The vast majority of the volumes within the Taschenbücher collection were published before German unification and at a time where there were many competing German-speaking nation states. The largest and most politically dominant of these were the Hapsburg Empire, centered in Vienna, and Prussia, centered around both Königsberg and Berlin. Indeed, this fractious political situation made for a troublesome literary one: well into the 1830s, there were hardly any copyright standards, with books being pirated and republished in other, independent states with no recompense to the original authors and editors. Some publishers even undertook to print in two cities, hoping to secure proceeds from two distinct markets, like Franz Riedl’s Witwe & A. Liebeskind in both Vienna and Leipzig (then, perhaps, the center of literary publishing during the height of the Taschenbuch).

L’Almanach des Muses 1765 (left): The German Musenalmanache, the form which eventually gave way to the Taschenbuch, owe their inspiration to the Francophone Almanach des Muses like this one published in Paris in 1765. This particular edition, also found in the University’s Special Collections, had a powerful influence not only on French culture but also throughout Europe and in particular in Germany where the Musenalmanach would soon thereafter take particular hold. Almanach der deutschen Musen auf das Jahr 1770 (right): One of the first Musenalmanache released in Germany, this edition, published by a firm in Leipzig, here unnamed, is actually a pirated copy (with a few editional poems included) of the Musenalmanach of Göttingen, published in the same year. This publisher had acquired the uncorrected proofs of the Göttingen almanac through a journeyman printer and was actually published four weeks before the edition it had ripped off. Despite the piracy at its origin, this edition reflects the beginnings of the Taschenbuch form in Germany and highlights the struggles faced by honest editors, writers, and publishers alike in a time before abuses of intellectual property could be duly punished in the German-speaking world.

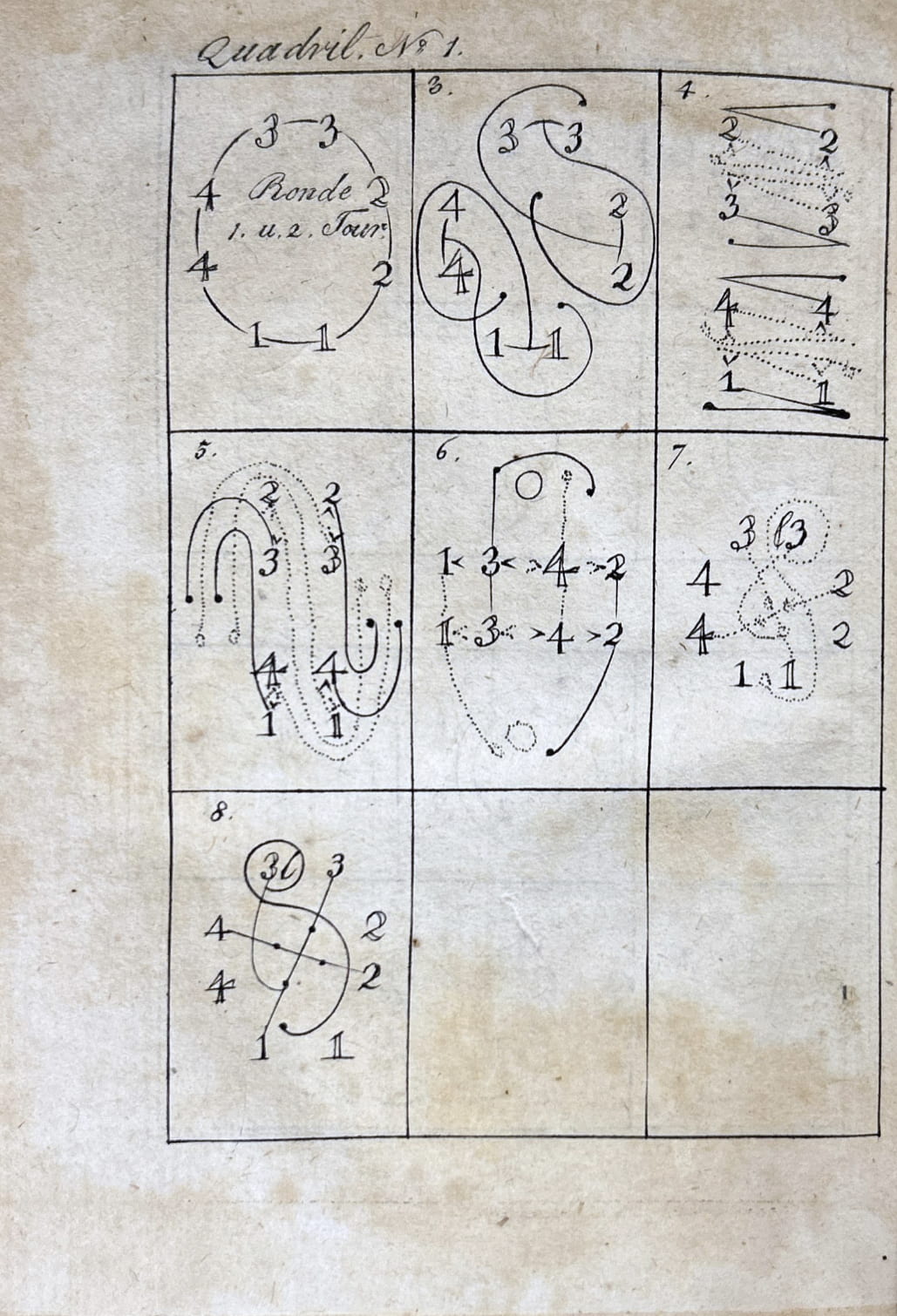

Taschenbuch zum geselligen Vergnügen 1803: The volume features, here, a dance instruction for the Quadrille No. 1.

Despite the disperse nature of the German political entity, held up loosely by the end of the Holy Roman Empire in the 18th Century and by the German Confederation throughout much of the early 19th century, there were still ‘national’ phenomena, namely that springing from the German-speaking Aufklärung, or Enlightenment. This philosophical, political, and cultural force spread from the onset of the 18th century well into the 1770s, especially among the educated, German upper-middle class. Print media was thought to be its chief disseminator. The essays, histories, pieces of literary criticism, and accounts of new scientific discoveries represented a continued propagation of the Enlightenment and its ideals across all literate strata of German society. The lighter literature, riddles, dances, and games also embodied the spirit of Gemütlichkeit (congeniality) so closely identified with the German middle class of the period. Indeed, many volumes in the Taschenbücher collection, like the one featured below, preach “geselligen Vergnügen” or sociable entertainment: they bill themselves as social, rather than solitary objects, quite unlike the books of our time.

Despite the fact that large scale industrialization did not occur in Germany until the 1830s, the 18th century marked a sea-change in and rapid proliferation of the literary use of the German language. Until as late as 1700, there were more books published in German-speaking territories in Latin than there were in German. But over the course of the following century, the literary landscape would change wildly: while in 1700 there were only an estimated 80,000 literate Germans, by 1800 there were as many as 550,000. There came to be, as a result, a flourishing of German publishing: where in 1740 only 750 new titles were published in German-speaking territories annually, approximately 8000 new titles were published annually in the 1780s and 90s. Not only was there a rise in literacy, there was also a rise in literary appetite, and the Taschenbücher were designed to satisfy this new craving.