Seth Dowland (Pacific Lutheran University) responds to Russell Johnson’s (University of Chicago) essay, “The Struggle Is Real: Understanding the American ‘Culture War,’ ” which is featured in the July issue of the Forum. Three recent books all claim the culture war is over, though they come to different conclusions about why. Their different points, this essay argues, illustrate not why the culture war is over, but rather why it is so endlessly fascinating. In response to these books, this essay clarifies what exactly the culture war is, and how to understand in what sense it is still a part of American life. The culture war brings together a diverse array of political, religious, and cultural ideas into a neat dichotomy that has managed to persist through decades of social change.

Throughout the month, scholars will offer responses to Johnson’s essay. We invite you to join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.

Responses:

- Andrew Hartman (Illinois State University), “Culture Wars and Other Subterranean Historical Forces“

- Seth Dowland (Pacific Lutheran University), “Where are the Culture Wars?“

- L. Benjamin Rolsky (Monmouth University), “American Cultural Warfare and the Recent Religious Past“

- Russell Johnson, “Author’s Response: War forms Its Own Culture“

Where are the Culture Wars?

by Seth Dowland

In his recent essay “Why I Went Back to Church,” Max Perry Mueller details his journey back to the church after the election of Donald Trump. He hoped church would be a place “to reforge the bonds of community.” He admits arrogance in thinking his interpretation of the gospel—which focuses on caring for the needy and modeling a gentler masculinity—would sway his fellow white Christians to reject Trumpism. Mueller realizes the deficiency of his own Manichean thinking that divided the world into good and evil. His fellow churchgoers—even those “evil” folks who voted for Trump—are actively engaged in resettling refugees. In short, going to church has, for Mueller, punctured the logic of the culture wars, which depend on a highly polarized narrative of America.

Yet Mueller’s church-driven epiphanies have not thawed the relationship between him and his Trump-supporting father. The two men have not talked since Thanksgiving. Mueller hopes—but does not know—that Christian forgiveness might one day reconcile his father and himself. The culture wars, it’s obvious, remain potent.

I had Mueller’s piece in mind as I considered Russell Johnson’s provocative and thoughtful essay, “The Struggle is Real.” Johnson challenges three quite disparate books’ conclusions that the culture war is over. To the contrary, Johnson argues that the culture war narratives still dominate Americans’ sense of themselves and their country. Johnson’s essay weaves social psychology and rhetorical theory with historical review, providing a textured account of why the culture wars are so persistent.

But Mueller’s essay calls into question the ubiquity of the culture wars. In particular, it suggests that the culture wars operate in certain contexts but not others. For him, the culture wars divide his family but not his church. The language of sin, grace, and baptism supersede the polarities of politics and culture, at least for a few moments each week.

Recognizing areas where the culture wars subside can spark hope. But the conclusion to Andrew Hartman’s A War for the Soul of America, which Johnson deftly analyzes, argues that another antidote to the culture wars has been capitalism, which has cynically commodified dissent and blithely marginalized tradition. To combatants on either side of the culture war divide, the triumph of the market has cheapened American culture.

One pressing question emerging from these observations is this: how do we move beyond the framework of the culture wars?

Johnson’s essay grapples well with each of the three books under consideration, even as it collapses some of their methodological differences. Dreher writes as an apologist for (lower-case o) “orthodox Christianity”; Gorski as a sociologist; and Hartman as a historian. These methodological approaches shape the valence of their conclusions. It’s not quite enough to say each author believes the culture wars are over. Johnson’s careful critique of each book demonstrates his methodological dexterity, yet his conclusion elides the books’ different approaches in order to make their diagnoses of our current political moment converge—at least rhetorically. But Dreher’s lament about the end of the culture wars is quite distinct from Hartman’s historical analysis! The former fears the tyranny of secular liberalism, while the latter cautions about corrosive capitalism.

Johnson hints at these differences in his conclusion, where he commends the three authors as “helpful to the extent that they envision ways to go on” beyond the culture wars, noting that their prognoses for moral action diverge. I would push this further. Dreher enjoins conservative Christians to turn inward, cultivating lives and communities marked by deep discipleship. Hartman, on the other hand, historicizes the most recent incarnation of the culture wars, calling out the historical ironies that marked their demise and signaling to liberals the ways in which their causes became co-opted. Gorski’s more optimistic frame diagnoses Americans as not nearly divided as culture warriors would have it, and he encourages centrists to reclaim the “righteous republic.” In short (and with crude oversimplification): Dreher thinks the liberals won; Hartman argues capitalism subsumed both sides; and Gorski pleads on behalf of the vital center.

The divergent approaches and conclusions of the authors under review led me to wonder what was at stake for Johnson: what does maintaining the dominance of the culture war narrative do for us? Johnson argues that “anyone hoping to make moral arguments in contemporary America” needs to account for the culture wars in their arguments. But as Johnson concedes, the culture wars both obscure and limit moral arguments. In one of the most fascinating sections of his essay, Johnson details how “the culture war is primarily a media phenomenon.”

Popular media have significant power, but there are places in contemporary America, like religious organizations, neighborhoods, and schools, where the logic of the culture wars need not predominate. Churchgoers might find the liturgy superseding politics; neighbors might model radical hospitality; classrooms might be spaces of common learning. I use the subjunctive “might” here because I know how naïve such hopes can sound. And yet: the culture wars can fade from view in each of the three institutions I name here.

Making moral arguments that move beyond the culture wars demands good faith and shared commitment to the common good, which is why it’s nigh impossible in Washington, D.C., or on social media. These spaces shape our lives dramatically. Anyone hoping to make moral arguments about the meaning of America in Congress or on Twitter must take heed of Johnson’s cautions about the persistence of the culture war.

It’s my hope—and Johnson’s, too, I think—that we might find powerful antidotes to the culture war narratives that so decisively shapes our politics. Doing so will require us to ignore, suspend, or at least minimize the operating logic of the culture wars. We will need to assume that we’re on one team or ten teams—not just two. We will need moral narratives drawn from liturgies and classic texts, narratives that ground us in a history that preceded the culture wars. And we will need to understand the powerful forces that push us towards culture war polarities.

Johnson wants us to see that the “struggle is real,” but he also wants us to move beyond the battles we’ve been fighting fruitlessly for decades. The irony is that doing so might force us to places where the culture wars seem least powerful—places where we can pretend the struggle isn’t so real after all. ♦

Seth Dowland is Associate Professor of Religion at Pacific Lutheran University, where he teaches courses on Christianity, Islam, gender, and politics in U.S. religious history. His first book, Family Values and the Rise of the Christian Right (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), examines the historical development of a “family values” agenda among conservative evangelicals in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. He has published several articles on the history of Christianity in the United States. He is currently working on his second book, Purity and Power: A History of White Christian Masculinity in America.

Seth Dowland is Associate Professor of Religion at Pacific Lutheran University, where he teaches courses on Christianity, Islam, gender, and politics in U.S. religious history. His first book, Family Values and the Rise of the Christian Right (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), examines the historical development of a “family values” agenda among conservative evangelicals in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. He has published several articles on the history of Christianity in the United States. He is currently working on his second book, Purity and Power: A History of White Christian Masculinity in America.

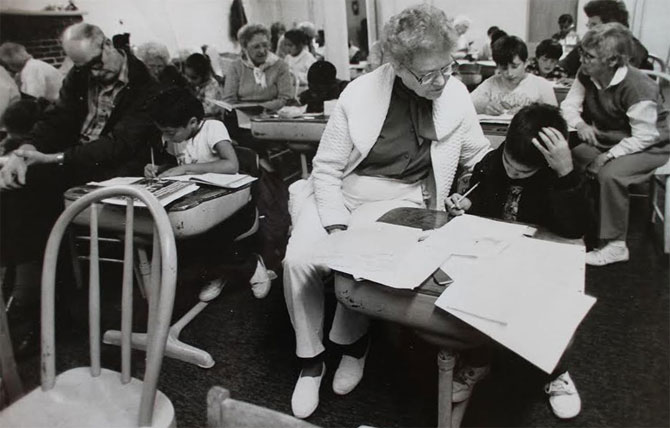

* Feature image: A neighborhood after-school tutoring program (in the 1980s) at the author’s current church. Click here for more on the story of the congregation.