The extreme violence and war-like imagery of Prudentius’ Psychomachia can be quite startling—and even shocking—for many, especially for those who associate the Christian scripture on which this text is based with the loving and peaceful preaching of Jesus. However, quite a few aspects of the Psychomachia are directly reminiscent of Christian scripture—most closely, the Book of Revelation in the New Testament. Prudentius describes an epic battle between the forces of good and evil, complete with war-like personifications of virtues and vices as female warriors. Revelation’s “John” also creates a stark dichotomy between the forces of good and evil in the form of militarized embodiments of concepts and ideas. In Chapter 7, John describes the sight of four horses and their four riders:

“I looked, and there was a white horse! Its rider had a bow; a crown was given to him, and he came out conquering and to conquer. When he opened the second seal, I heard the second living creature call out, “Come!” And out came another horse, bright red; its rider was permitted to take peace from the earth, so that people would slaughter one another… When he opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature call out, “Come!” I looked and there was a pale green horse! Its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed with him; they were given authority over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword, famine, and pestilence, and by the wild animals of the earth” [Revelation 6:2-7].

These riders, much like Prudentius’ vices, are human incarnations of evils: that is, conquest, war, famine, and death, respectively. Contrastingly, John also describes the human incarnation of the counterpoints of these evils: “I saw heaven standing open and there before me was a white horse, whose rider is called Faithful and True. With justice he judges and wages war. His eyes are like blazing fire, and on his head are many crowns. He has a name written on him that no one knows but he himself. He is dressed in a robe dipped in blood, and his name is the Word of God. The armies of heaven were following him, riding on white horses and dressed in fine linen, white and clean” [Revelation 19:11-14].

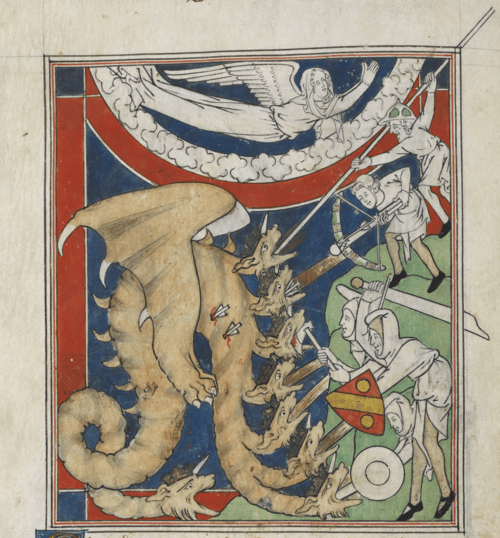

In another parallel, in both texts the “good and holy” gather to battle against the “evil and godless.” In Prudentius’ text, the virtues of the soul come together to make war against the vices of the soul—in Revelation, the battle is for humanity as a whole, as the “dragon” who represents Satan and his followers battle against the followers of Christ: “The dragon was angry with the woman, and went off to make war on the rest of her children, those who keep the commandments of God and hold the testimony of Jesus” [Revelation 12:17].

The final parallel worth noting is the feminization of virtues and vices in both pieces. In the Psychomachia, all virtues and vices are presented in the forms of women; in Revelation, although only several characters are female, they are still quite notable. The first is the “A woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. She was pregnant and was crying out in birth pangs, in the agony of giving birth” [Revelation 12:1-2]. While there is much debate on who exactly this woman represents, many agree that she is the personification of Israel and all its goodness, much like how the virtues of Prudentius represent the goodness of God’s children.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is the “Whore of Babylon,” described in Chapter 17: “The woman was dressed in purple and scarlet, and was glittering with gold, precious stones and pearls. She held a golden cup in her hand, filled with abominable things and the filth of her adulteries… I saw that the woman was drunk with the blood of God’s holy people, the blood of those who bore testimony to Jesus” [Revelation 17:4-6]. When considering the images of the excess of the woman’s clothing, jewelry and drunkenness, one cannot help but be reminded of the figure of Indulgence in the Psychomachia, living only “for pleasure” in “wantonness,” and basking in the allure of her excessive lifestyle.

It is evident that while Prudentius’ work is highly influenced Greco-Roman tradition, it is also heavily steeped in the language and imagery of Christian scripture. As such, many of the aspects of the Psychomachia that we find “uncharacteristic” of the original message of Christianity are, in truth, drawing directly from the holy text itself.

Notes:

- I used the New Revised Standard Version of the New Testament for all quotes.