Nov 13, 2020 |

Ana Beraldo, PhD, Sociology, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Brazil/ Former Visiting Student, CLAS (2018–19)

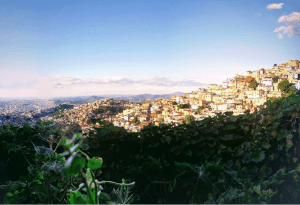

Figure 1. Morro da Luz, picture taken by the author, April 2019

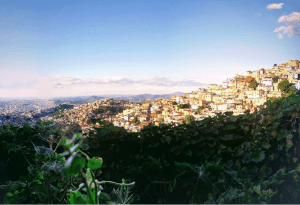

Figure 1. Morro da Luz, picture taken by the author, April 2019

A Fortress of Crime

“We live in a fortress of crime,” said Thiago (pseudonym) as he tried to explain to me how daily life works for those who live in favelas. He is a 23-year-old black man who I met while conducting my doctoral ethnographic fieldwork at Morro da Luz (fictitious name), a large shantytown in the city of Belo Horizonte[i], Brazil. I myself grew up in the same city, in a middle-class neighborhood not far away from Morro da Luz, and yet I noticed that Thiago was making an effort to translate so that I could really grasp the reality he was portraying, at the same time so close and so distant from my own.

When Thiago described the favela as a “fortress of crime,” he was talking about how criminal groups, especially the ones involved in drug trafficking, create order in the territory by establishing moral parameters of rightness and fairness. Through actions such as punishing those that rob inside the community, killing socially recognized rapists, quickly taking sick people to the hospital, or making sure public service workers are well treated while performing duties that are important for neighborhood residents, criminals exert a governance that goes far beyond the limits of the criminal groups themselves and that regulates behaviors and relations in the peripheries in a broader sense.

Since these groups are heavily armed, their actions are anchored in the possibility of the use of force, and, not infrequently, in the actual use of it. But that alone would not be enough to form an effective criminal governance. Not just at Morro da Luz but in many similar places around Brazil and Latin America, criminal organizations have managed to successfully build for themselves a level of legitimacy that, although far from being total or hegemonic, is definitely significant.

Often enough, the governance exercised by criminal groups offers some protection—albeit in problematic ways —to a population vulnerable to many types of violence, from police brutality to insufficient access to rights. While there is a socially shared image of “favelados” (favela dwellers) as potentially dangerous people from whom the rest of society should be sheltered, and while this representation is deeply connected to security policies that are based on incarceration, persecution, and murder of this fraction of the population, criminal groups acting in those territories (whose members usually grew up in the same neighborhoods in which they now engage in illicit activities) are able to differentiate between the poor and act more accordingly to what is constructed as right. Thiago explains it once again: “Here there is no mugging, there is no rape, there is no this and that, but this is not because the police provides security for us, it is because the criminals don’t let it happen…we know that if it weren’t for them, things would be worse.”

A Battle against the Devil

As Thiago described those dynamics, he constantly emphasized that he does not approve of criminal activities nor does he agree with the violent ways in which criminal groups relate to each other, the police, and the community as a whole. As proof of that disagreement, he reminded me that he and his nine siblings grew up immersed in an evangelical environment, very much engaged with the activities of the church they attended on a daily basis— one among many scattered throughout the neighborhood.

Over the last five decades, Brazil has been experiencing important transformations, most strongly in the popular classes, both in regard to the religiosity of its people (with a reduction of Catholicism and a broadening of the evangelisms) and in regard to the dimensions and types of criminality and violence that characterize the country (with an expansion of illicit markets and an intensification of violent relations that are not exclusively, but considerably, related to those markets and to the ways they came to be structured in poor territories).

Interestingly, evangelical churches promote themselves precisely around the idea of a “battle against the devil,” and the devil, when it comes to places such as Morro da Luz, is profoundly linked to drug abuse and criminality. This has to do with Thiago’s argument that, since he was raised as a devoted evangelical, he could not agree with criminal activities. In Thiago’s claim, and in the discourses that circulate among poor Brazilian circles, crime and evangelism appear as rival sides of an everyday war for subjects and subjectivities. In that scenario, how can criminality and evangelism expand simultaneously in the same portion of the population?

Evangelisms in the Fortress of Crime

Figure 2. A pastor and an armed drug dealer talking, favela da Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Picture by Alan Lima, published October 19, 2017, available at https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/10/13/album/1507850793_088715.html#foto_gal_1.

Figure 2. A pastor and an armed drug dealer talking, favela da Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Picture by Alan Lima, published October 19, 2017, available at https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/10/13/album/1507850793_088715.html#foto_gal_1.

Through the ethnographic study I conducted in Morro da Luz, I identified that evangelisms and criminality are entangled, and that they connect with each other by two main phenomena: the conversion (from criminal, drug dealer, addict, to believer, evangelical, pastor)[ii] and the figure of the outlaw evangelical, increasingly common in the urban outskirts.[iii]

The converts experience a transformation of who they are, a construction of a new identity that is formed in opposition, but always attached, to the old one: they are and forever will be “ex-criminals,” “ex-traffickers,” “ex-addicts,” and so on. The converted bodies and presences in the favela seem to be signified as the living proof of the religious capacity of “salvation.”

At the same time, there are subjects that are “bandits” and “believers” who, while immersed in criminal networks, are also evangelical religious. In fact, for those who are inserted in illegal markets and in violent sociability, religious spaces can be one of the few places where they can take a break from the constant and tiring task of avoiding death[iv].

Both the convert and the criminal believer are usually very well received and integrated in evangelical temples and social relations. In my fieldwork in Morro da Luz, I realized that this is socially possible because the war the evangelisms are fighting is not between pastors and drug dealers, nor between religious and sinners, but between god and the devil. That is why Thiago could, at the same time, disapprove of criminality and recognize the criminals as a source of protection for the favela. The combat that goes on is otherworldly, transcendent. In the mundane sphere, they are all flawed humans, and, most importantly, they are all “favelados.”

[i] Belo Horizonte, a city with 2.5 million inhabitants, is located in the southeast of Brazil.

[ii] Also see: BRENNEMAN, R. “Wrestling the Devil: Conversion and Exist from Central American Gangs.” Latin American Research Review, v. 49, n. Special Issue, p. 112–128, 2014; and TEIXEIRA, C. A construção social do “ex-bandido.” [s.l.] Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2009.

[iii] See also: VITAL DA CUNHA, C. Oração de traficante: uma etnografia. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Garamond LTDA, 2015.

[iv] See also: RUBIN, J. W., SMILDE, D., JUNGE, B. “Lived Religion and Lived Citizenship in Latin America’s Zone of Crisis: Introduction.” Latin American Research Review, v. 49, n. Special Issue, p. 7–26, 2014.

Nov 30, 2017 |

Agnes Mondragon Celis Ochoa, PhD student, Anthropology

Photo by Toni François

Santa Muerte, a folk saint so little known before the turn of the century—in a religious landscape mostly populated by centuries-old figures—has become widely present in the Mexican public sphere in the past few years and, just as quickly, has been associated with criminality and drug violence in the media. This association has depicted Santa Muerte’s followers not only as criminals themselves, but also as engaging in illegitimate, even blasphemous, devotional practices. While this mass-mediated association resonates with old, Porfirian-age and ultimately colonial discourses linking Mexican lower classes to criminality —which of course, says more about class hierarchies in Mexican society than about Santa Muerte devotees themselves—I consider there to be, indeed, a relation between this saint and violence that remains unexplored. By examining a collective ritual that takes place in Santa Muerte’s main shrine in the downtown slum of Tepito, Mexico City, I wish to explore one of the ways in which such a relation plays out.

Tepito is a neighborhood best known for its massive informal market—where, allegedly, one can buy commodities of all imaginable kinds—but is also remarkable for its strong communal identity, which claims a pre-Hispanic past and which was able to resist gentrification efforts by the local government . It seems to have harshly felt the well-known effects of neoliberalism: unprecedented flows of money (especially of illegal trades), greater inequality, harsher capitalist competition, and the violence this brings about. The practices surrounding Santa Muerte, I argue, are means through which this violence is collectively acknowledged, evaluated and addressed, while offering a space by which the community of devotees reminds itself of such a fact and (ritually) reconstructs social bonds, which are crucial for both collective and individual survival.

Photo by Saúl Ruiz

On the first day of the month, devotees gather around the Santa Muerte shrine well before the main ceremony. Many are seen close to their Santa Muerte icons, either because they are holding them in their arms [image 1] or because they have placed them over a piece of cloth on the floor, like small, improvised shrines [image 2]. All sorts of small objects—candies, toy bills, beaded bracelets—can be seen in people’s hands or adorning their statuettes. The objects are gifts brought and distributed by devotees in return for miracles granted by Santa Muerte. As has become customary, devotees bring many such objects, which indicates the magnitude of the intended repayment. Devotees will offer them as gifts to several of the numerous Santa Muerte statuettes gathered on that day—insofar as all are equally indexes of the same Santa Muerte. While offering the saint her gratitude, however, it becomes unclear whether the recipient of the gift is Santa Muerte or (also) the devotee carrying the icon. Moreover, the gift is usually accompanied by a que te cuide y te proteja, “may she look after and protect you”, whose target is clearly a fellow devotee. In this way, the gift giver is demonstrating Santa Muerte’s efficacy to the recipient and encouraging others to engage in or maintain relations with her. As anthropologist Timothy Knowlton shows for a similar ritual, [5. Timothy Knowlton, “Inscribing the Miraculous Place: Writing and Ritual Communication in the Chapel of a Guatemalan Popular Saint”, Linguistic Anthropology, 25(3), December 2015] these individual communicative acts, superimposed on each other—as can be seen in the accumulation of gifts adorning the statuettes [image 1]—constitute and help sustain this collective devotion overtime.

But there is more to this. Gift giving, one of the classical concerns in anthropology, has been found to be at the very foundation of sociality, as acts that inaugurate (or, in our case, reestablish) social bonds and that carry the obligation to reciprocate. Following Nancy Munn, a gift may initiate a reciprocal transaction, and thus a social bond—a connection between the two persons involved where the gift giver is constituted and remembered as a generous person and her action reciprocated through a return gift sometime in the future.

This logic of reciprocity, although inverted, appears in devotional practices through which Santa Muerte followers attempt to harm others, to retaliate against others’ abuses of power or to counteract a competitor’s conspicuous economic success, situations that have become increasingly common, as mentioned, in recent years. The possibility to engage in these harmful practices, however, comes with a warning: Santa Muerte takes a loved one if a devotee fails to repay a favor. In other words, Santa Muerte takes revenge by mirroring the devotee’s harmful act, and thus breaking this devotee’s network of social bonds in the same way that she mirrors a devotee’s thankful repayment by creating a new social bond through gift giving, as the ritual above describes.

Knowledge about Santa Muerte’s revengefulness, for devotees, is thus a recurrent reminder about the perils of destroying social relations. Communal ritual practices not only result from the collective acknowledgment that a network of friends and kin is fundamental for everyday survival—especially in communities that have faced the hardships of poverty —but also that violence is ultimately unsustainable for social life. Santa Muerte followers then gather once a month in order to ritually suture back these severed bonds. In this way, the community becomes an agent that sustains itself into the future.

May 3, 2016 |

Erin McFee, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Comparative Human Development

Negotiators in Havana, Cuba ready their pens to sign a peace accord between the government of Colombia and the guerrilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which would end more than 50 years of war. More than 1,500 miles away, the Colombian department of Caquetá begins at the foot of the Western Andean mountains, where the jagged verdant peaks increasingly give way to rolling hills, vast expanses of cultivated land, and, eventually, dense Amazonian selva. Caquetá figures critically for post-conflict planners: it has suffered comparatively greater levels of violence and vulnerability than other areas of the country; it has a historically marginalized large rural population; it hosted part of the violently disastrous Zone of Distention between 1998–2002, in which the FARC took advantage of peace negotiations in order to regroup, terrorizing the civilian population in the process; and it will serve as one of seven Zones of Concentration for the eventual FARC demobilization.

Against the juxtaposed backdrop of dream-like landscapes and profound loss, a growing variety of community interventions attempt to make sense of suffering and contribute to sustainable peace over the long term. One such intervention includes a joint project between the Pastoral Social (community outreach team from the Catholic Church) and ACNUR (United Nations Refugee Agency), in which a team of five individuals—two psychologists, two anthropologists, and one lawyer—work with five communities displaced by conflict violence in Caquetá in order to realize collective reparations processes.

In early March, three members of the Pastoral Social set out to visit one of the participating communities: Roncesvalles.

Or was it Roncervalles?

Or Roncevalles?

No one is actually sure. Each person—including the community members themselves —remains more certain than the last that their spelling is, in fact, the correct one. The formal project proposal spells it with both the “r” and “s” throughout.

Orthographic concerns aside, Ronce/r/svalles comprises 55 families forcibly displaced by violence and relocated by the state to their current community, half of which floods in the event of heavy rains. The families did not know one another before they settled the partially soggy tract of land. This unfamiliarity, and the clear value differences between the two sections of the community, has resulted in significant tensions, which the project hopes to ameliorate through shared efforts to petition the state to repair the bridge leading to the community. This project was the order of the day for the Pastoral Social visit.

After half an hour on the main highway heading northeast out of Florencia (the department’s capital city, home to 140,000 persons), the branded ACNUR off-road vehicle turned into the entrance of Larandia military base. The army purchased the 3,375-hectare behemoth in 1965 in order to combat guerrilla threats in the region, and the massive training facility marked the beginning of the road to Ronce/r/svalles. In order to reach this community of many possible names, one must pass through the entirety of Larandia—including its three military checkpoints—enter the vehicle information in an Army registry, and return before six o’clock in the evening, when the checkpoint gates close for the day. Despite the official ACNUR vehicle status, branded with Agency logos and clear “No Weapons” decals, soldiers at each checkpoint questioned increasingly annoyed occupants as to their purpose, their number, and whether or not they were transporting weapons and/or hidden persons. Upon exiting the base, the pavement slowly deteriorated into the cratered single-lane roads shared with livestock, horses, and their owners, which mark most of the department’s more rural enclaves.

The team bounced along, silent due to difficulties maintaining conversation on such uneven terrain, and windows rolled up to avoid the dust swirling up from the little-used road. Half an hour later, the petite elderly woman who served as the group’s capable chauffeur, stretched up to look over the steering wheel as she slowed to veer around a group of three unexpected men: scouts for an international petroleum company running tests to look for oil. They rubbed the sweat off their faces with their branded denim long-sleeve shirts, and managed a wave, squinting out from under the shadows of their protective plastic helmets.

Closer to the community, the vehicle slowed in order to pass the children beginning the hour and a half walk home from the closest school, which just this year lost its budget for snacks, signifying a 8–9 hour stretch each day without food. One young boy, perhaps 12 years old, undertook the journey on the back of a cow whose skeleton stretched through the tufted hide. Judging by the passenger’s peals of laughter and teasing classmates, the transport was more for show than necessity.

The team arrived at the shared meeting space in the middle of the grass field, similar to those that mark the centers of most small rural communities in the region, and greeted one of the elderly community leaders.

¿Cómo está?

“Another day with hunger,” he replied. “But we have to move forward,” he added in the silence that followed his initial response, filling in the transition with hearty laughter, and gesturing to the team with a smile and an outstretched arm to enter the meeting space.

After roughly an hour of calls to community leaders who had forgotten about the meeting—calls made by walking around the grass field until one bar of cell signal appeared—chit-chat about the state of relations between the two parts of the community, excuses given for absences, and the arrival of new unexpected faces, all present began to get down to business. Over the next two hours participants sketched out how they would mobilize to petition various government agencies to meet state obligations of collective reparations to the community as part of the long process of building peace after war.

While one community does not a country make, the road to Ronce/r/svalles certainly illustrates the many challenges that Colombia faces with building a post-peace accord society in the most conflict-affected regions of the country. First, re-victimization of those who have suffered greatly at the hands of all varieties of armed actors is not uncommon through poorly managed victims’ reparations processes (e.g., relocation to sites that flood). Second, competing and often urgent needs among different kinds of victims, as well as particularities in each case of victimization, undermine both large-scale collective action and small scale quotidian life (e.g., communities divided into factions, fighting over limited resources). Third, tense and, frankly, often bizarre relations with the state—e.g., having to pass through a military base to arrive at a community—stymie governmental attempts to build trust and provide services to those affected by the armed conflict. Rampant local corruption poisons whatever good-faith efforts emerge and land titling remains cripplingly contentious. Fourth, international oil and mining interests exploit the poorly-regulated lands and the often vulnerable—though by no means powerless—people who occupy them (e.g., speculators such as those encountered on the road). And fifth, organizing communities at the margins of sociopolitical, economic, and even geographic life is profoundly complicated for many reasons. These reasons include, though are certainly not limited to, long histories of exploitation at the hands of outsiders and damaging failures in basic domains of public life, such as education and public health. In the midst of it all, more and more domestic and international interventions have begun to crowd the landscape, navigating both the literal and metaphorical hostile terrain. And in the many inevitable successes and failures to follow, we will better understand the stakes of life in transition for those in regions such as Caquetá, Colombia.

Fin

The contents of this blog do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Latin American Studies or the University of Chicago.

Apr 1, 2016 |

Pablo Palomino, Postdoctoral Lecturer, Center for Latin American Studies/History

This past March 24 marked the 40th anniversary of the coup d’état of 1976, providing, like every March 24, an opportunity for Argentina to re-elaborate the links between past and present. Too somber and fateful was that March 24, 1976, that changed the course of Argentine history irremediably. And history was very much alive this time, due to three converging circumstances.

The first is Argentina’s judiciary progress over the past decade regarding the violations of human rights during the State Terrorism of 1976–1983. More than 600 perpetrators of violations to human rights, mostly members of the military and other armed agencies, were condemned by federal courts to sentences ranging from less than three years to life sentences. (Another 300 cases, i.e., one out of three accused, were either absolved, dismissed, or are still in process). This is the result of a history, still ongoing, that started in 1985 with the trial sponsored by President Raúl Alfonsín that condemned the top military commanders—a trial based on the 1984 report Nunca Más and on the evidence collected by the Argentine human rights movement since the very beginnings of the dictatorship. The 40th anniversary of the Coup was hence an opportunity to remember the thousands of missing loved ones, and to publicly support a successful process of justice.

The second circumstance was related to the recently elected government of President Mauricio Macri, a political leader hostile to the human rights cause. Macri’s campaign rhetoric included the critique of what he called “el curro de los derechos humanos” (“the human rights scam”), referring to the close relationship between the human rights movement and the administrations of Néstor Kirchner (2003–2007) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007–2015) under which most of that process of justice took place. Once in office, the new government began dismantling state agencies, such as the Human Rights Office at the Central Bank, that had been mandated to provide evidence to support the judiciary in a further step: the investigation of the civilian and economic accomplices of the military government. The anniversary happened thus in the midst of a shift in official policy vis-à-vis the past.

Finally, and unexpectedly, President Barack Obama’s visit to Argentina was planned precisely for March 24—Macri’s advisors probably prioritized the visit over any concern about such an awkward date for a visit by the US President. After 12 years of a rather distant relationship with the Kirchners, the US diplomacy decided to support its new hemispheric ally with a presidential visit, giving the anniversary of the coup an unexpected geopolitical twist. White House officers, in view of the date, anticipated that Obama would order the declassification of official US documents regarding the dictatorship. Obama flew to Buenos Aires directly after his historic visit to Cuba. On the morning of March 24, as French President François Hollande had done in February, Obama visited Buenos Aires’ Parque de la Memoria, a quiet and windy edge of the city on the shore of the Rio de la Plata, turned by virtue of mesmerizing art works and architectural devices into an urban symbol of human rights. Obama threw flowers to the river, in homage to the men and women who, sedated and chained inside bags, were thrown there from military airplanes in the 1970s. But whereas Hollande was accompanied by the Madres and Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo and human rights activists, in recognition to the support given by France’s Socialist Party to their cause in the 1970s and 1980s, the US head of state was joined by Macri alone—no human rights organization attended the ceremony.

Why did human rights organizations turn their back to Macri and Obama, and why, despite that rejection, did both presidents decide to visit the Parque de la Memoria anyway? How should we interpret the two parallel policies, the one by Macri blocking the prosecution of civilian and economic accomplices of state terrorism, and the one by Obama to declassify military and intelligence files in favor of historical truth? What do the human rights of the 1970s mean to both countries today?

France and the United States are two countries at war against an enemy represented as the nemesis of Western freedoms. Human rights are the ultimate moral justification in the international arena against terrorism, and Argentina represents an essential chapter in that history. Paying homage to the desaparecidos became thus essential to Argentina’s friends—as essential as Jorge Luis Borges, dancing tango, or kicking a soccer ball. But since Macri’s political biography never intersected the human rights agenda, his words and gestures that day were odd and elusive, avoiding words like “military” or “desaparecidos” and instead blaming the past on “intolerance” and “divisions among Argentines,” expressions he routinely uses to criticize opponents. Macri’s support of the imprisonment of social activist Milagro Sala and the formulation of a repressive security protocol by the police to handle public demonstrations—a step backward from the peaceful tactics adopted after the massacres of demonstrators during the crisis of 2001–02—turned the human rights movement away from him. And yet, paradoxically, the presence of both heads of state at the Parque de la Memoria was a sign of that movement’s success in the public sphere.

Obama’s remarks at the Parque invoked the longer history of US Democratic administrations in this realm. He mentioned the role of the State Department under President Carter (1977–81) in support of the human rights movement, specifically through the pressure on the military by Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights Patricia Derian, and the invaluable collection of data on disappeared citizens by diplomat Tex Harris at the Buenos Aires embassy. He reaffirmed the orders he gave in anticipation of his visit: like President Clinton in the late 1990s, he ordered the declassification of US documents, this time not from the State Department but from the Pentagon and the CIA. The awaited official recognition of the role of the US in the coup, however, did not happen. The fact of being in Argentina on such a symbolic date, exactly 40 years after the events, was apparently not enough to make that decisive step forward. Nor was the proven fact, recognized by historians in both countries, of the explicit blessing of the coup and its human rights violations by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. President Obama just said the US had been “slow to speak out for human rights” and referred to its stance in 1976 vis-à-vis the Argentine coup as a matter of “controversy” still requiring examination. He focused the visit, like Macri, on “the future:” economic relations and security cooperation, with respect for human rights. Some local and international press misleadingly took these as words of autocrítica and regret, but Obama’s remarks carefully avoided both.

Human rights appeared hence as more of a rhetorical instrument—with potential judiciary consequences in the very long term—than an actual matter of diplomacy. This reflects a particular balance of forces both in the US and in Argentina regarding the links between past and present. The history of the coup d’état and the state violations of human rights is an uncomfortable one to some Argentine domestic constituencies and policies, as well as to the ethical conundrums of US policies in Guantánamo, Honduras, and the Middle East.

A crowd flooded the Plaza de Mayo in the afternoon. Like every March 24, a multitude of organizations, families, and individuals marched towards the pyramid at the center of the plaza, on top of which a statue of the Republic symbolizes the history of the fight for human rights that started in 1977 right there—the epicenter of previous histories as well, from the recovery of democracy in 1983 back to the Independence Revolution of May 25, 1810, the one that gave the colonial Plaza Mayor, then de la Victoria (for the popular victory against the British invasion of 1808) its current name, de Mayo. The Obamas had by then flown to Bariloche, in the Andes, to take a rest before returning to Washington, DC. But there they received a final visit from Macri and his wife, doubling their diplomatic alliance as personal friendship. Hence, while a multitude commemorated the National Day of Memory, Truth and Justice—a day of mourning and remembrance of which the public TV channel offered no coverage—Macri posed exultant before the cameras with the POTUS. It was perhaps the most egregious contrast of this last March 24. Two rituals of power taking place simultaneously (1)—the mise en scene of an alliance between the presidents of Argentina and the US while the collective remembering of the citizenry took place at the plaza—in one more chapter of the convoluted history of hemispheric relations.

Far from settled, human rights in Argentina and the rituals that surround them are history still in the making. I take the expression “rituals of power” from Pablo Ortemberg’s Rituales del poder en Lima(1735–1825): de la monarquía a la república (Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, 2014), to illuminate the changes and continuities enabled by official ceremonies and gestures.

Buenos Aires, Madres de Plaza de Mayo, 1981. Archivo General de la Nación, Argentina, Inventario 348582.

Buenos Aires, Madres de Plaza de Mayo, 1981. Archivo General de la Nación, Argentina, Inventario 348582.

Vera Jarach and portrait of her disappeared daughter, Franca. Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos, Argentina. Wikipedia Commons.

Vera Jarach and portrait of her disappeared daughter, Franca. Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos, Argentina. Wikipedia Commons.

Footnotes

I take the expression “rituals of power” from Pablo Ortemberg’s Rituales del poder en Lima (1735–1825): de la monarquía a la república (Pontifica Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, 2014), to illuminate the changes and continuities enabled by official ceremonies and gestures.

Please note:

The contents of this blog do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Latin American Studies or the University of Chicago.

Nov 26, 2014 |

On September 26, 2014, forty-three students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers’ College of Azotzinapa went missing after clashing with police during a protest. They were arrested and subsequently handed over to the Guerreros Unidos crime syndicate. All forty three are assumed dead, although there has been no official confirmation. The morbid disappearance of the normalistas has not only shed light on the thinly veiled involvement of the Iguala government with criminal cartels, but has also become the largest political scandal of Enrique Peña Nieto’s presidency.

As part of a day-long, two-session event on these troubling developments, the Center for Latin American Studies cosponsored “Violence Crisis in Mexico: The Case of Ayotzinapa” in conjunction with Latin American Matters, the Katz Center for Mexican Studies, and the Pozen Family Center for Human Rights. Comprising the afternoon session, Mauricio Tenorio of the University of Chicago, Guillermo Trejo of the University of Notre Dame, and Arturo Cano of La Jornada, spoke on issues of governance, corruption, and possible programmatic responses. Check out a link to a video of the session here and the audio recording here.

In the evening, Benjamin Lessing of the University of Chicago and Arturo Cano drew on their interests in comparative politics, cartel violence, and Latin America to lead a roundtable discussion on the events of Ayotzinapa followed by a Q&A with students.

Figure 1. Morro da Luz, picture taken by the author, April 2019

Figure 1. Morro da Luz, picture taken by the author, April 2019 Figure 2. A pastor and an armed drug dealer talking, favela da Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Picture by Alan Lima, published October 19, 2017, available at https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/10/13/album/1507850793_088715.html#foto_gal_1.

Figure 2. A pastor and an armed drug dealer talking, favela da Maré, Rio de Janeiro. Picture by Alan Lima, published October 19, 2017, available at https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2017/10/13/album/1507850793_088715.html#foto_gal_1.

Buenos Aires, Madres de Plaza de Mayo, 1981. Archivo General de la Nación, Argentina, Inventario 348582.

Buenos Aires, Madres de Plaza de Mayo, 1981. Archivo General de la Nación, Argentina, Inventario 348582. Vera Jarach and portrait of her disappeared daughter, Franca. Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos, Argentina. Wikipedia Commons.

Vera Jarach and portrait of her disappeared daughter, Franca. Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos, Argentina. Wikipedia Commons.