Philippa Koch (PhD ’16) joins our scholars’ roundtable on healthcare and religion with her essay, “‘The seeds of compassion and duty’: An Early Americanist Take on Healthcare.” The September issue of the Forum explores the place of religion and the academic study of religion vis-à-vis the healthcare debate. In light of Congress’s ongoing effort to reform the US healthcare system, we have invited a handful of scholars of religion to discuss the role of religion in the broader national conversation about health and healthcare as well as the potential contribution(s) of scholars of religion to this national dialogue. We invite you to join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.

Posted essays:

- Mark Lambert (University of Chicago), The Trump Administration, Immigration, and the Instrumentalization of Leprosy

- Courtney Wilder (Midland University), Disability Theology and the Healthcare Debate

- Philippa Koch (Missouri State University), “The seeds of compassion and duty”: An Early Americanist Take on Healthcare

- Raymond Barfield (Duke University), To Reimagine Healthcare, We Must Remember Who We Are

by Philippa Koch

In December of 1775, a Massachusetts woman named Molly Forbes discovered a hard spot under her nipple. She was treated with a plaster, revealing an ulcer. This was a second occurrence, and the hardness had spread throughout her breast and into her glands. Continued treatment with plasters offered some relief. Her health nonetheless worsened, and she died in January, leaving behind young children and a grief-stricken husband. There is no record of the cost or payment for her care.1

In December of 1775, a Massachusetts woman named Molly Forbes discovered a hard spot under her nipple. She was treated with a plaster, revealing an ulcer. This was a second occurrence, and the hardness had spread throughout her breast and into her glands. Continued treatment with plasters offered some relief. Her health nonetheless worsened, and she died in January, leaving behind young children and a grief-stricken husband. There is no record of the cost or payment for her care.1

Last January, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had felt no lump; it was detected at a routine mammogram. She had a successful lumpectomy. The laboratory analysis, however, revealed a microscopic amount of cancer had spread into a node. She began chemotherapy, followed by radiation. Her prognosis is good. Medicare and a purchased supplemental plan cover her medical expenses.

It is hard to fathom what early Americans would think about healthcare today.

Medicine has changed greatly, and much of the industry around medicine, including health insurance, did not exist in the eighteenth century. We share experiences of embodiment and pain with people in the past, but I try not to elide the significant differences. We cannot assume a common, transhistorical experience of suffering and its meaning—or of the demands of human life and human care.

So, what do we share with early Americans? How can they help us think about the current healthcare debate? Despite our considerable distance, I would argue that we share something significant: a sense of duty to care for the suffering. A community cared for Molly Forbes; a community is caring for my mom.

Today, we don’t hear much about the social duty of providing healthcare, yet it seems to me that it’s the heart of the matter. You might hear healthcare described as a right, but a commitment to rights depends on duty; our society has a duty to further the conditions that make possible individual rights. For early Americans, the sense of duty to relieve suffering came from a variety of perspectives. “Duty” evokes the sense of calling or mission found among eighteenth-century Protestants. Duty also stemmed from Enlightenment-era conceptions of sensibility and the sympathy it engendered; the ability to “feel another’s pain” and the desire to relieve it were seen as crucial to both human reason and the progress of society. Many early Americans grounded their sense of duty in both religion and reason.2

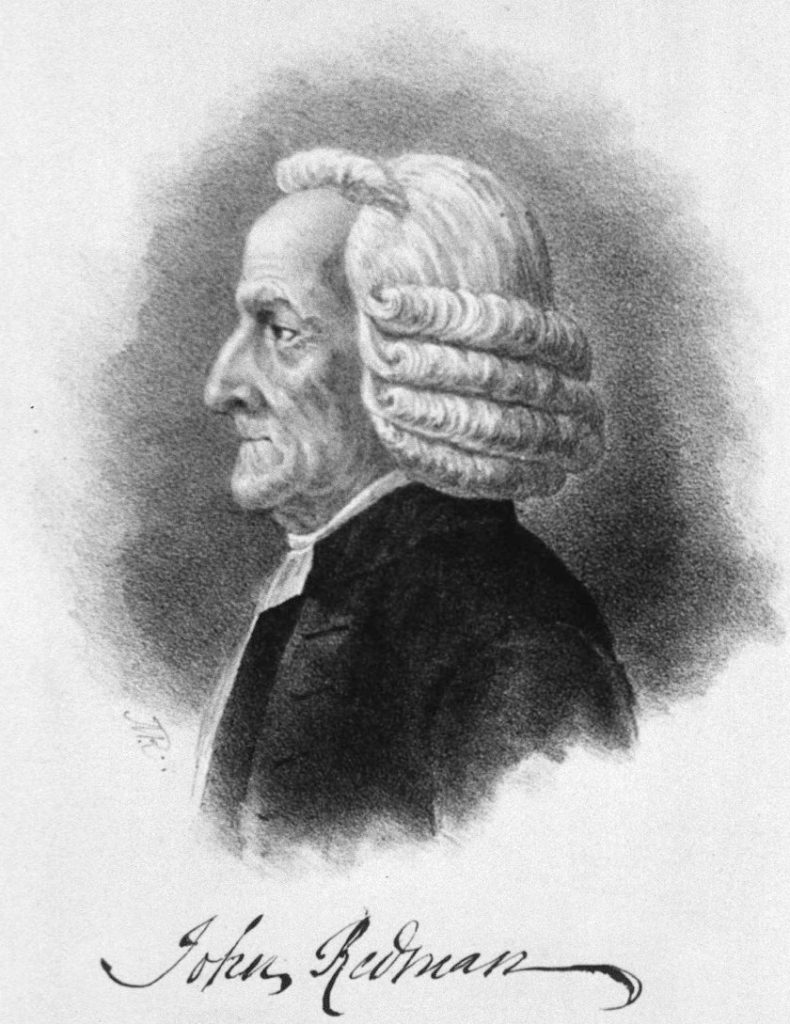

John Redman (February 22, 1722 – March 19, 1808)

Take, for example, the physician John Redman, who in 1787 became the first president of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, America’s first professional medical society. He was also a devout Presbyterian and mentor to Benjamin Rush. Redman’s Calvinist faith informed his practice and his sense of duty. He longed to “serve our generation faithfully according to the will of God” and described God’s direction throughout “the voyage of life.”3

Redman’s understanding of duty also reflected an Enlightenment-era emphasis on rationality that rooted conceptions like sympathy and benevolence in human reason. Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid described benevolence as a virtue when developed from reason: a “fixed purpose or resolution to do good when we have opportunity, from a conviction that it is right, and is our duty.” Redman celebrated such benevolence among his fellow physicians, urging the College to the “cause of humanity,” and toasting the “individual practitioner, who makes the health, Comfort, & happiness of his fellow Mortalls one of the chief Ends and delights of his life.”4

Like Redman, many early Americans found their sense of duty informed by both a Christian calling and Enlightenment-era ideas of humanity. The Puritan Cotton Mather and the Methodist John Wesley saw medicine as a gift from God to be developed and shared to alleviate human suffering. German Pietists made medicine a central part of their missionary efforts.5 During the Yellow Fever epidemic in 1793 Philadelphia, African American nurses described their work as a duty forged by feelings of fellow humanity as well as their sense of God’s presence.6 A committee of Philadelphians, meanwhile, reorganized the hospital and cared for orphans, citing God’s direction and a “duty incumbent” for those “humanely disposed” to care for fellow citizens.7

This sense of duty to relieve suffering also grew from lived experience. Americans today generally expect to “feel good” most of the time; early Americans were more likely to experience sickness as the norm and health as the aberration. The constancy of sickness confirmed their theology and view of society. They saw sickness as an inevitable part of the human condition—a result of original sin. As John Wesley wrote, “the seeds of weakness and pain, of sickness and death are . . . lodged in our inmost substance.” Or, as Cotton Mather explained, “We all deserve to be sick.”8

For early Americans, the recognition of the universal reach of sickness was more important than fixating on any individual’s moral culpability. Today when sickness is associated with sin it is usually done on a superficial level, such as arguing that some people are more deserving of care than others because of previous health, financial, or so-called “lifestyle” choices.9 Early American Christians saw health as given by God on God’s terms and not based on human merit. You could not moralize your way to perfect health.

You still can’t.

Sickness knows no boundaries. For the people I study, what mattered was the response to sickness and finding a duty—rooted in faith, reason, and experience—to alleviate suffering.

Today, we continue to rely on multiple sources of duty and the language of duty when we choose to help people: many Americans do have a sense of shared vulnerability grounded in experience. Others rely on our common humanity and sympathy, our religious convictions, our concern for civic cohesion and order, our interest in cleanliness and public health, or our desire for social progress. We haven’t always thought critically about our social duty to provide healthcare, leading to concerns that government has become too paternalistic in providing healthcare. There have been and will be missteps in our pursuit of care, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have a conversation about duty. In fact, that means we should have a conversation. While we may not always agree on the motivating factors, we must recognize the care for others as a common enterprise, to pursue in ways that do not discriminate or harm.

One way we don’t differ greatly from early Americans is in how devastating illness can be. In early America, physical suffering affected every aspect of human life, from economic opportunities and education to family life and gender roles.10 The defining and far-reaching effects of physical suffering remain today. We have incredible medical research and treatment possibilities, accessible and clean hospitals, and trained medical practitioners. Yet people still suffer, and sometimes they suffer because they are unable to access affordable healthcare or are forced to make difficult decisions between health and debt. As in early America, ill health today can define your life: your career, your identity, your opportunities.

Health is essential to full participation in civil society; this was a major impetus for Medicare and Medicaid legislation. These programs, alongside medical developments, have made possible wide-scale alleviation of suffering in ways that would have been unimaginable to early Americans. When Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law in 1965, however, his rhetoric recognized antecedents. He praised his predecessor Harry Truman, “who planted the seeds of compassion and duty which have today flowered into care for the sick, and serenity for the fearful.”

Medicare and Medicaid were born from compassion and duty, from “the piercing and humane eye which can see beyond the words to the people that they touch.” Johnson’s words came from a history of enlightened humanitarianism, from lived experience, and, finally, from scripture. He quoted Deuteronomy 15:11, explaining that the tradition to care “is as old as the day it was first commanded: ‘Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor, to thy needy, in thy land.’”11

Remembering that early Americans approached healthcare as a duty to others, grounded in diverse sources, doesn’t provide easy answers for our present moment. But it does offer an avenue for progress in healthcare debates: most Americans today still feel some duty—even if our sources are ever-more diverse. The current conversation is expanded and deepened when we think about this duty alongside rights, and such reframing also offers new resources for persuasion in calls for fuller coverage. It helps balance the story, reminding us of what is, after all, a crucial part of the health/care equation: the care of the community for the health of all. ♦

Philippa Koch (PhD ‘16) is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Missouri State University, where she teaches courses on religion in America, health and the body in American religions, and sexuality and religion. She is currently revising her book, “Persistent Providence: Healing the Body and Soul in Early America,” for publication, and her work has previously appeared in Church History, Notches, The Atlantic, and Sightings. Her article, “Experience and the Soul in Eighteenth-Century Medicine,” Church History (2016) received the Sidney E. Mead Prize from the American Society of Church History. Her research has been supported by the Charlotte W. Newcombe Foundation, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, the Martin Marty Center, and the Francke Foundations in Halle, among others.

Philippa Koch (PhD ‘16) is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Missouri State University, where she teaches courses on religion in America, health and the body in American religions, and sexuality and religion. She is currently revising her book, “Persistent Providence: Healing the Body and Soul in Early America,” for publication, and her work has previously appeared in Church History, Notches, The Atlantic, and Sightings. Her article, “Experience and the Soul in Eighteenth-Century Medicine,” Church History (2016) received the Sidney E. Mead Prize from the American Society of Church History. Her research has been supported by the Charlotte W. Newcombe Foundation, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies, the Martin Marty Center, and the Francke Foundations in Halle, among others.

* Feature image: Robert A. Thom, “Benjamin Rush: Physician, Pedant, Patriot.” 1959.

- Eli Forbes to Ebenezer Parkman, 17 January and 2 March 1776, Parkman Family Papers, Box 3, Folder 3, American Antiquarian Society. ↩

- Carolyn D. Williams, “‘The Luxury of Doing Good’: Benevolence, Sensibility, and the Royal Humane Society, in Pleasure in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Roy Porter and Marie Mulvey Roberts (New York: New York UP, 1996), 86-90. ↩

- John Redman, M.D., 1722-1808: First President of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, compiled and edited by William N. Bradley, (Philadelphia, 1948), 114-118. Originally published as: “The Inaugural Address, Made to the College of Physicians, by the First President Thereof, Dr. John Redman,” in The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, ed. W.S. W. Ruschenberger (Philadelphia: 1887), 179-183. John Redman to Benjamin Rush, 21 December 1782, Rush Family Papers, Library Company of Philadelphia, volume 22, page 21. ↩

- Thomas Reid, Essays on the Intellectual and Active Powers of Man (Philadelphia: Young, 1793), volume 2, 227-236. These volumes were first published in the 1780s in Scotland. John Redman, M.D., 199-200. ↩

- Philippa Koch, “Experience and the Soul in Eighteenth-Century Medicine,” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 85 (September 2016): 552-586. ↩

- A(bsolom) J(ones) and R(ichard) A(llen), A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon them in some late Publications. (Philadelphia: Woodward, 1794). ↩

- Committee to Attend to and Alleviate the Sufferings of the Afflicted with the Malignant Fever, minutes, 1793-1794, Library Company of Philadelphia. ↩

- John Wesley, Primative (sic) Physic; or an Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases, 16th ed. (Trenton, NJ: Quequelle and Wilson, 1788), iii-iv. This book went through 23 editions before Wesley’s death in 1791, and 37 editions total before 1859; Deborah Madden, ‘A Cheap, Safe, and Natural Medicine’: Religion, Medicine, and Culture in John Wesley’s Primitive Physic, Clio Medica 83 (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2007), 11-12; Cotton Mather, Wholesome Words: A visit of advice, given unto families that are visited with sickness (Boston: Henchman, 1713), 5-10. ↩

- See, for example, Jonathan Chait, “Republican Blurts Out That Sick People Don’t Deserve Affordable Care,” New York Magazine (1 May 2017), http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2017/05/republican-sick-people-dont-deserve-affordable-care.html; Andrew P. Napolitano, “Is health care a right or a good?” FOX NEWS (30 March 2017), http://www.foxnews.com/opinion/2017/03/30/is-health-care-right-or-good.html; Trump’s language on banning transgender people from the armed forces makes an implicit (and insidious) moral equation between their identity and their potential to “disrupt” the armed services, alongside a highly disputable claim about their higher healthcare costs. Jeremy Diamond, “Trump to reinstate US military ban on transgender people,” CNN (26 July 3017), http://www.cnn.com/2017/07/26/politics/trump-military-transgender/index.html. ↩

- Elaine Forman Crane, “‘I Have Suffer’d Much Today’: The Defining Force of Pain in Early America,” in Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, ed. Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, and Fredrika J. Teute (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997): 370-403. ↩

- Lyndon B. Johnson, “394 – Remarks with President Truman at the Signing in Independence of the Medicare Bill. July 30, 1965.” The American Presidency Project, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=27123&st=&st1. ↩