Oct 23, 2018 |

Keegan Boyar, Doctoral Candidate, History

Late one night this past summer, I was in the back seat of an Uber, returning home along the streets of Mexico City. Chattier than most, the driver asked what brought me to Mexico. I told him that I was here for dissertation research. “What’s your project?” he asked. “Well,” I said, trying to think of how to summarize it quickly and wondering how well it would go over in my functional but inelegant Spanish, “I’m researching the history of law and policing in Mexico City in the late 19th and 20th Centuries.” “Oh, the police,” he scoffed. “You know, there’s only one word you need to know to understand the police here in Mexico. Do you know what it is?” “No, what?” I said. He dramatically turned his head to face me. “CORRUPTION!”

For the rest of the trip, he expounded at length on his views about the problems with the police in Mexico—their inefficacy, their insufficient training, their frequent use of violence, and above all, their corruption. Although there were some novelties (notably, he briefly suggested that the Freemasons were ultimately to blame, although he refused to expand on this), by and large it was nothing I hadn’t heard before. What might be termed the “police problem” is a well-known issue in Mexico City. The police are widely distrusted by the broader population, and many people have their own stories, or know the stories of friends or family, about police extortion, abuse, and incompetent and/or insufficient service. Such issues frequently come up in news and writing about the city, as well.[1] Throughout, there is often a certain tension in these stories, in that residents widely believe that the criminal justice system does not function, yet also frequently complain about the perceived lack of police.

I think about these stories often while I work on dissertation research. My project, to give a more complete description, examines the institutional and social construction of public order and security in Mexico City and the surrounding Federal District from about 1870 to 1950. These were years of dramatic upheaval. The capital went from a stagnant city of a couple hundred thousand residents, still mostly concentrated near the old colonial central district and surrounded by farmland and lakes, to a bustling metropolis of millions that sprawled outward, building over former farms and drained lake beds and absorbing many of the once-distant suburbs into the rhythms of urban life. With this urban growth came the perception of supposedly “new” problems, including crime, unequal access to public services, and urban poverty, as well as the development of “modern” institutions to deal with them, such as new legal codes and professional police. Yet the reach of these institutions remained limited. Many city residents lived in a state of quasi-illegality, their survival dependent on informal relations of clientelism and unofficial toleration from authorities that could be revoked at any moment. People used, debated, and at times resisted these institutions in a variety of ways, shedding light on the tensions between the formal order set forth by the state through legal codes and institutions, and the informal but no less regulated order carried out in the practices of daily life in the city. Ultimately, the conversation between informal practices and formal regulation came to be at the heart of everyday life in Mexico City, and embedded in the foundations of the Mexican state.

Figure 1. Much of my research has been in the National General Archive, or AGN, which is housed in the former national penitentiary–apt, considering my project.

Understanding the history of the “police problem”—and of police-public relations in general—is of course a major part of my project. As historians have shown, the Mexico City police (as well as laws and regulations more generally) largely functioned to target the urban poor and working classes for scrutiny, arrest, and abuse. Yet this did not preclude these same residents from trying to make use of the police and criminal justice system as they struggled to survive. Indeed, a variety of sources suggest that, while those who lived on the margins of society were the most likely to be victimized by police abuse, their marginal status limited their access to some other forms of authority, and they therefore often had to turn to the police to mediate their disputes or use the police in concert with other tools.[2] Meanwhile, residents of all classes in newly constructed, sometimes unlicensed neighborhoods on the outskirts of the expanding city frequently wrote in to request police services, complaining that they were targeted by criminals in the absence of police.[3]

It was this environment, where fear of crime met fear of police abuse, that gave shape to many of the documents that I have found in my research. One that stands out in particular comes from the personal correspondence of Félix Díaz, the nephew of the Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz and, prior to the Revolution, the police chief of Mexico City.[4] On August 18, 1910, a man named Carlos Espino Barros wrote a letter to Díaz. In it, he said that he had heard from an eyewitness about “a savage attack committed by several police against a decent young man, of recommendable appearance,” on August 16. He had come to suspect that the assault had been “a true crime,” and as the witness thought that the young man might have died of his injuries, Espino asked Díaz if that was in fact the case. Although Espino’s poor health prevented him from going in person to talk to Díaz, or going before a judge to press for an investigation, he invited the police chief to send “a person of your confidence and who you know to keep secrets” to his home to discuss the matter further with him. Discretion was of the utmost importance, Espino wrote, because “I do not want to provoke the vengeance of the alluded-to police”. Despite the danger, he wrote to inform Díaz to show him how “certain police” dealt with “defenseless drunks, above all if they are decent and find themselves far from the city center,” as was the case in the attack in question. In response to the letter, Díaz sent the head of the Reserve Police (the investigative branch of the police) to investigate its claims. After checking with other police officials, he concluded that the young man in question had not been killed or injured, and had been released the following day. The official also interviewed Espino, who said he had heard about the incident from a young woman whose address he did not know.

Figure 2. “First page of letter, Carlos Espino Barros to Félix Díaz, August 18, 1910.

AGN / Archivos Privados / Félix Díaz / Caja 7 / Exp. 61 / Fs. 704-705.

Several points stand out in the letter and Díaz’s response. Espino’s fear of reprisal for speaking out about police violence suggests the high degree of distrust many residents felt toward the police, as does his belief that “certain police” routinely mistreated those they arrested. Yet this distrust was not absolute: not only did Espino take care to specify that it was only “certain police” (and not a systematic problem), but the fact that he wrote to Díaz with the evident hope that the police chief would listen and take action demonstrates some level of trust in police authorities. Similarly, Espino’s emphasis that the victim was “decent,” and his charge that police especially targeted “decent” people who were drunk, suggests the ways in which social status shaped perceptions of policing. While the police regularly and violently arrested those who were drunk in public[5], this instance of police abuse was particularly intolerable because it transgressed class boundaries, subjecting a member of the “decent” classes to the same violence regularly meted out to the urban poor. It’s also possible that this concern was animated by anxiety over Espino’s own social status. Although he did not specify his work, he was literate in a society with high illiteracy, indicating more education than many, but lived in a predominantly working-class neighborhood. Clearly striving to assert his own respectability, he may have seen police violence against the “decent” classes as a sign of the fragility of his own social status.

Finally, Espino’s letter sheds light into how knowledge of policing was constructed. Discussions of police violence spread along social networks, as people discussed incidents they had seen or had heard about from friends, neighbors, or other city residents. Rumor and fact mixed with residents’ preexisting anxieties and prejudices. In many ways, the stories people told about police violence, corruption, and incompetence parallel the stories that are told by residents of Mexico City today. While Espino may not have thought that freemasons were ultimately behind everything (or at least he didn’t say so in his letter), had he been able to meet the talkative Uber driver, he may well have found many other areas of agreement.

[1] For instance, the author and journalist Héctor de Mauleón recently reported on a failed attempt to film a nighttime special in the neighborhood of Tepito, an area with a longstanding reputation for crime. Upon arriving and asking a passing police patrol if they would be patrolling there that night, the journalists were told that the police would not be back until the next morning “due to the insecurity.” http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/columna/hector-de-mauleon/nacion/una-cronica-involuntaria-de-tepito

[2] Working- and lower-class women, in particular, often had to turn to the police to intervene in domestic disputes, where the patriarchal power of the husband over the family normalized domestic violence against women. In one example from 1904, a woman asked the police to arrest her husband for verbal and physical abuse. However, the husband’s friends, family, and neighbors, variously claiming that there was no reason to arrest him or that they did not know why he was being arrested, intervened, allowing the husband to escape. Archivo General de la Nación (AGN) / Tribunal Superior de Justicia del Distrito Federal (TSJDF) / Siglo XX (S.XX) / Caja 14 / Exp 1067.

[3] For a 1916 example, see: Archivo Histórico de la Ciudad de México / Municipalidades / Tacubaya / Policía / Caja 374 / Exp. 36.

[4] The following information comes from: AGN / Archivos Privados / Félix Díaz / Caja 7 / Exp. 61 / Fs. 704-705.

[5] See, for example: AGN / TSJDF / S.XX / Caja 326 / Exp. 58694. In this case from 1904, police arrested a woman for public drunkenness and for supposedly attacking the arresting officer. She, in turn, argued that the police had assaulted her and she was merely defending herself. Despite medical examination revealing substantial evidence that she had been beaten, the judge threw out the charges against her but also refused to investigate the possibility of police abuse.

Dec 15, 2017 |

Chris Gatto, PhD Candidate, History

On Thursday, September 7, 2017, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake struck off the Pacific coast of Mexico, killing over 100 individuals and damaging thousands of homes in the southern states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Tobasco. This was the strongest earthquake the country had experienced since 1787. While earthquakes are a fairly common occurrence in Mexico, this particular event caused more alarm and destruction than could have ever been anticipated.

The earthquake struck at approximately 11:30 pm, and I acutely remember standing in the bathroom of my Airbnb in Oaxaca City, brushing my teeth and getting ready to go to bed. I was concluding nearly two months of archival research in Oaxaca for my dissertation, entitled “From Cochineal to Coffee: The Making of a New Rural Society in Miahuatlán, Oaxaca, 1780–1880.” The door to my small apartment began to shake violently, and my initial thought was that someone was trying to break in. As I walked over to see what was happening, I immediately fell to the ground, as the floor beneath me began to shake. The power in the city then went out, and in complete darkness it became all too clear to me and everyone else in the city what was occurring.

While my first thought was to text my anxious mother (before she uncovered the news of the earthquake on her own), I then began to consider how this would affect the work I still needed to get done. I was finishing nearly six weeks of research in the Archivo Histórico de Notarías, a vast archive inside the Church of Santo Domingo right in the heart of Oaxaca City. This archive is home to nearly 2,000 volumes of notarial documents from the early 17th century all the way up until the 20th century, including land purchases and rentals, wills, contracts, and inventories. Needless to say, this archive plays an essential role in my dissertation, which explores the dramatic agricultural transformation that occurred in the southern part of the state from cochineal to coffee cultivation over the course of the 19th century.

The Archivo Histórico de Notarías is now fully digitalized, but researchers still need to spend considerable amounts of time with the original documents, identifying book and page numbers before proceeding to the Dirección General de Notarías, an office located in the Ciudad Administrativa about 15 minutes outside of the city, to begin a complicated process (trámite) of requesting digital copies. While I knew the Archivo itself would be closed for several days (as it was, although thankfully with limited damage), I was also concerned about the Ciudad Administrativa, where I needed to travel with a flash drive to collect all the images I had been identifying over the past month.

-

-

The main square of the Ciudad Administrativa on an average day

-

-

Ciudad Administrativa after the earthquake

-

-

Ciudad Administrativa after the earthquake

The first image above depicts the main square of the Ciudad Administrativa on an average day, while the next two images reflect the damage suffered following the earthquake. Suffice it to say, these offices would not reopen for quite some time, as government workers refused to return to the campus until proper working conditions had been restored. I remember visiting the Ciudad Administrativa during that week, hoping I could find someone, anyone, that could help me gain access to the hard drive and expedite the transfer of images. However, I was promptly turned away, as they insisted I would have to return the following week. Unfortunately, I did not have another week, and I flew back to Chicago on September 16 with the sick feeling that so much time and effort had been expended for nothing. While I was determined to return to Oaxaca soon to complete my research, I knew there were further challenges I would eventually have to overcome…

-

-

Protests at the Ciudad Administrativa

-

-

Protests at the Ciudad Administrativa

The Ciudad Administrativa, along with the Ciudad Judicial, are the two largest government offices in Oaxaca. However, on any given day, access to these offices is severely restricted, since they become the site for a range of protests from different social organizations and unions across the region, including taxi drivers (taxistas), teachers’ unions (maestros), and indigenous rights activists. These groups block access to the Ciudad Administrativa in different and often inventive ways (as shown in the images above), and when this happens, nobody can enter or leave the campus until the groups disassemble. These protests have become so routine that the public has become accustomed to the disruptions and adjust their schedules accordingly. Whatever one thinks of the validity of these protests (I happen to be quite sympathetic), they cause significant disturbances in the life of ordinary residents in the city, and you will often hear people expressing sympathy for the causes but not necessarily the tactics.

In organizing my trip back to Oaxaca, I knew I would have to allow several days for a procedure that should only take a couple hours. On the week of October 23, 2017, I flew back to Oaxaca, allowing five days (Monday through Friday) to get my work completed. I anxiously checked my Twitter feed on an hourly basis to identify reports of potential blockades (bloqueos) at the government campus. As it turns out, I was able find a small window early Tuesday morning to enter the Ciudad Administrativa and complete the process of acquiring nearly 1,000 images that will hopefully form an important part of my dissertation. Shortly after I entered, the campus was closed off, and we could not leave until 6pm that evening. The campus experienced similar protests on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday of that week, and thus I was incredibly fortunate to find the small window that I did to get my work completed.

Researchers in Mexico and across Latin America face these types of logistical challenges on a regular basis, and I do not mean to suggest that what I have faced is unique or atypical in any way. But my work in Oaxaca does show how precarious the work of historians can be, given that we are forced to rely on documents that readily become available or unavailable according to shifting circumstances beyond our control. I hope my dissertation can make good use of the materials I have been lucky enough to uncover, and shed light on historical processes that help us better understand such a dynamic and important region of Mexico.

Feb 2, 2016 |

Karma Frierson, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Anthropology

If you’re dead set on seeing a black person, I can give you directions to where a black man is—I wouldn’t want you to go home disappointed. He’s always there, so you need not worry about dropping in while he’s out doing his shopping at Mercado Hidalgo. And truth be told, in these days as he gets older, he could use the company. If this were a century ago, I’d give you directions from the docks of the port. They were open then; but now they are inaccessible to those who do not have customs clearance. Or perhaps I’d give them to you from the train station. The Porfirian era building is still there, but that mode of transportation has fallen by the wayside. With no logical arrival point and the rapid expansion of the city that has led to over half a million people calling Veracruz home, I want to make sure you can find him. I suppose the easiest way I can direct you is from the zócalo, the main plaza of the historic center.

Veracruz’s zócalo, like many, is a vibrant place that locals and tourists simultaneously use in different ways. There is a wide open space that is generally empty in the heat of the day, a permanent stage, and a copse of bushes and palm trees surrounding crosscutting pathways that offer shade. If you face the stage, the municipal palace will be behind you and the famed portales with their roaming musicians ready to play a variety of genres including banda, mariachi, son montuno and son jarocho will be on your right. On your left will be the cathedral. Its recent coat of paint makes the façade stand out in a cityscape where old buildings are protected, but not preserved, and different architectural styles abut each other.

Go toward the cathedral, you will be moving away from the water and toward another flowing body—Calle Independencia. As you make your way out of the zócalo, the Hotel Diligencias —another allusion to an outdated mode of transportation—will be directly in front of you (1). Turn left, you’ll be going against the flow of traffic, alongside the church, and toward the Gran Café del Portal. You’ll see ambulatory shoe shines looking downward, trying to find someone in need of a polish, and marimba bands set up to play for the patrons who are taking their coffee outside under the lazily turning ceiling fans that futilely move the warm, humid air. You’ll have to cross the street and one of the fanciest looking McDonald’s in the area and keep going down Independencia for another block until you get to Calle Serdán and turn right. Not even halfway down the block you’ll see a diagonal callejón, take that. You’re almost there. I would say that the tree growing out of the abandoned building is a clear sign that you’re on the right path, but it’s a relatively common sight. You’ll be approaching him from behind, but trust me, the statue to Benny Moré isn’t going anywhere.

Go toward the cathedral, you will be moving away from the water and toward another flowing body—Calle Independencia. As you make your way out of the zócalo, the Hotel Diligencias —another allusion to an outdated mode of transportation—will be directly in front of you (1). Turn left, you’ll be going against the flow of traffic, alongside the church, and toward the Gran Café del Portal. You’ll see ambulatory shoe shines looking downward, trying to find someone in need of a polish, and marimba bands set up to play for the patrons who are taking their coffee outside under the lazily turning ceiling fans that futilely move the warm, humid air. You’ll have to cross the street and one of the fanciest looking McDonald’s in the area and keep going down Independencia for another block until you get to Calle Serdán and turn right. Not even halfway down the block you’ll see a diagonal callejón, take that. You’re almost there. I would say that the tree growing out of the abandoned building is a clear sign that you’re on the right path, but it’s a relatively common sight. You’ll be approaching him from behind, but trust me, the statue to Benny Moré isn’t going anywhere.

Fifteen years ago the Cuban government and people donated the first statue made of their native son to the people of Veracruz, where, as the sculptor noted, he could “walk among the people who adopted him (2). Benny Moré was immortalized in Callejón de la Lagunilla, a once vibrant space filled with dancing bodies and the sounds of son veracruzano de la raíz cubana—a musical genre originally from Cuba but wholly integrated in Veracruzan popular culture. The anchoring club is no longer open, and the dancing bodies have moved on, but Benny remains.

He is not the only Afro-Cuban honored in the historic center of Veracruz. There are plaques to the Cuban musicians Compay Segundo and Celia Cruz in the Plazuela de la Campana, another public space that still hosts four nights of dancing. What is more, Cubans are not the only Afro-Latinos memorialized. In the old neighborhood of La Huaca there is a statue to the famed singer Toña la Negra in the callejón named in her honor. She is, perhaps, the most famous Afro-Mexican there is and a source of pride for many locals in the port city. The most recent statue to be erected is also to an Afro-Mexican woman—La Negra Graciana, a world-renowned harpist in the son jarocho genre. A silhouette of her playing now stands in the heavily trafficked Callejón Trigueros, which links the zócalo to La Campana. The fact that there are statutes to people of African descent is not in itself noteworthy. Statues abound in the port city—along the malecón or boardwalk there are statues to the Spanish, Jewish, and Lebanese migrants. There are statues commemorating the soldiers who have fought and died in the four times Veracruz has been heroic. There is even a statue to Alexander von Humboldt. But the statues to the Afro-Latin American musicians are not on the water’s edge—they are within the lived spaces of everyday life in Veracruz. These statues—most of which were installed as part of government-sponsored cultural festivals—are permanent, inert ways in which locals are telling themselves and others about themselves.

The historic mid-census survey of 2015 was the first time Mexico officially counted its population of African descent. For those who work in Afro-Mexican Studies, the breakdown in percentages follows predictions. The highest percentage of self-identifying Afro-Mexicans are in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Veracruz, in that order. This is what has been reported in the international and national press, and with good reason. The municipality of Veracruz only had over 25,000 individuals who self-identified as Afro-Mexican and another 5,000 who said yes, in part. In such a large city, maybe you won’t encounter those individuals—or maybe you will and not realize it. However, you will, invariably, see persons of African descent cast in bronze, looking out over a population whose local culture acknowledges and valorizes the contribution of people of African descent, both Mexican and otherwise.

Footnotes

(1) Diligencias is a stagecoah or carriage used for transportaion.

(2) http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2001/08/25/08an1esp.html

Please note:

The contents of this blog do not necessarily reflect theviews of the Center for Latin American Studies or the University of Chicago.

Nov 2, 2015 |

By Emilio de Antuñano, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of History

My dissertation studies Mexico City’s growth in the years between 1930 and 1950, analyzing how different groups shaped the transformation of Mexico’s capital and—perhaps more significantly—were shaped by it. These questions first led me to Mexico City’s municipal archives, where I spent months looking at documents that recorded the conflicts between urban planners, government officials, political brokers, and associations of urban residents at a time of unforeseen urban growth. For the most part, these documents seemed bureaucratic and dry, in stark contrast with the boisterous corner of the streets of Cuba and Chile where the Archivo Histórico de la Ciudad de México stands. The movement and the noises of the street offered a reminder of life, a life which I was unable to find amidst the dusty papers of the archive, particularly during the initial months of my research.

This past summer, my research took me to a very different site, only two hours away from Chicago: the Library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where the Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers are located. Trained as an anthropologist, Oscar Lewis wrote extensively about small, “traditional” communities, cities, and the migration from one to the other that so deeply transformed the twentieth century. Ruth Lewis, a psychologist, conducted research alongside her husband, often gaining entrance into domestic spheres closed to him. Most significantly for my own research, Oscar and Ruth Lewis spent the larger part of the 1950s in Mexico City, studying the culture of the poor in Mexico’s infamous vecindades; two books—Five Families (1959) and Children of Sánchez (1961)—are the direct outcome of this research. The Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers hold a trove of wonderful ethnographic material: interviews, life histories, photographs, statistics, and detailed descriptions of some of Mexico City’s neighborhoods. As a whole, these materials provide a unique window into the life of Mexico City’s poor residents at the time.

Lewis travelled to Mexico City in 1951, after conducting extensive fieldwork in Tepoztlán. His findings there challenged the traditional, homogenous, and static community that anthropologist Robert Redfield had theorized through his concept of the “folk society.” Instead of stability and harmony, Lewis discovered a town rife with conflict and change, as illustrated by the migration to Mexico City. “I want to study the influence of “city people” [migrants from Tepoztlán in Mexico City] on Tepoztlán and vice-versa,” wrote Lewis in 1944 while explaining his new project to Ernest Maes. “Furthermore, Mexico City now has a population of about two million. Of these at least a million are from the out-skirts, from rural areas. In this sense the colony of Tepoztecans may be representative of many country people who came to Mexico. We should know what happens to these people when they come to the city.” (1)

Lewis’ papers illuminate how his experience in Tepoztlán—as an anthropologist studying a “primitive” culture—shaped the questions that he posed to Mexico City. There, Lewis conducted most of his research in a few blocks of Colonia Morelos, a universe that in his writings appears as self-contained and that he would get to know intimately. This vantage point is crucial for understanding his ideas; although many of the people that he met led lives full of adventure and movement—migrating from Mexico City to the United States, or from Tepoztlán to Mexico City—reading his books it sometimes seems that they always came back to the streets of Colonia Morelos, crossed by kinship ties. Based on this vantage point, Lewis argued that migrants in Mexico City did not suffer from the loneliness and alienation that sociologists expected but, on the contrary recreated relationships that could be traced back to their towns of origin.

The transcripts of The Children of Sánchez are, arguably, the highlight of the archive. This book is divided in four parts, each of them telling the story of one of Jesús Sánchez’s four children—Jesús’ own life story opens and closes the book. The book is written from a first-person perspective, extracted from the hundreds of hours of interviews that Oscar, Ruth, and their research assistants conducted. Woven together, these stories provide an extremely layered and nuanced history of a family (the reader gets, for instance, four or five viewpoints of significant events in the family history). Lewis claimed that he chose his informants based on their talent as storytellers and their fascinating lives but his presence in the transcripts of the interviews is evident. By interviewing the Sánchez, befriending them, and editing their voices, Lewis wrote a book that resembles a novel—this is not incidental, he discussed literary matters with John Steinbeck and took the Sánchez to an O’Neill play, in order to “help them see the level” he was after (2). The lines between art and method, fiction and social science, are very hard to draw.

These meditations struck me as I read the transcripts of Lewis’s long interviews with the Sánchez and realized that they do not include the names featured in the book—Jesús, Manuel, Roberto, Consuelo, and Marta Sánchez—but, rather, the “real” names of the people whose lives the book so intimately describes. (The names were changed to protect the identity of the family, mostly a futile measure, as some of the “Sánchez” embraced the limelight and acquired relative fame). Reading these names stirred me; they seemed capable of bringing me one step closer to the past. And this feeling only grew, becoming almost unbearable, when I discovered a folder with photographs of the “Sánchez.” Lewis was a marvelous photographer. He looked at his subjects as equals and friends, without distance or condescension. The portraits seemed familiar, as if picturing someone we knew, as if the camera was not betraying the people in the book. The relationship between words in print and images was uncanny.

Viewing these photographs represented a deeply touching experience. It was, in many ways, the reverse of my earlier experience at the Archivo Histórico de la Ciudad de México. Urbana-Champaign is a quiet and bucolic college town; Lewis’ archive is located around its southern fringe, in a library annex by a park that gently transforms into an endless landscape of cornfields. Nothing could be further apart from the busy corner of the streets of Cuba and Chile—or from the streets that Lewis described and photographed. Life seemed richer within the archive this time, amidst the papers and photographs.

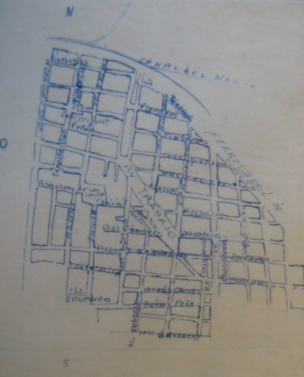

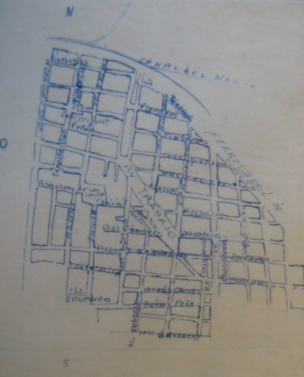

Sketch of Colonia Morelos. Unknown author. Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944–1967. “Peluqueros Census Data” (1956). Box 124.

Sketch of Colonia Morelos. Unknown author. Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944–1967. “Peluqueros Census Data” (1956). Box 124.

Footnotes

(1) March 9, 1944. Quoted in Susan M. Rigdon, The Cultural Facade: Art, Science, and Politics in the Work of Oscar Lewis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 198.

(2) Oscar to Ruth Lewis. July 1957. The Cultural Facade, 219.

Please note:

The contents of this blog do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Latin American Studies or the University of Chicago.

Go toward the cathedral, you will be moving away from the water and toward another flowing body—Calle Independencia. As you make your way out of the zócalo, the Hotel Diligencias —another allusion to an outdated mode of transportation—will be directly in front of you (1). Turn left, you’ll be going against the flow of traffic, alongside the church, and toward the Gran Café del Portal. You’ll see ambulatory shoe shines looking downward, trying to find someone in need of a polish, and marimba bands set up to play for the patrons who are taking their coffee outside under the lazily turning ceiling fans that futilely move the warm, humid air. You’ll have to cross the street and one of the fanciest looking McDonald’s in the area and keep going down Independencia for another block until you get to Calle Serdán and turn right. Not even halfway down the block you’ll see a diagonal callejón, take that. You’re almost there. I would say that the tree growing out of the abandoned building is a clear sign that you’re on the right path, but it’s a relatively common sight. You’ll be approaching him from behind, but trust me, the statue to Benny Moré isn’t going anywhere.

Go toward the cathedral, you will be moving away from the water and toward another flowing body—Calle Independencia. As you make your way out of the zócalo, the Hotel Diligencias —another allusion to an outdated mode of transportation—will be directly in front of you (1). Turn left, you’ll be going against the flow of traffic, alongside the church, and toward the Gran Café del Portal. You’ll see ambulatory shoe shines looking downward, trying to find someone in need of a polish, and marimba bands set up to play for the patrons who are taking their coffee outside under the lazily turning ceiling fans that futilely move the warm, humid air. You’ll have to cross the street and one of the fanciest looking McDonald’s in the area and keep going down Independencia for another block until you get to Calle Serdán and turn right. Not even halfway down the block you’ll see a diagonal callejón, take that. You’re almost there. I would say that the tree growing out of the abandoned building is a clear sign that you’re on the right path, but it’s a relatively common sight. You’ll be approaching him from behind, but trust me, the statue to Benny Moré isn’t going anywhere.

Sketch of Colonia Morelos. Unknown author. Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944–1967. “Peluqueros Census Data” (1956). Box 124.

Sketch of Colonia Morelos. Unknown author. Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944–1967. “Peluqueros Census Data” (1956). Box 124.