Frida Plata, Student, MA Program in the Humanities (MAPH)

In order to study Mesoamerican art, we must frequently ask ourselves an important question – what elements can we derive from the objects themselves, and what are we deriving from our imagination to fill in the gaps of knowledge? The buildings and art of Chichén Itzá can help us consider how the imagination fills knowledge gaps, especially for a discipline like Mesoamerican art history that requires a substantial amount of information derived from the object itself. Close looking of the objects at Chichén Itzá helps us to reconsider posited theories about the site’s art and architecture, especially because of the limited primary sources available to us about Chichén Itzá. Much of the site’s documentation was destroyed by Diego de Landa (a Spanish Bishop who proselytized to the locals and helped colonize the region) upon his arrival during the sixteenth century. So, the codices that would have helped us decipher Mayan script have left us with many unanswered questions about the history, architecture, and art of Chichén Itzá [1]. Still, despite our limited primary sources, Chichén Itzá’s remains provide the visual information that can allow us to decipher the site’s meaning and aesthetic contributions to Mesoamerican art. In the fall of 2019, the Art History department offered a traveling seminar, led by Associate Professor Claudia Brittenham, to conduct the close looking necessary to reconsider methodological approaches taken thus far toward investigating Chichén Itzá and Mesoamerican art.

One different methodological approach when examining Chichén Itzá’s material evidence includes re-visualizing the site through the eyes of other artists. One artist in particular, American photographer Laura Gilpin, captured images of Chichén Itzá that allow us to see the complex designs of the site’s art and architecture. In 1932, Gilpin captured the first important documented photograph of the Castillo before sunset during the equinox [2] (Fig. 1). The north side of the Castillo depicts a serpent made from light and shadow that appears to slither down the pyramid’s west balustrade. This sophisticated projection of the great “Plumed Serpent,” an important supernatural figure in Mesoamerica, just begins to demonstrate Chichén Itzá’s sophisticated and fascinating architecture.

Figure 1. Laura Gilpin, Steps of the Castillo, Chichen Itza, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 35.4 x 26.7 cm

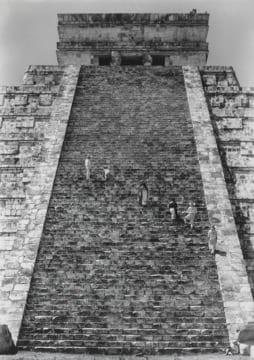

Another one of Gilpin’s significant images of the Castillo is Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan (1932) (Fig. 2). The photograph depicts six people scaling one of the Castillo’s stairways at Chichén Itzá. Even though the Castillo technically has four stairways, Gilpin features only one of the stairways in her photograph, thus simplifying the use of the space and eliminating any other possible processional pathways leading to the temple that sits on the ninth (and last) platform at the top of the building. From the top of the building to the bottom of the stairway, Gilpin photographs the Castillo from a centralized low angle, making the stairs seem gargantuan and thus seeming to create a monument of the Castillo while also adding a sense of drama to the long and steep trek to building’s entrance. Despite the elaborate, open-mouthed serpent heads on either side of the stairway entrance, Gilpin crops out most of the serpent heads from the photograph, emphasizing the stairway in the photograph more than any other architectural or ornamental feature of the Castillo.

Figure 2. Laura Gilpin, Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 34.5 x 24.3 cm

As one moves their eyes towards the top of the Castillo’s stairs, they notice the temple’s entrance, awaiting the people scaling the stairs to enter it. The temple’s entrance appears perfectly aligned with the stairway, emphasizing a centrality and symmetry in the photograph. Symmetry and centrality are further emphasized by the design of the temple itself—two rounded columns evenly divide the temple’s entryway and help to unify the symmetry of the photograph.

One can also note the symmetry in Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan by the linear repetition throughout the photograph. For example, the repeated horizontal pattern of the stairs helps to emphasize the symmetry of the photograph as the pattern takes up the center of the page. In addition to the repeated horizontal linear patterns in the photograph, the vertical lines that comprise the balustrades also play an important role within the photograph. The vertical lines in the image not only frame the symmetry of the repeated pattern of the stairs, but these vertical lines contribute to the monumentality within the photograph. They provide a sense of stability and strength to the image, much like the rounded columns at the temple’s entrance also provide a sense of stability, strength, and monumentality to the photograph. With the way that Gilpin utilizes line repetition to frame the stairway that leads to the temple, in addition to the people scaling the stairs that look toward the temple’s entrance, we are compelled to consider what resides beyond the temple’s doorway. Though one can visibly see the doorway’s entrance at the top of the stairs (as this photograph was captured during the day), they cannot see within the building because it is concealed in complete darkness. Still, even though we cannot see inside the building, we cannot help but wonder how the Maya utilized the space within and what they conceived when they were constructing the Castillo.

Regarding the people photographed in this image, they all wear seemingly traditional Maya dress. The women in the image appear to wear huipiles, the traditional white and embroidered dress of Maya women, their skirt hems decorated with detailed embroidery [3]. The men wear huaraches and straw sombreros (though short pants and tunics are more common), providing some shade against the strong Yucatec sun as they scale the Castillo’s steep stairway. As these people scale the stairs, their bodies create a diagonal line across the stairway, breaking the centrality and symmetry of the photograph. The young boy sitting and leaning against one of the serpent heads at the end of the balustrade at the bottom of the stairway also functions within the image in a similar manner, breaking the symmetry in the photograph as he sits alone, observing the others scale the Castillo’s stairs. In addition to breaking the centrality and symmetry within the photograph, the diagonal line created by the people in the photograph gives the image a sense of action and dynamism, which contrasts the stability provided by the horizontal linear repetition of the stairs and the vertical repetition of the balustrades.

Upon actually seeing the Castillo during the traveling seminar, we realized just how the ancient Maya strategically employed certain optical illusions to emphasize the pyramid’s monumentality. For example, the area surrounding the Castillo remains empty, thus making the Castillo appear much larger than the other buildings distantly placed from the pyramid. In addition, the Castillo itself incorporates an optical illusion of sorts in its design. As one moves their eyes form the bottom to the top of the pyramid, they can observe that the squares on each platform incrementally decrease in size toward the top, thus making it seem as if the Castillo is much larger than its somewhat modest size, especially compared to other pyramids in Mesoamerica (such as Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Moon and the Great Pyramid of Cholula in Puebla). Naturally, actually being able to visit Chichén Itzá through this traveling seminar opened up many more questions about this fascinating site. It will certainly continue to perplex and fascinate art historians as we continue to investigate and uncover its meanings.

Footnotes:

[1] Linnea Holmer, et al., Lanscapes of the Itza: Archaeology and Art History at Chichen Itza and Neighboring Sites (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018), 37.

[2] John B. Carlson, “Pilgrimage and the Equinox ‘Serpent of Light and Shadow’ Phenomenon at the Castillo, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán,” Archaeoastronomy: The Journal of Astronomy in Culture 14, no. 1 (1999): 138.

[3] Phillip Hofstetter, Maya Yucatán: An Artist’s Journey (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009), 107.