. The Roman Catholic Church has, Whitney argues, “obtained the control of our post-office department and secured the chief justice of the United States.” The chief justice to whom he refers is none other than Roger B. Taney.

The significance of Whitney’s anonymous reference to Taney cannot be underestimated, but not for the reasons one might immediately suspect. There can be little doubt it was seen as a critical data point for all those who shared Whitney’s fears of an insidious Catholic take-over of the republic. It also says something about the larger context of religious prejudice in mid-nineteenth-century U.S. American civic life: as strong as anti-Catholic sentiment undoubtedly was, it was not strong enough to prevent a Roman Catholic from becoming the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. It would be tempting to conclude that Taney’s 28-year tenure as chief justice—at a time when anti-Catholic fervor in the U.S. American body politic was at one of its highest points in history—speaks to a noble ability of the system to work “above” the prevailing prejudices of the day. One might even be tempted to contrast Taney’s historical context with our own and hypothesize how unlikely it would be that a Muslim be appointed to the Supreme Court (let alone become chief justice) in the post-9-11 U.S.

As incredible as it may sound, however, it would not be such a stretch to conceive of a Muslim’s being appointed to the Supreme Court, especially if that Muslim were thoroughly culturally assimilated. Imagine a Muslim jurist who happened to be a strict constructionist in method of constitutional interpretation. Now imagine this Muslim as either a woman who did not wear hijab or a man whose wife did not cover. Add to this, a penchant for being a sharp and outspoken critic of “radical Islam,” and an alignment with many items on the social and economic agenda of the conservative movement. This certainly would not be the first time in U.S. history that the prevailing system of power and privilege would welcome the advancement of an individual subaltern from a group of otherwise deliberately marginalized subalterns providing such advancement could somehow serve the interests of the dominant culture, especially by way of insulating this culture from the potentially dangerous critique that it is inherently exclusive and undemocratic and thus “un-American.”22

In Taney’s case, one of the major factors working in favor of his advancement was undoubtedly his close allegiance to his primary political patron—Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s passionate commitment to extend “freedom and democracy to even the poorest of whites”23 and the populist movement he led would ironically have been as attractive to immigrant Catholics as it would be to many of the plebeian Protestants likely to share Whitney’s anti-Catholic anxieties. Indeed, Jackson never seemed to try to hide his affinity for the Catholic community in the U.S. He likely never forgot the way in which Catholic New Orleans hailed him as the conquering hero of the republic in the immediate aftermath of his victory over the British in January of 1815.24 In all likelihood, Taney understood the significance and rarity of Jackson’s ability to lead a populist movement without an appeal to anti-Catholic nativism. Taney knew that it was no small thing when Jackson spoke of himself as a “lover of the Christian religion” but “no sectarian.”25 “I do not believe,” Jackson proclaimed in 1835, “that any who shall be so fortunate as to be received to heaven through the atonement of our blessed Savior will be asked whether they belonged to the Presbyterian, the Methodist, the Episcopalian, the Baptist, or the Roman Catholic [faiths]. All Christians are brethren, and all true Christians know they are such because they love one another. A true Christian loves all, immaterial to what sect or church he may belong.”26

An anti-Irish Catholic political cartoon by Thomas Nast

What Taney also understood, however, was Jackson’s commitment to preserving a union with a slaveholding South, and the degree to which an alliance with his powerful Catholic-friendly patron would ironically necessitate a compromise of his values as a Catholic. As a young Maryland lawyer acting as defense counsel for a Methodist minister charged with inciting slave rebellion in an abolitionist sermon, Taney once in open court denounced slavery as immoral. He was also known to have “quietly” manumitted his own slaves and even to have supported his older manumitted slaves by “giving them wallets for small silver pieces that he replenished every month.”27 In these ways Taney could be said to have embodied, especially in his private life, the abolitionist orientation that was becoming the dominant strain in Catholic teaching regarding the trafficking and holding of slaves.28

Taney’s jurisprudence from the bench of the Supreme Court, however, is quite a different story. As a son of a Mason-Dixon “border” state which was at once, the cradle of U.S. American Catholicism, staunchly slaveholding, and yet chose ultimately not to secede from the Union, Taney’s rulings as chief justice reflects a strong support, not only for the rights of slaveholders, but also for the rights of the slaveholding states to secede peacefully from the Union.29

Most significantly in this regard, Taney’s most memorable juridical legacy is as the U.S. Catholic jurist who authored the infamous 1856 majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford. In brief, Taney’s majority opinion denied that Mr. Scott had any constitutional standing as a citizen to sue his owner for emancipation. Using strict constructionist logic, Taney argues that the framers considered all black Africans to be “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect. …This opinion,” Taney maintains, “was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute; and men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted upon it in their private pursuits, as well as in matters of public concern, without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.”30

In the context of the famed Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln echoed the dissenting opinions of Justices Curtis and McLean. He did not so much challenge Taney’s strict constructionism as he challenged the historical accuracy of the latter’s assumption that the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the framers were unanimous in their allegedly implicit exclusion of black Africans from the privileges of citizenship, especially since, at the time of ratification of the Constitution, black men could vote in five of the Thirteen Colonies.31 Which raises the question as to why, if Taney did indeed harbor personal objections to slavery—likely rooted in his Catholicism—he wrote the opinion he did.

Although what I am about to suggest as an answer to this question is entirely impossible to substantiate with direct evidence, the circumstantial evidence involving the formative effect of his political alliance with Jackson and his unquestionable self-image as patriotic American Roman Catholic unionist in the Jacksonian mode is compelling. Although it would likely be just one of many factors shaping his decision, I nonetheless wish to raise the suspicion that Taney was, at least in part, demonstrating that a Catholic Chief Justice of the Supreme Court could decide an opinion in direct contradiction to the dictates of the Catholic faith. I wish to hypothesize the high probability that the Dred Scott decision was a product, not only of anti-black racism, but also of an eagerness for inclusion in the broader construction of normative “whiteness” which was threatening to exclude Catholics from the mainstream of U.S. civic life based on an allegedly superior loyalty to Rome over the republic, and which thus required bold proof to the contrary.

If such an hypothesis is reasonable—and I believe it is—then one can plausibly argue that the micro-historical season of discontent of the U.S. dominant culture with Catholics and Catholicism intersects with the macro-historical struggle over the social construction of white power and privilege in the U.S. and the country’s longstanding struggle over issues of national identity and race.

IV. Early 21st-Century Islamophobia

According to the Spring 2012 Intelligence Report of the Southern Poverty Law Center, 2010 was a banner year for Islamophobia, with a summer marked by a particularly intense rash of outbreaks.

“Anti-Muslim hate crimes soared by 50% in 2010 skyrocketing over 2009 levels (107 to 160) in a year marked by the incendiary rhetoric of Islam-bashing politicians and activists, especially over the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque” in New York City. …It was the highest level of anti-Muslim hate crimes since 2001, the year of the Sept. 11 attacks, when the FBI reported 481 anti-Muslim hate crimes. The year 2010 saw multiple verbal attacks on planned mosques, along with several violent attacks and arsons and the first attempts to ban Shariah religious law, even though the Constitution already precludes [such a ban].”32

In the presidential election of 1852 the Whig Party suffered a major defeat with the victory of the Democrat Franklin Pierce over the Whig candidate General Winfield Scott. Just two years later, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, thus vitiating the Missouri Compromise and allowing popular sovereignty to determine whether the Western Territories would allow slavery or not—considerably exacerbating the abolitionist/non-abolitionist divide and eventually contributing greatly to the disintegration of the Whigs and the de facto collapse of the so-called “second party system.” This collapse, in turn, opened up space on the American political landscape for the formation of new political parties, one of which was the party spawned by Thomas Whitney’s nativist anti-Catholic Order of United Americans: the “Know Nothings” who eventually became known as the American Party. The mid-term elections directly following the summer of 1854 (along with local and state elections in the following year) marked a bonanza for the new Know Nothing Party in which twelve governorships, one hundred Congressional seats and at least 1,000 other state and local legislative offices were secured by Know Nothing candidates.33

In the presidential election of 1852 the Whig Party suffered a major defeat with the victory of the Democrat Franklin Pierce over the Whig candidate General Winfield Scott. Just two years later, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, thus vitiating the Missouri Compromise and allowing popular sovereignty to determine whether the Western Territories would allow slavery or not—considerably exacerbating the abolitionist/non-abolitionist divide and eventually contributing greatly to the disintegration of the Whigs and the de facto collapse of the so-called “second party system.” This collapse, in turn, opened up space on the American political landscape for the formation of new political parties, one of which was the party spawned by Thomas Whitney’s nativist anti-Catholic Order of United Americans: the “Know Nothings” who eventually became known as the American Party. The mid-term elections directly following the summer of 1854 (along with local and state elections in the following year) marked a bonanza for the new Know Nothing Party in which twelve governorships, one hundred Congressional seats and at least 1,000 other state and local legislative offices were secured by Know Nothing candidates.33

Here is one of two striking similarities with the Tea Party Movement within the Republican Party in the mid-term elections directly following the summer of 2010. Although not a full-fledged political party, this movement backed a total of 138 Republican candidates “running for nearly half the Democratic or open seats in the House and a third of those in the Senate.”34 According to an NBC report issued the day after the election, 32% of all Tea party-backed candidates won seats in the U.S. Congress—five in the Senate and forty in the House.35 Although these numbers are far below the benchmark set by the Know Nothings in 1854, they are significant given that in 2010 there was no seismic shift in the party system proportional to the death of the Whigs in 1854, and given that the Tea Party was merely a “movement” which chose to graft itself onto the existing Republican Party.

The second striking similarity between the Know Nothings of 1854 and the Tea Party of 2010 is that both were largely white, populist movements which reflected, in their respective contexts, both a widespread disdain for legal and other structural changes designed to enhance the rights and status of the black population, on the one hand, and a strong nativism, on the other.

The relationship between mid-19th-century U.S. nativism and the slavery issue appears to be quite complex. In his landmark research, Tyler Anbinder has documented the significant degree to which Know Nothing rhetoric (at least in the North) linked Catholicism with slavery.36 Scholars have suggested, however, that this rhetoric tightly associating Catholicism with slavery may have been, at least in part, a disingenuous (with respect to abolition) political tactic on the part of the Know Nothings designed to reduce abolitionist fervor in the North and preserve the Union based on a common opposition to immigration.37 In other words, it was a way of appealing to Northern abolitionist sentiment to shift its focus onto immigration and concomitant Catholicization as a far greater threat to the republic, than slavery. The evidence appears to indicate that Know Nothings saw the immigration/Catholicization threat as the overriding threat around which the entire nation (North and South) could unite: in other words the Know Nothing message was simply that as terrible as slavery may be it is not something we should be quarreling about when the country is virtually being invaded by German and Irish Catholics! Perhaps this is part of the reason why, in their attempt to be unofficially reclassified as “white,” Irish Catholic immigrants followed the lead of Daniel “the Liberator” O’Connell and tried to keep the emphasis on abolition by strongly supporting the anti-slavery cause.38 Countering the Know Nothing narrative that they supported slavery would be one strategy U.S. Catholics could deploy to garner support among the northern Protestant abolitionists who might be susceptible to what Noel Ignatiev reminds us was the widespread speculation in the antebellum U.S. “that if racial amalgamation was ever to take place it would begin between those two groups [i.e., African American slaves and Irish immigrants].”39 The rationale here would be to convince the more socially progressive whites that the Irish were white in their fashion—opposed to slavery but supportive of racial segregation and thus staunchly opposed to ‘miscegenation.’

Were one retroactively to invent a Know Nothing slogan which parallels the famous unofficial Tea Party mantra “I want my country back,”40 it may simply be “Don’t let them take my country!” What the two share is an implicit (in the former) and explicit (in the latter) fear of a constructed economic, racial, and religious “they” who are poised to effect social change of a magnitude that threatens the power (im)balance—economic, racial, religious, and otherwise—of the status quo.

According to Dick Armey’s Tea Party Manifesto, published in the summer of 2010, Barack Obama’s “liberal” agenda to ‘apologize for the United States’ and “remake America” in order to create a ‘more just society’ is nothing less than a move toward an un-American, European-style ‘socialism.’ Liberals, Armey maintains, “prattle on about ‘social justice.’ They misuse the phrase. Justice means treating every individual with respect and decency and exactly the same as anyone else is treated under the laws of the land. As best we can tell, ‘social justice’ translates to really wise elected officials (you know, smarter than you) redistributing your hard-earned income to their favored social agendas, all dutifully administered by a well-intentioned bureaucrat.”41

On the issue of race, Skocpol and Williamson emphasize that, contrary to liberal stereotypes, it is grossly unfair to characterize all or most Tea Partiers as “unreconstructed racists—as people who react to politics and policy only through racial oppositions.”42 Yet if one were to distinguish between racism and personal bigotry such that the former refers to systems of structural injustice which can function independent of any conscious recognition of the latter among any particular set of white individuals, we get a somewhat different picture. The University of Washington’s 2010 Multi-State Survey of Race and Politics reveals that of the 45% of whites who either strongly or somewhat approve of the Tea Party movement, “only 35% believe Blacks to be hardworking, only 45 % believe Blacks are intelligent, and only 41% think that Blacks are trustworthy. Perceptions of Latinos aren’t much different. While 54% of White Tea Party supporters believe Latinos to be hardworking, only 44% think them intelligent, and even fewer, 42% of Tea Party supporters believe Latinos to be trustworthy.”43 As Skocpol and Williamson point out, a majority of mostly white Tea Partiers are quick to accuse fellow ‘entitled’ whites of many of the same character flaws to which the former would attribute the latter’s lack of success. “Tea Partiers,” they remind us, “have negative views about all of their fellow citizens; it is just that they make extra-jaundiced assessments of the work ethic of racial and ethnic minorities.”44

As for opposition to immigrants and immigration, Tea Partiers are apparently not as concerned with undocumented immigrants’ taking jobs away from citizens, or with the effects of widespread cultural change due to immigration, as were the 19th-century Know Nothings. Rather, “Tea Partiers regularly invoke illegal immigrants as prime examples of free-loaders who are draining public coffers. …Tea Party members,” Skocpol and Williamson report, “base their moral condemnation [of undocumented immigrants] on the fact that these are ‘lawbreakers’ who crossed the border without permission and thus are using American resources unfairly.”45

This seemingly important difference between the Tea Party and the Know Nothings when it comes to expressions of nativism, however, appears to evaporate almost completely when it comes to at least one category of immigrants and, incidentally, their indigenous African-American co-religionaries: Muslims.

Dick Armey’s Manifesto makes no explicit mention of Islam or Muslims and its only references to “terrorism” or “terrorists” come either with respect to the “eco” brand, or in an ironic defense against the slander of the left that the Tea Party is somehow related to the right-wing domestic form of “terrorism.” Nonetheless, ethnographic fieldwork reveals that, although Tea Partiers were generally loathe to express—at least openly—fear and hatred of African-Americans, Latinos/as, or other ethnic minorities, this was not the case when it came to Muslims as a religiously minoritized community. As Skocpol and Williamson’s research indicates,

This kind of prejudice was not invoked to talk about freeloaders or public spending but about terrorism and cultural change—even when the people being discussed were American citizens. Bonnie, for instance, said she had been hearing stories about “the Islamics [sic.] wanting to take over the country.” An Arizona Tea Party seminar on Islam was advertised as a way to “learn about the mindset of Muslims who follow these teachings and how the Islamic movement in our country has been affecting laws, culture, workplace, and teachings in our schools.” The seminar advertisement suggested that participants “START asking the tough questions about the teachings of Islam and the truth behind the acts of Islamic terrorism in our own backyard!” Even relative moderates are very worried about the threat posed by Muslims in America. “Most of them [Muslims] just want to practice their religion in peace,” Gloria explained to us. But she was also certain that some significant percentage wanted to impose “Sharia law” in the United States. We never got the sense, however, that any of our Tea Party informants actually knew any Muslim-Americans personally or even foreign Muslim visitors of whom they disapproved. Their statements and fears in this area were highly abstract.46

It is rhetorically tempting to say that the Islamophobia expressed by these Tea Partiers is “just the tip of the iceberg.” But this would imply that most of the Islamophobia in the U.S. exists “beneath the surface.” To the extent that this may indeed be the case, as it almost certainly is with anti-Semitism, then the “tip” of the Islamophobia iceberg is fairly massive. And, as noted in sec. 2 (above), eerily similar to the rash of anti-Catholicism in the summer of 1854, the summer of 2010 saw an outbreak of Islamophobic activity ranging from protests against a deceptively dubbed “Mosque at Ground Zero,” to a viral video (viewed by many in Iraq and Afghanistan) of a Christian pastor threatening to burn copies of the Qur’an to mark the ninth anniversary of the September 11th attacks, to an arson attempt against a mosque building site in Tennessee, and much more.

Anti-Muslim graffiti defaces a Shi’ite mosque at the Islamic Center of America in Dearborn, Michigan (Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

As was the case with the Bath, ME incident of 1854 and other public expressions of 19th-century anti-Catholicism, the public acts of Islamophobic “street” protests and “street” violence in 2010 were not without an entire network of support in the media, albeit far more extensive in forms and scope in 2010 than in 1854.

Among the more prominent counterparts of Thomas Whitney in this regard are writers and activists such as Robert Spencer, Aayan Hirsi Ali, and Pamela Geller. Contemporary Islamophobic “classics” such as Spencer’s The Politically Incorrect Guide to Islam (and the Crusades) which made the NY Times Bestsellers list in October of 200547 and his The Truth about Muhammad: Founder of the World’s Most Intolerant Religion (also a best-seller48), along with Ali’s more recent Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now (2015), claim that “Islam”—at least in its current form as the faith of 1.4 billion people—is severely flawed. These authors allege, as did Whitney with the Catholicism of his day, the essential illiberalism and bellicose nature of Islam which they decry as utterly incompatible—not specifically with U.S. American civic values as did Whitney—but with Western civilization and thus all true “civilization” as a whole.

Geller’s purview, on the other hand, is less a quasi-intellectual and pseudo-analytical attack on “Islam” as a deeply flawed tradition, although she frequently refers to this theme as presented in the works of Spencer, Ali, and the like. Instead, Geller’s primary focus—along with that of her Dutch counterpart Geert Wilders—is to echo Whitney’s concerns about the very real potential, if left unchecked, of the targeted Muslim out-group to destroy the culture of the in-group through a subtle but hostile takeover of the United States. One of the central admonitions of Geller’s project to “Stop the Islamization of America”49 and more recently “Stop the Islamization of Nations” (with the notable and troubling acronym, SION), is a very close analogue to Whitney’s admonitions regarding “Jesuitism.” It is her warning against “Shari’a Creep” or the eventual co-optation of the U.S. legal system—on both the local and national levels—by radical Islam and its domestic agents. This has led to a number of state legislative efforts to single out Islamic legal principles for inadmissibility in U.S. courts.50 Known as “ban Shari’a” initiatives, federal courts have unanimously struck them down as unconstitutional noting an absence of threat sufficient to suspend First Amendment protections of freedom of religion. Such rulings imply the discriminatory nature of such initiatives (why ban the admissibility of only Muslim religious norms from consideration in U.S. courts, for example, when enforcing wills and contracts?) as well as their superfluity (U.S. law supersedes any other legal norms which may conflict with its principles and statutes).51 These rulings have led some states—Alabama most recently—to retool such initiatives as bans on all “foreign laws” so as not to raise First Amendment objections by the federal courts.52

V. Lifting the Fog of History: Islamophobia, White Supremacy, and the Obama-Trump Dialectic

All of this amounts to what Nathan Lean53 and Wajahat Ali et al.54 have documented in their respective work, and what the former has aptly described as an “Islamophobia industry.” It goes without saying that, could he possibly imagine the scope of contemporary mass-media Islamophobia campaigns, Whitney would be green with envy at the sheer capacity of his late 20th-/early 21st-century Islamophobic counterparts to stimulate, feed, and mobilize sentiment against the ‘menacing’ out-group that is the target of their socio-political agenda.

But while vast and significant contextual differences between the anti-Catholic project of the mid- to late-19th century and the Islamophobic project of the late-20th/early-21st century abound, the outline of a distinct “matrix of oppression” appears to be emerging out of an historical fog, the eventual lifting of which is one of the primary objectives of this essay. This matrix has to do with the intersection—in the 18th century, in the current moment, and presumably at other moments in the intervening history—of anti-Catholicism, Islamophobia, and the social construction and maintenance of white power and privilege otherwise known as systemic racism.

My decision to employ the metaphor of an historical “fog” antedates, but has been considerably strengthened by, a stunningly brilliant homily preached by an academic colleague and friend of mine on the Sunday immediately following the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States.55 In this homily, Fr. Edward Foley, OFM (Cap.) made reference to a novel we had both recently read—Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant.

Foley recounts how the novel, “set in mythical post-Arthurian England” begins by introducing readers to the central pair of protagonists—Axl and Beatrice—an elderly couple who are suffering, along with everyone they know, from a barely perceptible loss of long-term memory. This gnawing communal amnesia, of which Axl is becoming increasingly aware, is not associated with dementia, but rather with a strange fog which has settled over the entire countryside sometime after the death of Arthur, who defended the Britons from the Saxon invaders and yet who somehow was able to establish a Briton-Saxon peace after the great bloodshed of the conflict between the two.

Through this mnemonic fog, Axl is able to remember a son who lives in a distant village and he manages to convince his wife to journey with him on a quest to reunite the family. Along the way the couple meets another pair: a Saxon warrior and an aging Briton knight and nephew of Arthur who gradually discover that they are mortal enemies, not despite, but precisely because of the nature of the Arthurian “peace” between their two peoples. We learn that this peace was not forged over time in the anguish-fueled furnace of truth and reconciliation, but rather almost instantly through the “magic” of a dragon whom Merlin enchanted to spew the fog of its amnesia-inducing breath over the very countryside that witnessed the horrors of Briton-Saxon warfare, and especially Arthur’s role as ruthless warlord and slaughterer of innocents. The Saxon has been charged with slaying the dragon, while the Arthurian knight is its sworn protector. Both eventually realize that the reason Axl was beginning to regain his memory is that the dragon was dying anyway.

In Foley’s words:

[The dragon’s] breath is the fog that induces this societal amnesia

dampening the memories of hatred and slaughter

Rivalry and division

that grew out of Arthur’s bloody conquest of the Saxons

And so there was a Camelot of sorts

But more a camelotic mask

A camelotic ruse

And once the dragon is slain

Memory returns …

A memory that will once again feed a smoldering anger

Between Britons and Saxons

And a memory that will feed smoldering doubts

Between Axl and his beloved Beatrice

Memory is the buried giant here

And when it raises its fiendish head

Personal division and societal chaos ensue.56

Foley goes on to compare the results of the 2016 presidential election to the slaying of the dragon. He offers the insight that the 16-month election season did not so much create as expose in bold relief profound pre-existing divisions in the body politic of the United(?) States. I agree with Foley, but wish to take this insight a few steps further. I want to suggest that even a brief examination of the Trump phenomenon reveals the ways in which these profound pre-existing divisions are evident in the intersectional connection between anti-Catholicism, Islamophobia, and white supremacy at the focus of this essay.

At one time I supposed that, were Barack Obama a Roman Catholic (rather than a Protestant) Christian, there would be no more explicit instantiation of the particular matrix of domination I am attempting to identify in this essay than the so-called “Birther” Movement. Led by Donald J. Trump—and thus part of the larger multi-dimensional dynamic of what I am referring to as the “Trump phenomenon”—the agenda of Birtherism was to question the legitimacy of Obama’s presidency by calling into question his religion and nationality. I supposed that the dogwhistle rhetoric of a Black Catholic’s ‘actually being a Muslim’ and (thus) ‘not a real U.S. American’ would be a stark indication that the recipe for the Birtherism stew was at least: “place one part anti-Catholicism, one part Islamophobia, one part white supremacism into a crock pot, blend vigorously and allow to simmer for quite some time.”

Deeper consideration, however, reveals that Obama’s identity as a Black Protestant may be the key to understanding the precise degree to which the Birtherism stew, and thus the wider Trump phenomenon, has white supremacy as its bouillon, and anti-Catholicism and Islamophobia, respectively, as the primary ingrédient de la saison. Ironically, Obama’s identification with a Kingian tradition of Black liberationist Protestantism—a tradition which has relentlessly insisted on holding a mirror up to a sinful republic marred by the atrocities of genocide, chattel slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, the Vietnam War, and mass incarceration—makes him far more a contemporary counterpart of the ‘subversive’ 19th-century Catholic immigrant than were he himself a Black Catholic, and thus a subaltern within what has unquestionably become the white-dominated U.S. Catholic Church of the late-20th and early-21st centuries.57

As one writer for The Washington Times58 points out in an Op-Ed piece published a few months after Obama’s inauguration, Obama’s having once been a member of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Jr.’s Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago is just the tip of the iceberg. Below the surface looms the ‘threat’ of leading African American theologians like James Cone and his particular brand of “black liberation theology” which, the writer is quick to point out, is viewed by “many black pastors” as “a misguided if not aberrant form of Christianity.”59 The author of this piece questions the veracity of Obama’s claims to be unaware of all of the statements of Rev. Wright. “But,” he argues,

it is likely that Mr. Obama knows about the philosophy, principles, values and teachings of black liberation theology, which is the foundation of his church — the wellspring from which Mr. Wright’s divisive rhetoric flows. Mr. Obama’s veracity and integrity, or at least his judgment, will be subject to question if he denies having detailed knowledge of black liberation theology. And if he knows about the movement, why would he align himself and his family with such a theology for some 20 years? … If Mr. Obama wants to be the leader of all Americans, he must clearly and decisively separate himself not just from Mr. Wright, but from black liberation theology and those churches and pastors that preach it as truth. Why he hasn’t done so is a question that still has been neither asked nor answered.60

The two lines of this quote that I have chosen to emphasize in italics speak volumes. The first posits a mutual exclusivity between a commitment to the insights and vision of black liberation theology, on the one hand, and being “the leader of all Americans,” on the other. The second sets the stage for the Birther Movement, by suggesting that Obama—by virtue of his being a black Protestant with liberationist leanings—cannot possibly be a ‘real’ American, let alone a legitimate president.

The distance between the final question posed by this Op-Ed writer and the claim that Obama may not even be a Christian is minimal. Indeed, from one popular perspective within the matrix of white supremacist domination, Obama’s connection with black liberationist Protestantism situates him at odds with normative (read “white”) U.S. American Christianity, and thus renders him nearly indistinguishable from those other brown and black folk who, on the basis of another ‘anti-Christian’ and thus equally ‘subversive’ and ‘anti-American’ ideology masquerading as a prophetic religion, point to the sins of the United States and seek to do it harm: Muslims.

It also did not take long for the vague insinuation that Obama was a crypto-Muslim to make it from the pen of a rather obscure “senior risk management consultant in homeland security… with a master of divinity in biblical studies” writing for The Washington Times, to that of Dinesh D’Souza, current president of The Kings College of New York City and one of the leading conservative ideologues on the U.S. American scene. Noteworthy for his South Asian heritage, a Christian identity comprised of a Catholic background and Evangelical churchgoing, and his singular role as an apologist for Western European colonialism,61 D’Souza claims to have had “a kind of epiphany” after reading Obama’s Dreams from My Father:

I was struggling to reconcile Obama’s self-presentation as an African American with his father’s experience as an anti-colonialist from Kenya. How, I wondered, could the son’s experience and the father’s dream fit together? Then it hit me. The son’s account of his own experience was largely bogus. Obama never sat at a segregated lunch counter, and neither did any of his ancestors. He is not descended, as most African Americans are, from slaves. In fact, his accounts of prejudice in his autobiography are very slight and, it turns out, largely made up. In fact, the son’s formative experiences in Hawaii, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Kenya very closely track the anti-colonial journey of his father, and thus there is no conflict to be resolved. The son consciously chose to make himself in the image of his father, just as he tells us in his book.62

D’Souza goes on to claim that, once he donned his “anti-colonial spectacles,” he began to understand “literally everything about Obama.”63 He skillfully—albeit disingenuously—distances himself from any conspiracy theorizing that Barack Obama is actually a Muslim. He even professes to resist any suspicion that Obama consciously construes his political and social agenda to be “anti-American.” Yet, at the very same time he sympathizes with those who believe that Obama is “anti-American” and a “closet Muslim.” What else, he implies, are many Americans to think of a president who wants to “shrink America’s global footprint, to cut America down to size” and who “views Muslims who are fighting against America in Iraq and Afghanistan as freedom-fighters, somewhat akin to Indians or Kenyans fighting to push out their British colonial occupier.”64 With little effort in decoding required, it becomes obvious that what D’Souza is saying is that Obama is not a Muslim, but he might as well be.

If there are any doubts that this is D’Souza’s thesis, one need only consider the thinly encoded title of the book in which he paints his portrait of Obama as a notorious “anti-colonialist”: The Roots of Obama’s Rage. Although, to the best of my knowledge, D’Souza assiduously avoids making any explicit reference to the inspiration behind his title, it is quite obvious to those familiar with the architecture of late 20th-century Islamophobic “scholarship.” In 1990, Princeton University’s Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies, Bernard Lewis, published his Jefferson Lecture of the same year as the cover essay of what is now an (in)famous edition of The Atlantic Monthly. The original title of the lecture was the rather innocuous sounding “Western Civilization: A View from the East.” The title of the Atlantic piece was far more honest, and thus far more expressive of the patent Orientalist bias of which Edward Said had so pointedly accused Lewis some twelve years earlier65: “The Roots of Muslim Rage”—complete with cover art featuring a cartoon of a scowling, hulking, black-bearded, Central-Asian looking and turban-sporting figure which would rival the skill and effect of any of the anti-Semitic cartoons of Nazi Germany, not to mention those of the U.S. American cartoons of the ‘Jap enemy’ from the same era.66

If there are any doubts that this is D’Souza’s thesis, one need only consider the thinly encoded title of the book in which he paints his portrait of Obama as a notorious “anti-colonialist”: The Roots of Obama’s Rage. Although, to the best of my knowledge, D’Souza assiduously avoids making any explicit reference to the inspiration behind his title, it is quite obvious to those familiar with the architecture of late 20th-century Islamophobic “scholarship.” In 1990, Princeton University’s Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies, Bernard Lewis, published his Jefferson Lecture of the same year as the cover essay of what is now an (in)famous edition of The Atlantic Monthly. The original title of the lecture was the rather innocuous sounding “Western Civilization: A View from the East.” The title of the Atlantic piece was far more honest, and thus far more expressive of the patent Orientalist bias of which Edward Said had so pointedly accused Lewis some twelve years earlier65: “The Roots of Muslim Rage”—complete with cover art featuring a cartoon of a scowling, hulking, black-bearded, Central-Asian looking and turban-sporting figure which would rival the skill and effect of any of the anti-Semitic cartoons of Nazi Germany, not to mention those of the U.S. American cartoons of the ‘Jap enemy’ from the same era.66

That the Lewis essay inspired Huntington to write his “The Clash of Civilizations?” article some three years later,67 and that the so-called “Huntington thesis” (in the form of a monograph of the same title, but sans question mark) became the virtual manifesto of the neo-conservative foreign policy of the George W. Bush Administration toward the Muslim-majority world and especially the Middle East, is not directly pertinent to this essay. What is pertinent, however, is that D’Souza clearly triggers the “Obama-as-crypto-Muslim” meme in the very title of the book in which he declares his clear conviction that Obama is not actually a Muslim.

In The Roots of Obama’s Rage, D’Souza speaks as a brown, South Asian, naturalized immigrant, and ‘son of Western colonialism,’ who argues that Obama is not really African American at all, but rather more of an alien “anti-colonialist.” In one stunningly counter-intuitive act of typological legerdemain, D’Souza attempts to: transform “anti-colonialist” from a morally positive to a morally negative descriptor; render “African American” a descriptor and identity upon which Obama has no authentic claim (and thus conveniently irrelevant to D’Souza’s ipso-facto ‘non-racist’ critique of Obama); and to maintain “Muslim” as a category of dangerous ambiguity, open for his readers to populate with bloodthirsty foreign “anti-colonialists” like Obama and his Kenyan father, friendly brown patriotic South Asian neighbors not unlike himself, or some combination of the two.

Despite his obvious intelligence and professed aspirations to take the unpopular moral high ground against various forms of liberal political correctness, it is difficult to see D’Souza as anything but a master of inventing and peddling—under the guise of high-minded polemic—a panoply of pseudo-sophisticated dog whistles for those of his readers whose self-image is rooted in the conviction that it is not they who participate in, benefit from, and sustain systemic racism, but rather that is they who are fast becoming the victims of a creeping liberal agenda rooted in a self-loathing anti-white “racism” of its own.68

Just as there were few more skilled than Dinesh D’Souza at providing the necessary rhetorical code for the more high brow elements of the systemic racist attempt to delegitimize the first African American president, no one was more aware of the political liabilities of being the black man (especially the “angry” black man), the Muslim (especially the “angry” Muslim), or both, than Barack Obama himself. This astute awareness, combined with his signature pragmatism, led Obama to make two closely related moves when it came to his identity. The first was his disavowal of the Rev. Jeremiah Wright (mentioned above). The second was his staunch refusal, until the eleventh hour of his presidency, to be ‘caught’ on camera in a domestic (i.e., non-diplomatic) visit to a Muslim house of worship.69 Obama wanted to be perceived as the least possible “angry” black man and least possible Muslim man. Indeed, on those occasions—mostly during his first presidential election campaign—when he did choose to address the question as to whether or not he were a Muslim, Obama shied away from his otherwise cherished role of Civics-Teacher-in-Chief. For fear of what he thought might be unsustainable political damage, he would typically reply by denying that he was, and/or by asserting his Christian identity. What he never did, at least publicly, is respond by asking the most important questions—especially from the perspective of his Muslim American constituents: “And so what if I were? Why should this even matter in a country which prides itself on its uncompromising dedication to freedom of religion?”

The only prominent figure who actually did pose these critical questions in a national forum was leading Republican and former Secretary of State Colin Powell who broke party ranks to endorse Mr. Obama in a Meet the Press interview with Tom Brokaw on 19 October 2008. Referring to the pervasive nature of the “Obama-as-crypto-Muslim” meme in Republican Party rhetoric, Powell expresses how disturbed he is by

…what members of the party say. And it is permitted to be said; such things as, “Well, you know that Mr. Obama is a Muslim.” Well, the correct answer is, “He is not a Muslim, he’s a Christian. He’s always been a Christian.” But the really right answer is, “What if he is? Is there something wrong with being a Muslim in this country?” The answer’s “No, that’s not America.” Is there something wrong with some seven-year-old Muslim-American kid believing that he or she could be president? Yet, I have heard senior members of my own party drop the suggestion, “He’s a Muslim and he might be associated terrorists.” This is not the way we should be doing it in America.70

That Colin Powell makes this bold statement in the context of his endorsement of Barack Obama over John McCain is highly suggestive. At the time of the endorsement, Powell was something of a Republican Party luminary, having distinguished himself as the first and only African American to serve both as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (1989-1993) and Secretary of State (2001-2005). In the Brokaw interview, immediately after confirming his support for Obama, and a few minutes before his comments on Obama’s religious identity, Powell sets the larger frame for why he has decided not to endorse McCain whom he describes as a “beloved friend and colleague.” “I have some concerns,” Powell says, “about the direction that the party has taken in recent years.” To what, exactly, is Powell referring? Powell begins his explanation by expressing vague misgivings about McCain’s lack of “a complete grasp” of economic issues and clearer misgivings over McCain’s choice of Sarah Palin as his running mate. But this appears to be merely the prelude to his principal concerns. “The approach of the Republican Party and Mr. McCain,” Powell observes, “has become narrower and narrower. Mr. Obama, at the same time, has given us a more inclusive, broader reach into the needs and aspirations of our people. He’s crossing lines—ethnic lines, racial lines, generational lines.”71 And then, almost immediately before his comments about Obama’s religious identity, Powell raises the issue of the McCain campaign’s focus on Obama’s relationship with Bill Ayres as part of an overall strategy to insinuate that Obama has “some kind of terrorist feelings.”72

Although he is careful to avoid any explicitly accusation of “racism,” it is difficult not to conclude that Powell decided to reject his longtime friend and party precisely because of the extent to which they had opted to suborn brazenly the national narrative of white supremacy. Indeed Powell’s comments about the insinuations that Obama is a Muslim appear to be rooted in the former’s awareness of a deeper connection between being black and being Muslim in the United States—a connection which Powell seems to recognize as extending well beyond the demographic that “among the roughly one-in-five Muslim Americans whose parents also were born in the U.S., 59% are African Americans, including a sizable majority who have converted to Islam (69%). Overall, 13% of U.S. Muslims are African Americans whose parents were born in the United States.”73 Powell appears to be painfully cognizant that this connection lies in the fact that, like the Catholic immigrants of the mid- to late 19th century, both black Americans and Muslim Americans were and are viewed as potential subversives to the republic and the white power and privilege it was designed to protect and perpetuate.

The contrast between Powell’s statement on Meet the Press in the context of the 2007-2008 presidential election season, and that of another prominent African American appearing on the same show within the context of the 2015-2016 presidential election season, could not be starker. On Sunday, 20 September 2015, host Chuck Todd asked leading pediatric neurologist and then Republican presidential primary candidate Dr. Ben Carson whether or not he thought Islam was “consistent with the [U.S.] Constitution.” Carson’s response was a blunt, “No, I don’t. I do not,” after which he immediately volunteers: “I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation. I absolutely would not agree with that.”74

Less than three months later, Trump, then Carson’s primary opponent whom he would later endorse for the presidency, called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.”75 Despite the usual disclaimer of ‘love’ for Muslims issued by most mainstream purveyors of Islamophobic stereotypes and propaganda, Trump has certainly established formidable Islamophobic credentials. He has done this, not only by virtue of his own characteristically incendiary remarks76 (by no means uniquely targeting Muslims), but also by his appointment to his inner circle, advisors who are themselves leading contributors to Islamophobic discourse in the U.S. American context. Particularly noteworthy among these are General Michael T. Flynn, Trump’s original but short-lived appointee as national security advisor; Steve Bannon, the president’s chief political strategist (at least as of the publication of this essay); and the lesser known Sebastian Gorka who carries the title of “Deputy Assistant to the President.”

Flynn is on record declaring that Islam—not “Islamism” as he later(?) emends his rhetoric—“is a political ideology. It is a political ideology. It definitely hides behind this notion of it being a religion.” Flynn goes on to compare the religion of approximately 1.6 billion human beings to a deadly disease: “It’s like cancer. I’ve gone through cancer in my own life. And so it’s like cancer. And it’s like a malignant cancer, though, in this case. It has metastasized.”77

Bannon is far more strategic in the application of Islamophobic rhetoric than Flynn. Instead of “Islam,” he ironically adopts the slightly more politically correct (at least by so-called “alt-right” standards) use of “radical Islam,” “radical Islamic terrorism,” or some variant thereof. Apparently influenced by a combination of Lewis/Huntington’s “Clash” thesis and Straus and Howe’s exercise in a popular apocalyptic version of pseudo-historiography, Bannon insists on emphasizing the “Islamic” nature of the extremist political ideologies of phenomena such as ISIS because to do otherwise would not comport with his favorite version of a global historical master narrative. The point of stressing that ISIS and al-Qaeda are “Islamic” is precisely to counter the narrative that extremist groups which attempt to assert their legitimacy by waving the banner of political Islam are actually seen as horribly aberrant by the vast majority of Muslims. According to the Bannon master narrative, were such an inherently non-apocalyptic view to gain traction, the United States would be susceptible to the fatal ‘delusion’ of concluding that these groups are not the ultimate existential threat to the United States and the “West” that they claim to be. If this were to happen, the danger becomes all too real that the ‘rise of secular individualism’ (and especially ‘liberalism’) and ‘the rise of (anti-colonial) Islam’ in the ‘Fourth Turning’78 of American history, will be victorious in destroying the United States as we know it.

As for Gorka, his negative essentialist view of Islam as an inherently violent religion is evident in his typology of the historical evolution of what he refers to as the “seven swords of jihad.”79 A largely derivative hybrid of the work of Efraim Karsh80 and the “Green Peril” school of neoconservative foreign policy,81 Gorka’s thesis supports Bannon’s apocalyptic narrative and implies that “Jihadism” is the next great totalitarian threat to humanity—a threat which can only be thwarted by United States in the same way that it thwarted the last great totalitarian threat of Soviet communism.

At the time of writing this essay, a number of U.S. Federal District Courts have blocked both of President Trump’s executive orders banning travel from specified Muslim-majority countries. Although the legal arguments are beyond my capability to analyze, one of the common threads in each of these decisions to stay the orders has been the courts’ inability to ignore the First Amendment ramifications of some of the things candidate Trump said while on the campaign trail—in particular his December 2015 call for a temporary ban on Muslim immigration to the U.S. This suggests that the Islamophobic bias and agenda of the Trump Administration is meeting with at least some institutional resistance on the part of the judiciary.

Many perceive such judicial resistance, combined with widespread grassroots protests and activism, as the basis for a pragmatic hope that the Trump narrative of white nationalism may yet fail, and that the white populist policy agenda of the new administration is by no means a fait accompli. Too few, however, appear to be asking what the potential of such hope is as long as using expressions such as “Trump narrative of white nationalism” and “white populist policy agenda” continues to be branded as ‘reverse racist’ rhetoric of the radical left rather than categories of analysis rooted in a methodologically legitimate read of U.S. history. Let us imagine, for example, a hypothetical situation in which the majority of white Americans who were disappointed in the results of the last presidential election are somehow exposed to Michelle Alexander’s description of the current system of mass incarceration of men of color as the “new Jim Crow.”82 Would they be more likely to perceive her language as hyperbolic or critically accurate? Although there is no way of knowing the answer to this particular question, a combination of anecdotal evidence and statistical research revealing huge gaps between what black and white U.S. American adults think about the level of racist oppression faced by blacks in the United States suggests that there is a strong likelihood that a sizeable percentage of whites—including many who would identify as ‘anti-Trump’—would be inclined to dismiss Alexander’s language as more hyperbolic than critically accurate.83

I would argue that my educated guess in this regard is further supported by the fact that Trump’s calculated, well-funded, and well-orchestrated attempt to move Birtherism into the political mainstream seems to have had a relatively minor effect on his celebrity status, especially when compared to other white celebrities who used the N-word or made other egregious and blatantly racist or sexist remarks.84 It is not unreasonable to speculate that had Trump been ‘caught on tape’ using the N-word—rather than lending his persona and financial resources to one of the most overtly racist political movements since the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 60s—NBC may well have been forced to cancel The Celebrity Apprentice, thus considerably compromising his celebrity status, access to media, and perhaps even potential as an upset candidate in the 2015-2016 Republican Presidential Primary. Instead, the season of The Celebrity Apprentice which opened March 2011—the very same month in which Trump began to appear on major television networks questioning, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, the birthplace and thus the legitimacy of the nation’s first African American president85—was the highest rated season of the show in six years.

The lesson here has sadly become something of a truism among most experts in racial theory and race relations in the United States: as long as the vast majority of leading voices in mainstream political, civic, religious, and media fora, are willing to identify and denounce racism only when it takes the form of facilely verifiable verbal expressions of personal bigotry or prejudice and hardly ever in its far more pernicious encoded systemic manifestations, the ‘hope’ placed in the significant resistance to the latest (i.e., Trumpian) versions of white nationalism and white supremacy will prove as hollow as such hope has been in the past.

IV. Conclusion: Whither the Catholics?

Now that I have lamented over the reality of so many hopes for racial justice proving hollow in the past and potentially once again, I wish to close by cautiously intimating what might be different this time around. Just as I have described the analysis of the history of anti-Catholicism and Islamophobia in this essay as intersectional insofar as it triangulates on the matrix for oppression known as “whiteness” or “white supremacy,” this very same word is one heard more and more frequently these days on the lips and even in the brief online biographies of social-justice activists.86 As one seasoned African American Muslim community organizer who works on Chicago’s Southside told a class on interfaith community organizing we taught together last semester: “A lot of us—the black community, the Muslim community, the Latino/a community, the LGBTQI community—were complacent during the Obama years because we assumed, wrongly or rightly, that we had an ally in the White House. Now that we know this is definitely not the case, the energy level—particularly for building coalitions—is higher than I’ve ever seen it.”87 Although this remains to be documented in any reliable way, the intersectionality of the grassroots resistance to the policy agenda of the Trump administration may one day prove to be the highest to date on record in U.S. history.

One somewhat hopeful dimension of this intersectionality which is particularly relevant to the focus of this essay, involves certain very recent developments in institutional Catholic-Muslim relations in the U.S. Nearly twenty years ago, what is now the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops began to partner with U.S. Muslim organizations such as the Islamic Society of North America, the Islamic Circle of North America, and the Islamic Center of Orange County, CA to co-sponsor three robust annual regional dialogues.88 Although these dialogues have produced useful documents89 and, more importantly, have served as contexts for forging lasting relationships of mutual understanding, trust, and friendship between scores of Muslim and Catholic scholars and religious leaders, there has been relatively little energy on the Catholic ‘side’ to address, in any sustained and public way, the social sin of Islamophobia here in the U.S. The one notable exception to this came in the aftermath of this essay’s second “season of discontent” (i.e., the Summer of 2010) when Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, by then Archbishop Emeritus of Washington, D.C., responded to the call of Muslim leaders and decided to lend his articulate voice and enthusiastic support to the Shoulder-to-Shoulder Campaign, an interreligious coalition formed for the purposes of “standing with American Muslims” and “upholding American values.”90

That the U.S. Catholic bishops and most Catholic dioceses and congregations have on the whole been reluctant or outright opposed to partnering with Muslims in order to challenge the social sin of Islamophobia should come as no surprise, especially in light of our intersectional analysis of the history of Islamophobia and the fact that, as Massingale persuasively argues, there has been a proportionately anemic response of the U.S. Catholic bishops and faithful to the broader scourge and social sin of white supremacy.91 Put quite simply, the logic of this essay’s analysis indicates that insofar as the U.S. Catholic Church has been and continues to be a “white racist institution,” as Massingale defines it,92 it is improbable that it would mobilize and partner with Muslims to fight Islamophobia.

My own experience in the regional dialogues for the past sixteen years has confirmed this improbability. That is, at least until the recent presidential campaign season and election. Unquestionably influenced by what we might look upon as this essay’s third “season of discontent,” a newly conceived and instituted National Catholic-Muslim Dialogue which, at one point, appeared to be headed in the direction of more benign neglect of the pressing issue of Islamophobia in favor of high-level theological exchange and scripture study among credentialed scholars93 made an abrupt turn.

My own experience in the regional dialogues for the past sixteen years has confirmed this improbability. That is, at least until the recent presidential campaign season and election. Unquestionably influenced by what we might look upon as this essay’s third “season of discontent,” a newly conceived and instituted National Catholic-Muslim Dialogue which, at one point, appeared to be headed in the direction of more benign neglect of the pressing issue of Islamophobia in favor of high-level theological exchange and scripture study among credentialed scholars93 made an abrupt turn.

It was at the inaugural meeting of the National Catholic-Muslim Dialogue in early March of 2017 at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, that I recall hearing for the first time Catholic bishops, not only use the term “Islamophobia,” but identify Islamophobia as an ominous reality—a sin against which U.S. Catholics must stand in solidarity with their fellow citizens, and especially with their Muslim sisters and brothers.

One of the leading voices in this regard was the newly appointed Catholic co-convener of the national dialogue, Cardinal Blase Cupich, the Archbishop of Chicago, who issued a letter in the immediate aftermath of the issuance of President Trump’s first executive order banning travel to the United States from seven Muslim-majority countries. In his letter, Cardinal Cupich offers an uncompromising moral critique of the discriminatory nature of the travel ban, which he introduces with a powerful historical reflection:

This weekend proved to be a dark moment in U.S. history. The executive order to turn away refugees and to close our nation to those, particularly Muslims, fleeing violence, oppression and persecution is contrary to both Catholic and American values. Have we not repeated the disastrous decisions of those in the past who turned away other people fleeing violence, leaving certain ethnicities and religions marginalized and excluded? We Catholics know that history well, for, like others, we have been on the other side of such decisions.94

Another leading Catholic voice in the dialogue and its call to fight Islamophobia was that of the episcopal moderator of the West Coast Catholic-Muslim Dialogue, Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego. McElroy devoted a good deal of his public keynote address at the dialogue to the problem of Islamophobia and the imperative that Catholics stand up and be counted as resisting its structures and effects. McElroy insisted that Catholics “condemn unequivocally” anti-Muslim prejudice. In the spirit of remarks he made one month prior at the World Meeting of Popular Movements (02.28.17) where he spoke about the need to become “disrupters” of narratives of hatred, marginalization, and oppression,95 McElroy declared it “unconscionable that in the United States, in the 21st century, one of the great world religions is caricatured, misrepresented and despised so widely in our culture. It is even more appalling that Muslims have now become the object of government actions, carefully and deliberately designed in laws to target a specific religious community.”96

Despite what some conservative U.S. Catholics might maintain about the demonization—much of it real—of the Catholic Church by the political left, it is safe to say that this is no longer the 1850s. According to the FBI’s 2015 Hate Crime Statistics, by far the majority of reported religiously motivated hate crimes were a result of anti-Jewish bias at 52.1% (of the total 1,402), with anti-Muslim bias ranking second at 21.9%, and anti-Catholic bias ranking a very distant third at 4.3%.97 Although these statistics are just one indication, by most accounts the majority of non-Latino/a and non-black Catholics in the U.S. inhabit and are the beneficiaries of, as Massingale points out, white privilege. From the perspective of Catholic social teaching, the only just use of social privilege of any kind is to deploy it for the expressed purpose of realizing the radical mutuality of all relationships characteristic of the inner nature of the Triune God and the nature of God’s reign.