Andrew Packman (University of Chicago) joins the roundtable with his essay, “Enhancing Racialized Social Life: The Implicit Spiritual Dimension of Critical Race Theory.” Packman’s post asks what it means to enhance life generally by asking what it means to enhance racialized social life specifically. It explores two rival versions of critical race theory and argues that, despite their manifold differences, they each possess an implicit spiritual dimension. This serves as the basis for a potentially illuminating engagement between critical race theory and Christian theology.

The November-December issue of the Forum features the Enhancing Life Project, which takes aim at addressing one of the most basic human questions—the desire to enhance life. This desire is seen in the arts, technology, religion, medicine, culture, and social forms. Throughout the ages, thinkers have wondered about the meaning of enhancing life, the ways to enhance life, and the judgments about whether life has been enhanced. In our global technological age, these issues have become more widespread and urgent. Over the last two years, 35 renowned scholars from around the world in the fields of law, social sciences, humanities, religion, communications, and others, have explored basic questions of human existence. These scholars have generated individual research projects and engaged in teaching in Enhancing Life Studies within their fields, as well as contributed to public engagement in various ways.

Over the next month and a half, Enhancing Life scholars associated with the Divinity School will share essays and reflections on the Enhancing Life Project that will explore its implications for their own scholarship and teaching. We invite you to join the conversation by submitting your comments and questions below.

Posted Essays:

- William Schweiker, Enhancing Life and the Forms of Freedom

- Anne Mocko, Attending to Insects

- Kristine A. Culp, “Aliveness” and a Taste of Glory

- Heike Springhart, Vitality in Vulnerability: Realistic Anthropology as Humanistic Anthropology

- Andrew Packman, Enhancing Racialized Social Life: The Implicit Spiritual Dimension of Critical Race Theory

- Michael S. Hogue, Resilient Democracy in the Anthropocene

- Darryl Dale-Ferguson, Envisioning a Fragile Justice

The Enhancing Life Project was made possible by a generous grant from the John Templeton Foundation, and the support of the University of Chicago and Bochum University, Germany.

by Andrew Packman

If we are to ask what it means to enhance life, then surely we also need to ask about those forces that degrade life and retard its enhancement. In theological terms, we might say that to talk about salvation demands that we also talk about the sin from which we need saving.

To speak of racism as a sin is hardly to overstate the matter. This evil stained American life at its founding and, to this day, it has proven to be as recalcitrant as it is vicious. We can acknowledge that, over the course of American history, racial group identities have proven to be fluid and permeable.1 The forms of racial domination have been similarly manifold and malleable.2 But the undeniable fact remains that racial structures and dynamics have profoundly impacted American social life at every level, and their legacy is anything but innocent.3 At the very least, the racial contours of American life unjustly disadvantage non-white persons, and at worst, they have motivated and justified their enslavement and murder. Despite the notable social and legislative progress in race relations over the past several centuries, race continues to figure prominently in the access to basic human goods, in the social dynamics that inform where we live and whom we love, and even in how we conceive of our selves and our own possibilities for life. To neglect the racialized character of American life is simply to misunderstand it. And that makes the work of enhancing our common life much more difficult.

In what follows, I approach the question of enhancing life generally by asking what it would mean to enhance racialized social life specifically. First, I explore two competing trajectories of critical race theory in order to get the particular moral and political challenges posed by American racism into view. Then I turn to consider each trajectory from the perspective of Enhancing Life Studies. According to the Principal Investigators of the Enhancing Life Project, “one of the most profound spiritual capacities human beings possess” is the imaginative aspiration to enhance life.4 While this spiritual capacity is among the “definitive qualities of the human species,” they contend that it often remains “an implicit aim in many cultural, technological, and spiritual processes.”5 Specifically, their claim is that these social and cultural processes, including academic ones, implicitly aim to enhance life insofar as they 1) project imaginative “counter-worlds” that challenge and evaluate the status quo, 2) diagnose the forces that degrade life, and 3) propose models of individual and social change that aspire “to move persons and communities into the future.”6 With this account of the “spiritual” in hand, I argue that these trajectories of critical race theory do, in fact, bear implicit spiritual dimensions. And I conclude by sketching one way in which this insight might open up new, ethically illuminating horizons for an engagement between critical race theory and Christian theology on the question of what it means to enhance racialized social life.

Despite a dizzying array of methods, critical race theorists all seek to understand the role that race plays in structuring and representing social life. The qualifier “critical” signals that these theorists are unanimously suspicious of the original biological conception of race. Instead of biological kinds, they see racial groups as historically contingent, socially constructed, politically charged categories for classifying human beings on the basis of genealogically inherited, phenotypically expressed qualities like skin color, hair texture, facial features, etc. A long-standing disagreement persists between those theorists who view racial life primarily in terms of social structures and material conditions and those who focus on the ideational and social psychological dynamics of race and racism.7 I’ll refer to them respectively as structural-materialists and volitional-idealists.

Charles W. Mills’s work exemplifies the structural-materialist position. He diagnoses the basic problem of racialized life as a matter of exploitative social structures. On his account, the United States’ political economy is so ordered as to transfer material benefits from nonwhite people to white people, principally through mechanisms of exclusion.8 In contrast to its professed ideal structure of enlightened moral egalitarianism, Mills argues that the real structure of the United States was actually premised upon a more basic, racialized distinction between persons and subpersons.9 Persons are those who deserve moral respect and equal treatment under the law. So long as personhood is restricted to white people, institutions like chattel slavery and the expropriation of Native American lands can be understood, not as “anomalies” in American history, but as the predictable result of a polity fundamentally structured by white supremacy. Though these structures are no longer quite so overt and explicit, Mills argues that they remain the de facto norm of American social life that explains the vast differentials in wealth, income, and access to other human goods.

Mills contends that although white supremacy is a material structure, its social effects flow from political economy into the psychological realm.10 In Marxist parlance, this is an account of ideology.11 Under white supremacy, members of racial groups tend to live in racially segregated enclaves, be subject to racially segregated experiences, and, crucially, their moral psychologies will be formed in racially generalizable ways. For white people ensconced in homogenous white environments, the capacity to empathize with nonwhite people, to perceive the racially salient features of moral situations, or even to perceive nonwhite people as persons worthy of moral respect are all significantly diminished. These racially distinct cognitive impairments make white people, generally speaking, less responsive to the moral claims of nonwhite people.

This insight informs Mills’s account of enhancing racialized social life. He insists that no amount of moral exhortation will lead to transformation, be it individual or social. The moral arguments will, generally speaking, fall on deaf white ears. He is not entirely deterministic on this score; he admits that white people can resist and overcome their structurally deficient moral psychology. But his claim is that this will never be sufficient for the kind of social transformation he has in mind. To achieve anything approximating racial justice, Mills suggests that we focus primarily on transforming “largely ‘material’ politico-economic factors.”12 He argues for racial reparations and job-training programs that seek to dismantle the structural and material “supports for whiteness”13 which preserve the white political advantages that makes whiteness psychologically alluring in the first place.

So, while Mills’s account of racialized social life is structural-materialist in orientation, he does not neglect the need for individual, psychological transformation. He simply argues that the condition for the possibility of individual change in matters of race is a prior change in structural-material conditions.

Jorge Garcia is the most prominent proponent of the opposing volitional-idealist model, which he calls a “volitional account of racism.”14 He locates the basic problem with racialized life, not in social structures, but in the affective and volitional depths of individuals. For Garcia, racism lies in the “heart,” in our desires, intentions, and emotions. It comes in two principle forms. The most vicious kind is “a hatred, ill-will, directed against a person or persons on account of their assigned race.”15 But not all racism is so clearly vicious. A derivative form of racism lies in “callous disregard”16 for a person’s welfare on account of their race. The common denominator of these two varieties of racism is that they are both moral vices. In various ways, they fall short of moral virtues like benevolence and justice.

Even with his emphasis on the interior lives of individuals, Garcia remains deeply concerned with institutional or structural dimensions of racism. But unlike the structural-materialist, Garcia thinks that institutions are racist only if they are motivated by racial ill will or callous disregard. That is, social structures are made racist by their intentional inputs not their consequentialist outputs. Structures or institutions that lead to disproportionate harm to members of a particular race are certainly unfortunate, and morally virtuous persons should be concerned about them.17 But if those institutions or structures lack racist intentions, they do not deserve the moral opprobrium that rightly accompanies charges of racism.

For the volitional-idealist, attempts to enhance racialized social life must attend to individual hearts and minds. Structures are transformed when the individuals who maintain or tolerate them are themselves morally transformed. That which enhances racialized life, then, is something like an individual and collective change of heart. This calls for training in virtue, the eradication of racial disaffections (both ill will and callous disregard) and a cultivation of anti-racist attitudes (goodwill toward racial others, genuine friendship, and solidarity).18 Thus we have a reversal of the structural-materialist position. A change of heart is the condition for the possibility of transforming racist social structures. As the volitional-idealist might put it: How will these sweeping changes to social structures ever come to pass without benevolent and just individuals who are concerned about the welfare of the racially marginalized?

So far, I’ve shown that these two branches of critical race theory share a common concern and aspiration; they both seek not only to understand, but also to enhance, racialized social life. By borrowing categories from Enhancing Life Studies, the significance of this claim comes more clearly into view. First, we have seen that each offers a diagnosis for what principally degrades racialized social life. The structural-materialist identifies the central problem as exploitative transpersonal social structures, whereas the volitional-idealist points to moral vices like racial hatred and callous disregard. Second, each imagines an anti-racist counter-world that challenges the status quo. Charles Mills imagines a social order marked by the eradication of those structures that make whiteness politically advantageous, and Garcia envisions a world in which racist animus is purged from each individual soul and replaced by racial solidarity and friendship. Finally, each presents a model for personal and social change. Mills argues that the material order must be transformed by political action before Garcia’s collective change of heart becomes possible, and Garcia argues that Mills has placed the cart before the horse. In sum, although these two trajectories of critical race theory bear manifest differences, they share an implicit spiritual dimension in that each aspires to enhance racialized life and each manifests this aspiration in the ways theorized by the Enhancing Life Project.

The real significance of this claim, however, is not simply to show that there happen to be spiritual dynamics at play in American racism and in the scholarly disciplines that theorize about it. The bolder, more interesting claim of Enhancing Life Studies is that, by rendering this spiritual dimension of various cultural processes explicit, a new basis and vector for scholarly inquiry might emerge that includes religious and theological insights. The basic aspiration to enhance life is, of course, one that members of religious traditions have long pondered and, at their best, rendered articulate. Like the critical race theorists above, the great religions of the world have made diagnoses of life-degrading forces (Christians call them sin), projected counter-worlds that challenge the status quo, (Christians call that the kingdom of heaven), and articulated models for personal and social change (Christians call that conversion).

So what difference does it make that critical race theory and, in this case, Christianity, both dabble in the spiritual? In the space that remains, I will sketch one such implication, but only one.

Notice that both varieties of critical race theory make claims about moral agency. The structural-materialist emphasizes the degree to which white supremacy creeps into our cognitive processes and constrains moral agency. The volitional-idealist, on the other hand, insists that human beings, even those who hold racist sentiments in their hearts, are capable of moral conversion. The synthetic picture that emerges from these accounts depicts human beings as bound and yet free, largely constrained by social, historical, and political horizons – and yet stubbornly drawn beyond them.

The Apostle Paul also tried to make sense of what binds human beings and what ultimately frees us. But his view is, ironically, both more cynical and more hopeful than that of critical race theory. In his Letter to the Romans, he writes: “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing that I hate” (Romans 7:15). And furthermore, even “when I want to do what is good, evil lies close at hand.”(v. 21). For Paul, the forces that frustrate and constrain moral agency are not merely social and political; rather, they permeate human existence as a basic structure.

From this perspective, we might question the structural-materialist’s suggestion that a social revolution will occasion individual conversions. After all, to eradicate the social structures that condition human nature is not to eradicate human nature itself. And while Paul would agree with Garcia that a change of heart is crucial, he would also insist that, far from spelling the end of the struggle against racism, conversion marks the beginning of the spiritual struggle between flesh and spirit. The one who knows the good but does not do it comes to this moral knowledge only after their change of heart. And here, the structural-materialist’s insights into the complexity and social embeddedness of these forces become especially poignant.

This admittedly paints a rather dire picture. But Romans 7 does not end with the “abyss of the will.”19 It is precisely in this abyss that a new ground begins to appear. “Who will save me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord.”20 This theological horizon reveals another agency besides the human to be on the scene, stubbornly and graciously drawing us beyond our limits.

The devil is in the details, of course. Critical race theorists might note that even the theological symbols of “flesh” and “spirit” bear a markedly racialized valence.21 They might also note the long history of theological construals that serve to evade and enervate rather than energize responsible, life-enhancing action. And they would be right to do so. The engagement I am proposing between critical race theory and Christian theology must be mutually critical and mutually edifying. My own dissertation attempts this, and there I argue that thinking about racism as a sin of disordered affections and spiritual blindness actually sharpens and clarifies the call of responsibility in racial matters. I clearly cannot defend that claim here. But I hope that by exposing the spiritual dimension of critical race theory, I have shown that an engagement between these fields is both possible and, potentially, ethically enriching. ♦

Andrew Packman is a doctoral candidate in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His research focuses on theological construals of moral agency and the role of affectivity in the moral and religious life. He is currently writing a dissertation that asks why American racism has proven so recalcitrant to moral suasion and political subversion, and he addresses this moral problem by integrating insights into the nature of moral agency from critical race theory and Schleiermacher’s ethical and theological writings. Andrew also holds an M.Div. from the University of Chicago and is ordained in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).

Andrew Packman is a doctoral candidate in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His research focuses on theological construals of moral agency and the role of affectivity in the moral and religious life. He is currently writing a dissertation that asks why American racism has proven so recalcitrant to moral suasion and political subversion, and he addresses this moral problem by integrating insights into the nature of moral agency from critical race theory and Schleiermacher’s ethical and theological writings. Andrew also holds an M.Div. from the University of Chicago and is ordained in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).

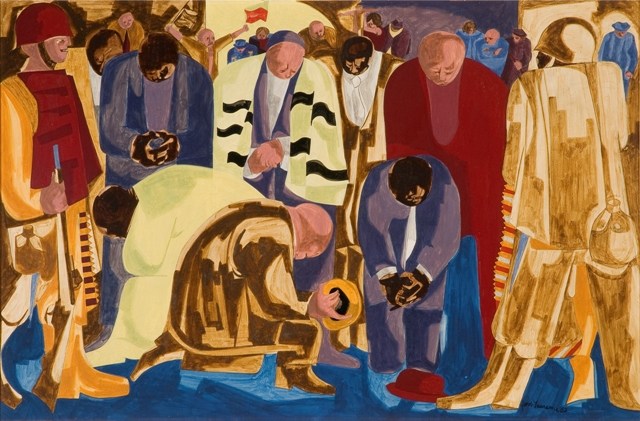

* Feature image: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) “Praying Ministers,” 1962.

- For example, the Irish were not always white. Cf. Noel Ignatiev. How the Irish Became White (New York: Routledge, 1995). ↩

- So while chattel slavery, Jim Crow laws, discriminatory lending practices, and implicit racial bias are all examples of racism, they are not simply the same thing. ↩

- While the focus of this paper is strictly the transformation of the socially deleterious aspects of racialized life in the United States, it is important to note that the process of constructing, inhabiting and reinterpreting racial categories has also created the conditions for all manner of social goods, including “linguistic innovations, jokes, styles, food, music {…} that are racialized” and that “provide multiple sources of gratification and fulfillment” and “more affirmative mode{s} of investment in racial belonging.” Mustafa Emirbayer and Matthew Desmond, The Racial Order (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 17. ↩

- The Enhancing Life Project. “Project Description. The Big Questions.” Accessed December 12, 2017. http://enhancinglife.uchicago.edu/about/the-big-questions. ↩

- Ibid., “Project Description. Introduction: The Big Questions.” Accessed December 12, 2017. http://enhancinglife.uchicago.edu/about/introduction-the-big-questions ↩

- The Enhancing Life Project. “Project Description. Introduction: The Big Questions.” Accessed December 12, 2017. http://enhancinglife.uchicago.edu/about/introduction-the-big-questions. ↩

- With that said, some theorists explicitly set out to resist this either/or and pursue an integrated, synthetic account of racial oppression. Cf. Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States: from the 1960s to the 1990s (New York: Routledge, 1994) and more recently Mustafa Emirbayer and Matthew Desmond, The Racial Order (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). ↩

- Charles W. Mills, “Racial Exploitation and the Wages of Whiteness” in The Changing Terrain of Race and Ethnicity, ed. Maria Krysan and Amanda E. Lewis (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004), 235-262. ↩

- Charles W. Mills, “Revisionist Ontologies: Theorizing White Supremacy,” in Blackness Visible: Essays on Philosophy and Race (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 97-118. ↩

- Charles W. Mills, “White Right: The Idea of a Herrenvolk Ethics,” in Blackness Visible: Essays on Philosophy and Race (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 139-166. ↩

- Mills is explicit about this connection to Marxist theory, although he eventually breaks with Marxism . Cf. Mills, From Class to Race: Essays in White Marxism and Black Radicalism (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003). ↩

- Charles W. Mills, “Whose Fourth of July?: Frederick Douglass and ‘Original Intent,’” in Blackness Visible: Essays on Philosophy and Race (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 167-200. 200. ↩

- Charles W. Mills, “White Supremacy and Racial Justice,” in From Class to Race: Essays in White Marxism and Black Radicalism (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 217. ↩

- Jorge L. A. Garcia, “The Heart of Racism,” The Journal of Social Philosophy 27, No. 1 (Spring, 1996): 5-46. ↩

- Garcia, “The Heart of Racism,” 6. ↩

- Jorge L. A. Garcia, “Current Conceptions of Racism: A Critical Examination of Some Recent Social Philosophy,” The Journal of Social Philosophy 28, No. 2 (Fall, 1997): 5-42. 19. ↩

- “Not to care about the rights of people offends against the moral virtue of justice, and to be uncaring on racial grounds shares in this moral deformity.” Jorge L. A. Garcia, “Philosophical Analysis of the Moral Problem of Racism,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 25, No.1 (September, 1999): 1-32. 20. ↩

- Garcia, “Philosophical Analysis of the Moral Problem of Racism,” 20. ↩

- I owe this turn of phrase to Hans Jonas, “The Abyss of the Will: Philosophical Meditation on the Seventh Chapter of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans” in Philosophical Essays: From Ancient Creed to Technological Man (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1974). ↩

- Romans 7:24-25. (NRSV) ↩

- For an insightful account of the complex connections between Enlightenment theories of race, modern political theory, and theological construals of Christ’s flesh, cf. J. Kameron Carter, Race: A Theological Account (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), especially Ch. 2. ↩