Jan 31, 2020 |

Frida Plata, Student, MA Program in the Humanities (MAPH)

In order to study Mesoamerican art, we must frequently ask ourselves an important question – what elements can we derive from the objects themselves, and what are we deriving from our imagination to fill in the gaps of knowledge? The buildings and art of Chichén Itzá can help us consider how the imagination fills knowledge gaps, especially for a discipline like Mesoamerican art history that requires a substantial amount of information derived from the object itself. Close looking of the objects at Chichén Itzá helps us to reconsider posited theories about the site’s art and architecture, especially because of the limited primary sources available to us about Chichén Itzá. Much of the site’s documentation was destroyed by Diego de Landa (a Spanish Bishop who proselytized to the locals and helped colonize the region) upon his arrival during the sixteenth century. So, the codices that would have helped us decipher Mayan script have left us with many unanswered questions about the history, architecture, and art of Chichén Itzá [1]. Still, despite our limited primary sources, Chichén Itzá’s remains provide the visual information that can allow us to decipher the site’s meaning and aesthetic contributions to Mesoamerican art. In the fall of 2019, the Art History department offered a traveling seminar, led by Associate Professor Claudia Brittenham, to conduct the close looking necessary to reconsider methodological approaches taken thus far toward investigating Chichén Itzá and Mesoamerican art.

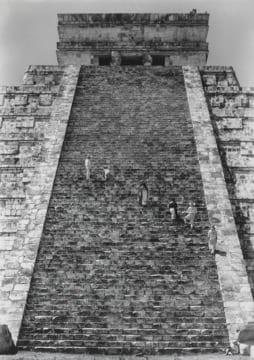

One different methodological approach when examining Chichén Itzá’s material evidence includes re-visualizing the site through the eyes of other artists. One artist in particular, American photographer Laura Gilpin, captured images of Chichén Itzá that allow us to see the complex designs of the site’s art and architecture. In 1932, Gilpin captured the first important documented photograph of the Castillo before sunset during the equinox [2] (Fig. 1). The north side of the Castillo depicts a serpent made from light and shadow that appears to slither down the pyramid’s west balustrade. This sophisticated projection of the great “Plumed Serpent,” an important supernatural figure in Mesoamerica, just begins to demonstrate Chichén Itzá’s sophisticated and fascinating architecture.

Figure 1. Laura Gilpin, Steps of the Castillo, Chichen Itza, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 35.4 x 26.7 cm

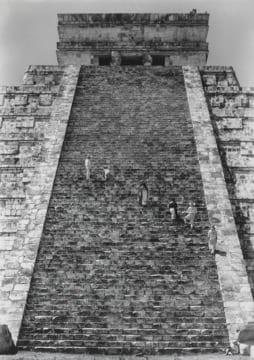

Another one of Gilpin’s significant images of the Castillo is Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan (1932) (Fig. 2). The photograph depicts six people scaling one of the Castillo’s stairways at Chichén Itzá. Even though the Castillo technically has four stairways, Gilpin features only one of the stairways in her photograph, thus simplifying the use of the space and eliminating any other possible processional pathways leading to the temple that sits on the ninth (and last) platform at the top of the building. From the top of the building to the bottom of the stairway, Gilpin photographs the Castillo from a centralized low angle, making the stairs seem gargantuan and thus seeming to create a monument of the Castillo while also adding a sense of drama to the long and steep trek to building’s entrance. Despite the elaborate, open-mouthed serpent heads on either side of the stairway entrance, Gilpin crops out most of the serpent heads from the photograph, emphasizing the stairway in the photograph more than any other architectural or ornamental feature of the Castillo.

Figure 2. Laura Gilpin, Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan, 1932. Gelatin silver print, 34.5 x 24.3 cm

As one moves their eyes towards the top of the Castillo’s stairs, they notice the temple’s entrance, awaiting the people scaling the stairs to enter it. The temple’s entrance appears perfectly aligned with the stairway, emphasizing a centrality and symmetry in the photograph. Symmetry and centrality are further emphasized by the design of the temple itself—two rounded columns evenly divide the temple’s entryway and help to unify the symmetry of the photograph.

One can also note the symmetry in Stairway of the Temple of Kukulcan by the linear repetition throughout the photograph. For example, the repeated horizontal pattern of the stairs helps to emphasize the symmetry of the photograph as the pattern takes up the center of the page. In addition to the repeated horizontal linear patterns in the photograph, the vertical lines that comprise the balustrades also play an important role within the photograph. The vertical lines in the image not only frame the symmetry of the repeated pattern of the stairs, but these vertical lines contribute to the monumentality within the photograph. They provide a sense of stability and strength to the image, much like the rounded columns at the temple’s entrance also provide a sense of stability, strength, and monumentality to the photograph. With the way that Gilpin utilizes line repetition to frame the stairway that leads to the temple, in addition to the people scaling the stairs that look toward the temple’s entrance, we are compelled to consider what resides beyond the temple’s doorway. Though one can visibly see the doorway’s entrance at the top of the stairs (as this photograph was captured during the day), they cannot see within the building because it is concealed in complete darkness. Still, even though we cannot see inside the building, we cannot help but wonder how the Maya utilized the space within and what they conceived when they were constructing the Castillo.

Regarding the people photographed in this image, they all wear seemingly traditional Maya dress. The women in the image appear to wear huipiles, the traditional white and embroidered dress of Maya women, their skirt hems decorated with detailed embroidery [3]. The men wear huaraches and straw sombreros (though short pants and tunics are more common), providing some shade against the strong Yucatec sun as they scale the Castillo’s steep stairway. As these people scale the stairs, their bodies create a diagonal line across the stairway, breaking the centrality and symmetry of the photograph. The young boy sitting and leaning against one of the serpent heads at the end of the balustrade at the bottom of the stairway also functions within the image in a similar manner, breaking the symmetry in the photograph as he sits alone, observing the others scale the Castillo’s stairs. In addition to breaking the centrality and symmetry within the photograph, the diagonal line created by the people in the photograph gives the image a sense of action and dynamism, which contrasts the stability provided by the horizontal linear repetition of the stairs and the vertical repetition of the balustrades.

Upon actually seeing the Castillo during the traveling seminar, we realized just how the ancient Maya strategically employed certain optical illusions to emphasize the pyramid’s monumentality. For example, the area surrounding the Castillo remains empty, thus making the Castillo appear much larger than the other buildings distantly placed from the pyramid. In addition, the Castillo itself incorporates an optical illusion of sorts in its design. As one moves their eyes form the bottom to the top of the pyramid, they can observe that the squares on each platform incrementally decrease in size toward the top, thus making it seem as if the Castillo is much larger than its somewhat modest size, especially compared to other pyramids in Mesoamerica (such as Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Moon and the Great Pyramid of Cholula in Puebla). Naturally, actually being able to visit Chichén Itzá through this traveling seminar opened up many more questions about this fascinating site. It will certainly continue to perplex and fascinate art historians as we continue to investigate and uncover its meanings.

Footnotes:

[1] Linnea Holmer, et al., Lanscapes of the Itza: Archaeology and Art History at Chichen Itza and Neighboring Sites (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018), 37.

[2] John B. Carlson, “Pilgrimage and the Equinox ‘Serpent of Light and Shadow’ Phenomenon at the Castillo, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán,” Archaeoastronomy: The Journal of Astronomy in Culture 14, no. 1 (1999): 138.

[3] Phillip Hofstetter, Maya Yucatán: An Artist’s Journey (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2009), 107.

Jan 9, 2019 |

Jack Mensik, MA Student, LACS

“This is the water!” Elena exclaimed. She scurried back to the living room from the kitchen and excitedly set the glass down on the table in front of me.

“Wow, it looks pretty clean,” I responded. I was not exaggerating. Specks of distant sunlight shimmered in the translucent water, whose unblemished appearance belied the fact that it had been collected from rainfall in a city notorious for its air pollution. For the past few years, Elena and her husband, Antonio, have relied on a household rainwater harvesting system to meet a substantial portion of their family’s water needs. Isla Urbana, an organization dedicated to the proliferation of rainwater harvesting in Mexico City, designed and installed this system, which captures water from Elena and Antonio’s roof, passes it through a series of filters, and stores it in a 5000-liter plastic cistern in their backyard. In their kitchen, another set of filters purifies the water to a quality suitable for drinking. They’ve done tests, Elena told me, and the quality is consistently excellent.

Figure 1. A household rainwater harvesting system that serves as an important source of clean water for residents of Mexico City’s periphery.

In truth, the clean water contained in the glass offers Elena and Antonio more than just good health. It affords them the possibility for a stable livelihood amidst circumstances in which they enjoy only marginal access to the rights and privileges promised to citizens of North America’s largest city. Reliance on the rain has meant that the family is no longer at the mercy of a government that is unsure of whether their household is deserving of piped water service. Yet, as Elena beamed with pride over the immaculate glass, I also wondered whether this newfound stability would make their otherwise rightless status more tolerable. After all, why would the family bother to seek legal recognition from government authorities if a public service like water was no longer urgently needed?

Elena and Antonio’s lack of formal land tenure explains how they discovered rainwater harvesting, and why they are so enthusiastic about it. The family’s home sits in a rolling mountain valley on the southern periphery of Mexico City within the city’s “ecological zone”, a conservation area in which human habitation is prohibited. Elena, Antonio, and their young children settled the unoccupied piece of land without legal sanction in the early 2010s. The growing family had become too big for their small house in San Gregorio Atlapulco, an urbanized area located a few miles away in the borough of Xochimilco. They had to build a home from scratch on the mountainside, but they found relief from the cramped conditions in which they had been living. Yet, because they had illegally occupied their land, they were ineligible for almost all government services. Elena and Antonio felt the absence of piped water most acutely. They narrowly missed an opportunity to enroll in a municipal program that would have offered them a monthly delivery from water trucks (locally known as pipas) at a subsidized cost. Meanwhile, the full cost of a monthly pipa delivery was more than they could afford on a regular basis. So, they would make trips down to a pump in San Gregorio, fill up a half-dozen or so 19-liter jugs with water, and either hire a taxi to bring them home or haul the jugs back uphill themselves in a cart. It was tiresome work, but unless the city government redesignated their community’s land tenure status as part of the “urban zone”, rather than the “ecological zone”, avenues for improvement remained limited.

Figure 2. An example of a pipa, or water tanker truck, that delivers water to many of Mexico City’s residents.

Elena and Antonio’s decision to seek a better life on Mexico City’s geographic and legal periphery repeats a logic that has been commonplace in the city for nearly a century. Since the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1917, inner-city residents have looked to the city’s periphery as a place where single-family home ownership could be realized, far from predatory landlords, burdensome rents, and squalid living conditions. Meanwhile, since the end of the Second World War, informal settlements on the periphery have also absorbed influxes of rural migrants seeking economic opportunities in the national capital. Over time, many informal communities have received legal recognition from the state, and have been integrated into the city through the extension of public services. These patterns of migration, settlement, and eventual legalization have played a key role in the Mexico City’s rapid expansion from a contained city of 369,000 in 1900 to a sprawling megalopolis of over 20 million today.[1]

Yet, city and municipal governments are often hesitant to recognize informal settlements. In decades past, officials marshaled concerns about sanitation as a justification. Today, environmental considerations, specifically those surrounding water, occupy a central role in government discourse. The vast majority of the “ecological zone” occupies territory in the southern portion of Mexico City comprised of rural towns, farms, and mountain forest. The area’s vegetation plays a vital role in absorbing rainfall and recharging the subterranean aquifer upon which the metropolis depends for its water supply. Authorities are concerned that unrestricted settlement will lead to urban sprawl and loss of this important green space. [2] These apprehensions are justified, as the future of Mexico City’s water supply looks bleak. Decades of intensive extraction to quench the city’s thirst, coupled with miles of paved surfaces that prevent replenishment, have severely diminished water levels in the aquifer. In fact, this drop has caused parts of Mexico City to physically subside—the sight of uneven streets or buildings tilted at alarming angles are fairly common. Aqueducts that supplement the city with water from neighboring states are inefficient and costly.[3] Indeed, Mexico City is running out of water, and years of unsustainable growth have threatened the city’s survival.

Figure 3. The “ecological zone” found prominently in southern Mexico City in which vegetation plays a vital role in absorbing rainfall and recharging the subterranean aquifer.

However, the city’s vigilance over the aquifer also means that residents living in hundreds of informal settlements within the “ecological zone” are unlikely to receive the adjusted land tenure that will be necessary for basic improvements in water services and infrastructure. “It puts us in a dilemma,” one municipal official told me, “because on one hand, [water] is a right that everyone has. But by beginning to recognize these irregular communities, then what becomes of the conservation of natural land? Yes, [water] is a right, we cannot deny it. But also, there are certain limits that we cannot exceed through our actions.”[4]

Isla Urbana’s rainwater harvesting systems offer one solution to this dilemma, as the contraptions can expand water access without placing additional stress on the aquifer. “Rainwater harvesting gives you a tool that you can select exactly the houses or neighborhoods that are most problematic, or for any reason the city has failed to supply adequately,” explained the organization’s founder, Enrique Lomnitz. If these water stressed areas are supplemented with rainwater, he reasoned, it would reduce the burden on Mexico City’s water supply and infrastructure.[5]

Most of Isla Urbana’s work consists of government-sponsored programs, in which they install rainwater harvesting systems in formally recognized communities where water infrastructure performs poorly. Yet, through private donations, Isla Urbana is also able to service informal communities, many of which are in the “ecological zone.”[6] After connecting with Isla Urbana through mutual acquaintances, Elena and Antonio rounded up enough interested neighbors to begin a project of their own. The couple had to pay 3050 pesos (about $150 US dollars) to cover part of the cost of their own system, but they began harvesting rain shortly after its installation.

So far, Elena and Antonio are thrilled with the results. During Mexico City’s rainy season, roughly between June and October, powerful rains fill their cistern up with water that lasts into the dry season, meaning they save money they spent on pipas and time they spent on trips to the water pump. In the coming years, the couple hopes to expand their storage capacity so that their supply will last even longer. “To this day, we don’t suffer from water,” Antonio declared, “The system is very good and it has helped us a lot.”[7]

While rainwater harvesting has brought greater stability and comfort, the couple still expressed a desire for legal land tenure and improved infrastructure. They would like to see some form of piped water service, or at least more pipa trucks. “We all have rights to these things,” Elena argued, “Just as we have a right to light, we have a right to water. We have rights to urban services. And just because we live up here doesn’t mean we have no rights. We have the same rights as those who live down [in the city].”[8]

I sensed a gap, however, between Elena and Antonio’s belief that they had these rights and their ability to live without them. Previously, I had spoken with numerous residents of formally recognized communities, most of whom saw rainwater harvesting as more of a temporary fix that could never truly substitute for efficient piped water service. Elena and Antonio, on the other hand, seemed committed to rainwater harvesting for the long-term and relatively unfazed by the improbability of infrastructural improvement in their community. When I asked them why, they stated that they were concerned about the dwindling aquifer, and felt that rainwater harvesting and water conservation were essential steps for a better future. Even if their land tenure changed and services arrived, they said, they would continue to harvest rainwater. “We have [rainwater harvesting], it has helped us a ton,” Elena explained, “But yes, if piped water came, then that too. But also…as we said before we have to be conscious, right? Although we have piped water, save it, right? Take care of it.”[9]

Residents of other informal settlements echoed Elena and Antonio’s enthusiasm for rainwater harvesting, as well as their ambivalence toward legal land tenure and improved service. “I am doing very well with rainwater harvesting. I’d neither ask nor demand much else,” one woman told me, “If they come to tell us, ‘Guess what? They’re going to install pipes,’ I’d say, ‘Well, That’s fine. That’s good, isn’t it?’ But if not, then no. Because…with the rainwater harvesting system, well, the truth is that I’m fine.”[10]

Others expressed a similar dedication to rainwater harvesting on account of environmental concerns. “Sure, I would like to see it regularized,” one man said, “but I will keep collecting rainwater. Yes, I would keep doing it. Why? Because this way I am helping out the environment a bit, I’d say. Because sometimes you talk and you don’t do much…”[11]

These comments reveal the extent to which Mexico City’s water crisis is not simply an environmental issue, but cuts to the core of the city’s longstanding struggle with social inequality. Rainwater harvesting appears to do an excellent job of meeting informal residents’ water needs, and provides them with a greater sense of security that they can remain in their homes for the immediate future. Yet, the systems do not resolve critical legal issues surrounding land tenure in informal settlements that would establish permanent residence. Residents’ ambivalence toward resolving these issues may simply reflect doubt that their day of recognition will ever come. Their passion for rainwater harvesting is inspiring, but laden with resignation toward a tolerable, but rightless, livelihood on the periphery.

Both authorities and residents of Mexico City care deeply about their city’s environmental future. However, reaching a sustainable solution to an increasingly dire water crisis will require reckoning with difficult questions about what it means to be a full citizen of Mexico City and who can acquire this status. Until then, every raindrop that falls in the Valley of Mexico will be worth saving.

[1] Matthew Vitz, City on a Lake: Urban Political Ecology and the Growth of Mexico City (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 4, 89-92; Thomas Benjamin, “Rebuilding the Nation,” in The Oxford History of Mexico, ed. William H. Beezley and Michael C. Meyer (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 470; Wayne Cornelius, Politics and the Migrant Poor in Mexico City (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1975), 16-17, 27-28.

[2] Jill Wigle, “The ‘Graying’ of ‘Green’ Zones: Spatial Governance and Irregular Settlement in Xochimilco, Mexico City: Irregular Settlement in Xochimilco, Mexico City,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38, no. 2 (March 2014): 573–89, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12019.

[3] Barkin, David. 2004. “Mexico City’s Water Crisis.” NACLA Report on the Americas 38, no. 1: 24-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2004.11722401; Connolly, Patricia. 1999. “Mexico City: Our Common Future?” Environment and Urbanization 11, no. 1 (April): 53-78. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789901100116; Kahn, Carrie. “Mexico City Goes Days Without Water During Maintenance Shutdown.” NPR.Org. Accessed November 10, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/10/31/662786981/mexico-city-goes-days-without-water-during-maintenance-shutdown.

[4] Interview, August 27, 2018.

[5] Interview, August 14, 2018.

[6] Interview, August 14, 2018.

[7] Interview, August 24, 2018.

[8] Interview, August 24, 2018.

[9] Interview, August 24, 2018.

[10] Interview, August 22, 2018.

[11] Interview, August 15, 2018.

May 18, 2018 |

Ámber Miranzo, LACS MA’18 / Communication at CLAS

EntreVistas, chats about Latin American politics, culture and history’ is the new series of podcasts of the Center for Latin American Studies, where once a month we sit with professors to talk about some of the most exciting topics they research. Decolonization, police reform, Latin American citizenship, and patronage relations in Bolivia are some of the topics coming up in the next issues.

You can subscribe to the series in iTunes, Stitcher or Google Play.

* * *

Episode 1. May 2018.

What do we do with monuments? What do they represent? In this first interview, we talk with Miguel Caballero Vazquez about how these issues were addressed in Brazil, Mexico and Spain in the mid-20th century. In this period, political regimes thought of monuments not as artifacts to merely commemorate the past, but as tools to change who they are.

Image 1: Map of the pilot plan of Brasília, designed by Lúcio Costa, 1956. Image 2: Torre Latinoamericana, Mexico City. Image 3: Protective armor of the Cibeles Fountain

during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

How is that change performed? The city of Brasília constitutes a case where a whole city was conceived as an intimate monument, a monument to live in. Miguel Caballero discusses with us the ideals behind Lúcio Costa’s plan of 1956 and some of the controversies they generated.

We move on to Mexico to comment on the meaning of Latin American skyscrapers. Are they symbols of US capitalist ideology? Do they represent something else? Architect José Mújica, in Post-Revolutionary Mexico has a perspective on how skyscrapers are both modern and a salvage of the pre-Columbian past.

Last, the case of Madrid during the 2nd Republic (1931-1936) and the Civil War (1936-1939) sparks questions about what happens when the meaning of existing monuments change. When the Republic arrived, there was a discussion about what cities look like, and how cities represented oppressive regimes from the past. What do you protect and what do you destroy? Miguel Caballero comments on the contending perspectives in this period, as well as some of the actions the government followed.

Miguel Caballero Vázquez, Collegiate Assistant Professor of Humanities at the University of Chicago, is currently completing a book manuscript titled Monumental Anxieties, on the controversy of monumentality and the reinvention of monuments between the 1920s and 1970s.

Mar 7, 2016 |

María A. Gutiérrez Bascón, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures

It was on a rainy afternoon in Havana, in the summer of 2012, that I set out to visit a rather intriguing object that several people had mentioned to me. La Maqueta de La Habana was one of the largest scale models of a city in the entire world, if not the largest!, I had been told. But where was this seemingly impressive rendition of a Havana in miniature? Nobody had been able to tell me the exact location, besides the fact that the city replica was somewhere in the neighborhood of Miramar, between 1st and 3rd Avenue. I carefully looked through my comprehensive visitor’s guide of Havana in search of more information, but there was no mention to this huge scale model. The only maqueta referenced was the relatively small one located in one of the touristy streets in Old Havana.

As interested as I am in the ways in which the city of Havana has been imagined and portrayed by writers, filmmakers, visual artists, architects, and urban planners after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I knew I had to visit the Maqueta de La Habana before leaving the island. My time in Cuba was coming to an end, so I decided to embark on a trip from my apartment in Old Havana to Miramar. Crossing Havana in the rain can become quite a task sometimes, as I was reminded that afternoon. Bus delays and a pouring rain that often flooded certain parts of the city put me in the neighborhood of Miramar at a later time than I had planned, but I still thought I had made it on time. I seemed to be on the right street, but I couldn’t find the maqueta. After asking at the nearby bar, I was given more concrete directions. When I finally found the building, I saw that the doors were closed. Very, very closed, as if they hadn’t been opened in quite some time. “They’re probably closed today because of the rain,” the friend that came with me that afternoon told me. “Well, I guess I’ll never know,” I said. I was leaving Havana the next day!

Fortunately, I was lucky to go back to Havana the following summer. The very gracious Gina Rey, Havana-based architect, received me in her house that summer. I had met her the year before, but I wasn’t aware that she had been one of the creators of La Maqueta de La Habana in the late 1980s. Architect Rey told me that the scale model was indeed closed to the public, and had been for some time, because the pavilion that hosts the maqueta was in an advanced state of disrepair. “There are some problems in the ceiling, and they don’t want anybody to get hurt,” she said, “so they don’t let tourists in anymore.” A quick Internet search about the maqueta retrieved a comment from a Canadian tourist who had been able to visit the small-scale Havana before it was indefinitely closed to the public: “I was told that it is ‘under renovation’ because a tourist had an accident there last year.” It is not without irony that this idealized depiction of Havana—as all scale models are, in their abstract, almost utopian character—was being threatened by the ruinous pavilion that hosts it. The ideal city could perish under the ruin of a crumbling ceiling.

This contradiction between the ideal character of a Havana in miniature and the rubble that the pavilion could potentially turn it into made the maqueta all the more captivating. Architect Gina Rey was very kind in arranging a visit for me. She would call the security guard and tell him to let me in the pavilion so that I could take pictures of the model. When I got there the next day, I noticed that the enormous panels of the maqueta had been disassembled. As if the scale model was acquiring part of the ruinous condition belonging to the ceiling above it, its panels stood a few inches apart from each other. It was a striking view —the city in miniature looked fractured, as if it had been affected by some unexpected catastrophe. It was a huge scale model indeed, as I had been told. Approximately 144 square meters (472 square feet) in size, the model took 18 years to build, according to one of the brochures left on a table at the maqueta pavilion. According to Cuban writer Antonio José Ponte, who has reflected upon this small-scale Havana in several of his texts, the maqueta would be the second largest of its kind in the world, only surpassed by “The Panorama City of New York.” In addition to its size, the color code of the maqueta is probably one of its most salient aspects. Each building is colored according to the time when it was built. Constructions built in the colonial period appear in terracotta, while buildings from the republican era are painted in ochre and edifications planned by the Revolution are beige. Interestingly enough, both cemeteries and projects that have not yet been built are painted in white. Antonio José Ponte has noted that there’s some irony in the fact that both the past— those who have passed—and what is yet to be born share the same color in the scale model (1). Does this somehow point to the relative constructive paralysis that affected the period after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, linking revolutionary architecture in Havana to stagnation, or to death? In fact, as the maqueta shows, Havana has a lot of ochre—buildings from the pre-revolutionary period—and not so much beige (revolutionary architecture) in it.

This relative constructive inactivity during the revolutionary period has been the perfect backdrop for numerous depictions of Havana as a city frozen in time, particularly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Not having suffered any major renovations in a few decades, the Cuban capital seemed like the perfect projection screen for those affected by a feeling of nostalgia for a time when certain utopian projects were still thought possible. Various glossy photographic albums that portrayed Havana as a crumbling city stuck in time started to circulate widely in the early 1990s, with the onset of the so-called Special Period on the island. And however cliché the image of a Havana suspended on the verge of collapse might be, there is a certain truth to the claims of disrepair that many have raised when referring to the Cuban capital during the last twenty years. Even by conservative governmental accounts, more than 52% of the buildings in the country—not only in Havana—are facing decay (2). To address these issues, the Office of the Historian of Havana put in place a plan to restore the old city. While successful in recovering and protecting a number of buildings of great architectural value, the scope of the plan has been limited to the intramural city. The rest of the city is left to fend for itself, facing serious problems such as poor housing, overcrowding, and deteriorated infrastructure.

After having crossed the crumbling Centro Habana to get to Miramar and see the scale model, I reflected upon these questions surrounding nostalgia, ruins, and utopia. As I gazed over the maqueta, I asked myself how a miniature of Havana—this miniature, or any miniature, for that matter—could capture the ruins of a city. In fact, the catalog of the scale model claims that the replica has an absolute faithfulness to the real city. But how can that fidelity even be possible, with the frequent collapses of buildings in Centro Habana after each storm that hits the city? Does a wooden block from the maqueta disappear every time a building partially or completely falls to the ground in the real city?

Interestingly enough, I thought, this Havana in miniature wasn’t shaped with the usual materials of which scale models are made. Built during the Special Period, the maqueta had to be made of a more affordable and readily available material at the time: the discarded wooden boxes of Cuban cigars. If we consider the place that tobacco holds in well-known imaginings of the Cuban nation—which have one of its most important articulations in Fernando Ortiz’s essay Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar (1940)—, it’s not hard to see the maqueta as being made, in a quite hopeful gesture, out of the rubbles of the nation.

Perfect in their straight lines, the maqueta blocks made of discarded tobacco boxes seem to point to the (im)possibilities of making utopian gestures towards the (re)construction of a city that holds a significant place in our political dreams and nightmares. How do we imagine and cope with the ruins—not only the ruins of Havana, but of the great utopian projects of the twentieth century, for which the Cuban capital is an important signifier? Ponte has criticized the scale model of Havana for its inability to account for a crumbling city. I would argue, however, that the maqueta does capture the ruin, but in a less obvious way. Within the utopian impulse that any scale model presupposes, there is always a fracture. In the maqueta, the rubble makes its way through the discarded tobacco boxes, as to quietly remind us, perhaps, that utopia is not without its ruins. And that ruins, possibly, may themselves be the material from which to build our new utopias.

Footnotes

(1) Ponte, Antonio José. “Carta de La Habana. La maqueta de la ciudad.” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, 649-659 (2004): 251-255.

(2) Data quoted by Ponte in “La Habana está por inventarse.” El País 21 Jan. 2006.

Please note:

The contents of this blog do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Latin American Studies or the University of Chicago.