In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, urban planning became increasingly important as architects began to pay more attention to the design of a city as a whole, instead of simply considering important buildings. Two urban planning movements are particularly significant, and are important contributions to the history of urban planning in the context of modern architecture: the garden city movement, and Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago.

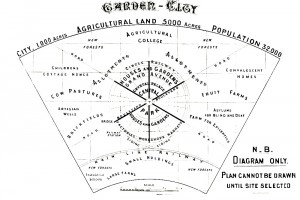

In the nineteenth century, with the rise of industrialism and manufacturing in the United Kingdom, private companies sought new ways to increase productivity and profits, while architects desired a new way to live, away from the perceived degraded and unhealthy lifestyle of the city. One solution to these problems was the Garden City Movement inspired by rural British living, which tried to design living areas meant to be idyllic and removed from the dirty cities. 1 Spearheaded by architects such as Ebenezer Howard, John Ruskin, and William Morris, the garden city was meant to be built for companies and provide living and working areas for employees. Companies attempted to improve productivity through better living conditions. These conditions included wider streets with varying fronts, gardens and community space, and employment and production within the garden city itself, with no need for commuting.2 Figure 1 is Ebenezer Howard’s theoretical drawing of a model city, and illustrates how the city was meant to be designed; it is clear that the city is closely related to, and embedded in, nature. The Garden City Movement is an early example of architects attempting to improve working-class people’s lives through redesigning the urban environment.

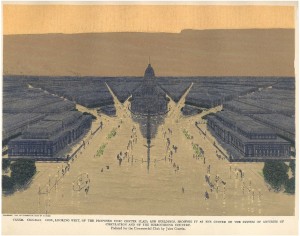

In the early twentieth century, Daniel Burnham conceived of a design for the future of Chicago. He, like the architects involved with the Garden City Movement, was concerned with the state of the urban environment and believed Chicago’s urban design and planning could be improved to better benefit its citizens. In 1909 Burnham created the Plan of Chicago, which outlined his idealized version of the city. The Plan focused on several major aspects of the city: improving the lakefront and an expanded park system, creating a highway system, and improving street arrangement and the railway system.3 Figure 2 is an illustration of Burnham’s vision. Such a design was meant to provide vast public spaces, and generally improve the livability of the city, as Carl Smith writes that “Chicago suffered from being a place where all too many people came to work and invest rather than to live.” 4 This sentiment, as Smith describes, is reflective of the beliefs of an elite business class, Burnham included, that Chicago can and should be improved to become larger and grander. 5 Such beliefs manifest a criticism of urban planning, that urban planning is simply an act of an elite class, with little regard for history or the general public. Regardless of any criticism, after Burnham’s death and the onset of the Great Depression, few of the original plans were implemented. As an example of urban planning, the Plan of Chicago is grand in design, but proved unrealistic in practice.

These examples of urban planning are similar and different in many ways. Each design concerns itself with the improvement of social conditions through physical changes to the built environment, though the Garden City Movement accomplishes this through an idyllic English aesthetic and Burnham does this through a more classical, monumental approach. Similarly, these designs may be interpreted as elitists imposing structure on lower classes; the Garden City Movement was designed to be optimized for profit, and Burnham’s Plan, through its association with business and social elites, appears equally concerned with grandeur as it does with functionality. These examples illustrate the potential benefits and criticisms of urban planning in the context of modern architecture.

-JH

Notes:

Figure 1: Jules Guerin, View Looking West of the Proposed Civic Center Plaza and Buildings. Public domain. Available at Wikimedia Commons, link (accessed November 24, 2015).

Figure 2: Ebenezer Howard, A General Plan for a “Garden-City.” Public domain. Available at The University of Adelaide, link (accessed November 24, 2015).

- Linda Hall, “Garden Suburbs: Architecture, Landscape and Modernity 1880-1940,” The Victorian Web. Accessed on November 3, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Carl Smith, “An Excerpt from The Plan of Chicago,” University of Chicago Press. Accessed on November 3, 2015. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Michael P. McCarthy, “Chicago Businessmen and the Burnham Plan,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 63, no. 3 (1970): 228-256. ↩