Laura Colaneri, PhD Candidate, Romance Languages and Literatures

In an elegant apartment in Madrid in 1971, several prominent Argentines held vigil over an old and battered, but still preserved, corpse. Missing for 14 years, the embalmed body of Eva Perón, Argentina’s widely beloved first lady from 1946–1952, had finally been returned to her husband, the former Argentine president, General Juan Perón, who was living in exile with his new wife, Isabel. Upon its arrival, they had laid it out on a marble table on an upper floor. Isabelita spent days cleaning the dirt from the disinterred body, washing, drying, and brushing out its hair.1 The cadaver’s presence in the house, one of the other Argentines claimed, would help to fortify Isabel and give her the deceased’s strength. Evita’s spirit would enter into Isabel’s body and work through her, with his help. He conducted rituals to aid the transference of the deceased spirit into the body of the living, making Isabel lay down head to head with the corpse as he passed his hands over her and intervened with the spiritual world. Jorge Paladino, an Argentine politician, later claimed to have witnessed this scene, calling it a session of “magia negra.”2

These spiritual sessions were conducted under the influence of the Peróns’ private secretary, José López Rega, whose esoteric beliefs and practices would earn him the nickname of el Brujo, the sorcerer. Only a few years after these rituals held over Evita’s body, he would become the most powerful man in Argentina, reviled and feared for his role in directing a right-wing paramilitary group, the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (AAA), in activities that included the murder, disappearance, and forced exile of thousands of Argentine citizens. These actions characterized a bloody period of state-sponsored terrorism that would continue and worsen under the subsequent military dictatorship, which came to power after a 1976 coup and justified its government takeover largely as a response to the chaos of the years in which el Brujo reigned as the Peróns’ closest adviser.

Figure 1: José López Rega, Argentine Minister of Social Welfare (1973–1974), 24 September 1974, Wikimedia Commons

To this day, references to el Brujo—be they biographical, journalistic, political, cultural, or literary—often mention his sinister political power, this period of terror, and his dalliances with the occult in the same breath. He appears as a character in several literary works, most notably Luisa Valenzuela’s Cola de lagartija, in which he is depicted as megalomaniacal, hermaphroditic monster working dark magics to gain power. López Rega’s beliefs in the spiritual realm, and in his own ability to control it, are intimately linked with his actual rise to political power in the Argentine cultural imagination.

My research revolves precisely around these associations with unseen, sinister forces that are often highlighted in literature, film, and cultural discourses related to the Southern Cone dictatorships. López Rega is a fascinating figure for this reason: although the AAA operated under the democratic government that preceded the 1976 coup, thus prefiguring the much larger scale detention, disappearance, and murder of 30,000 people under the military government from 1976–1983, he is often remembered and represented with a notable level of mystery, superstition, and fear. One archivist that I worked with during a research trip to Argentina noted amusedly that the lights in her building had even briefly gone out when she went to fetch a copy of López Rega’s 758-page spiritual magnum opus, Astrología esotérica, for me to peruse—a strange omen.

On one level, an interest in López Rega’s biography and uncommon beliefs form part of a search for an explanation for his unexpected rise to power. A relatively uneducated, working class man, who was completely uninvolved with politics before the mid-1960s, it seems somewhat unfathomable that he should reach such a position of power and influence between 1965, when he met Isabel Perón, and 1973, when he was named Minister of Social Welfare. Faced with this trajectory, historians and journalists have examined el Brujo’s published texts and stories of his behavior seeking to shed light on his biography and personality. For example, sections of Astrología esotérica were reprinted, with commentary, in a July 1975 pamphlet as a “type of mental history, of intellectual identification of its author” that would “constitute a small contribution toward better analyzing the current moment in Argentine politics.” The pamphlet advised “that the reader come to his own conclusions,” but notably included quotations from more renowned astrologers who reviewed the book and declared him a charlatan, inept in the methods of “rational astrology.”

Like the compiler of this pamphlet, some writers have implied or openly concluded that López Rega’s behavior and professed beliefs were all part of an elaborate performance meant to manipulate and impress those around him, particularly Isabel Perón. Isabelita, who, as her husband’s vice president, would become president after his death in 1974, is repeatedly portrayed as having been impressionable and, as the adopted daughter of Spiritists and purportedly a believer herself, particularly susceptible to this type of performance.3 Others have treated them as the genuine, though absurd, illusions of an irrational narcissist. Whether they view him as a calculated manipulator or un loco, many writers, impressed by the terrible impact of el Brujo’s actions, tend to portray López Rega as a sinister force impacting the era’s political landscape.

On another level, an emphasis on linking López Rega and Peronism more generally to esoteric practices might very well have been a discursive strategy employed by the military government after the 1976 coup, which was explicitly and even aggressively Catholic, to further justify its takeover and position itself as a break with the earlier chaotic government. In July of 1975, López Rega was forced to resign from his position and fled Argentina in the face of accusations linking him to the AAA, among other crimes. In March of 1976, the Armed Forces deposed Isabel Perón, installed a junta in her place, and carried on the repressive activities of the AAA with the full force of the state and organization of the military. López Rega would remain in hiding until 1986, but his crimes and his spiritual beliefs would periodically return to the public eye. In May 1979, for instance, some of his belongings were seized by the federal police from a residence where they had been kept and exhibited to the press: stories in major newspapers and magazines highlighted texts on masonry and astrology, various rings, capes, and stoles, and a mysterious doll resembling either Juan Perón or López Rega that articles speculated may have been used in occult rituals.4

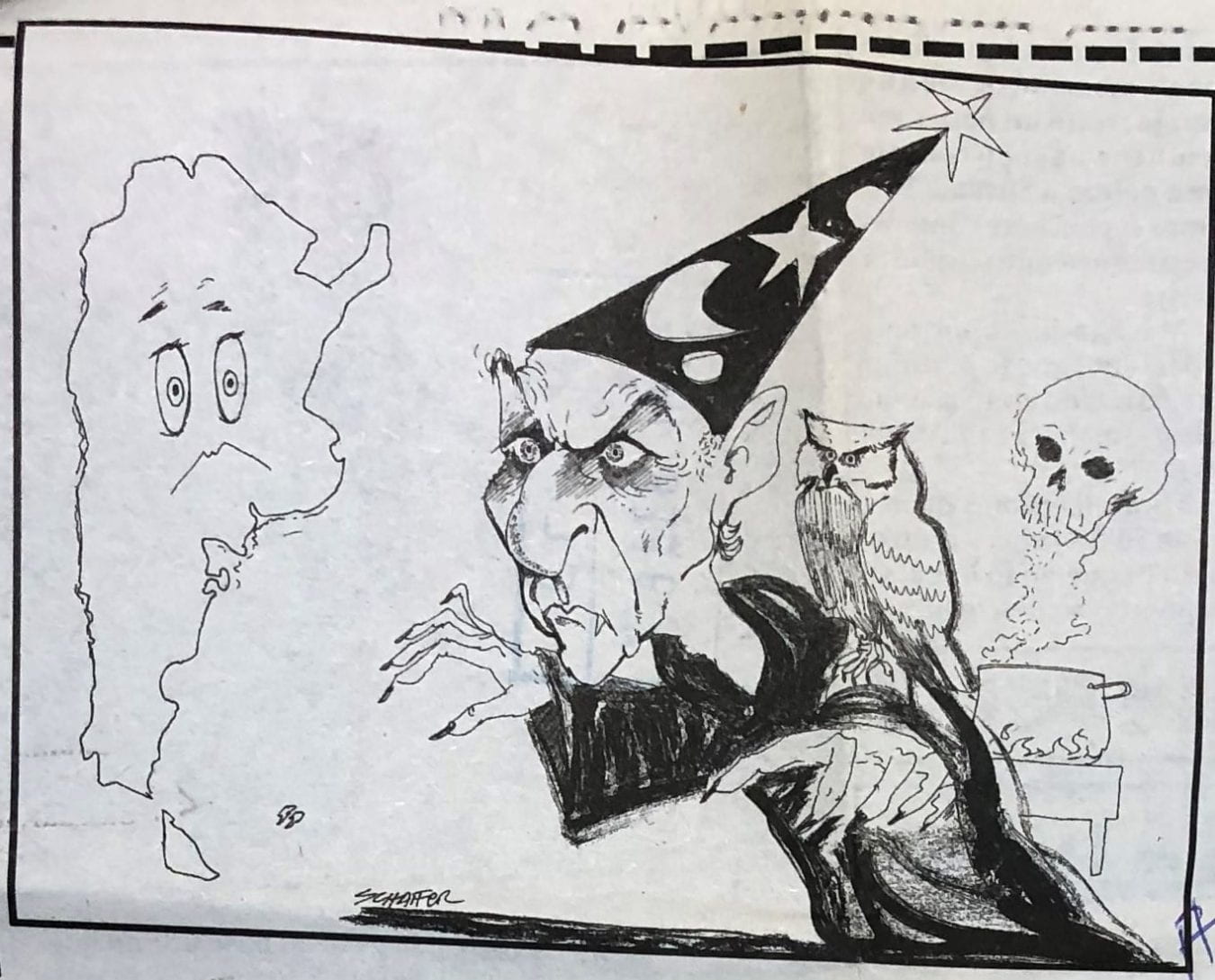

Figure 2: A cartoon depicting el Brujo López Rega, published in Flash, February 29, 1996. López Rega, José, Fondo Editorial Sarmiento, Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno.

Finally, cultural interest in José López Rega may indicate the way that sinister, otherworldly conspiracies and esotericism are felt to reflect the lack of transparency of power under political conditions at the time. One writer has argued that López Rega’s behavior was reflective of Perónism itself, a political movement that often “resolved itself in privacy, traversed by esotericism.”5 In every dictatorship of the Southern Cone, and even under Argentina’s democratic government in advance of the coup that brought the military governments to power, political events were unduly determined by unaccountable groups of oligarchs and military men, not to mention US intervention. The AAA and the Argentine military government’s kidnappings and murders of alleged subversives were open secrets, conducted in broad daylight and in plain view of witnesses, but responsibility was repeatedly denied by those in charge. The power wielded by the authoritarian regimes depended upon this ability for paramilitary groups and secret services to instill fear and uncertainty in citizens and thus control their movements and limit dissent, even as the regimes themselves claimed plausible deniability or blamed their own actions on guerrilla opposition forces. In the face of this level of terror, confusion, and outright gaslighting of the population, it is not hard to believe that sinister forces are at work—whether they are wholly human or somewhere beyond.

1 Pressly, Linda. “The 20-Year Odyssey of Eva Perón’s Body.” BBC News, BBC, 26 July 2012, www.bbc.com/news/magazine-18616380.

2 Larraquy, Marcelo. López Rega: La biografía. Sudamericana, 2004, p. 175.

3 See for example “Cantor, policía, ministro, hoy requerido.” El Mundo [Uruguay], Nov. 4 1976. López Rega, José, Biografía, Fondo Editorial Sarmiento, Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno; Vicens, Luis. El Loperreguismo. El Cid Editor, 1983; and Feinmann, José Pablo. López Rega, la cara oscura de Perón: Apuntes sobre las Fuerzas Armadas, Ezeiza y la teoría de los dos demonios. Editorial Legasa, 1987.

4 See La Crónica, May 3, 1979; La Nación, May 2, 1979; La Nación, May 3, 1979; La Prensa, May 3, 1979; Clarín, May 3, 1979; Diario Popular, May 3, 1979. López Rega, José, Curanderismo, Fondo Editorial Sarmiento, Biblioteca Nacional Mariano Moreno.

5 Feinmann, p. 70.