by Kaedy Puckett, Clare Kemmerer, Dannie Griggs, and Maya Ordonez

Faith No More?

By Kaedy Puckett

One cannot help but wonder about the course of Matthew and St. Andrews’ faith if the narrative of Andreas had an alternate ending. Had Andreas failed in his mission to rescue Matthew from the Mermedonians, would either or both of them have lost their faith in God? After all, God had assured Matthew of his impending rescue, and Andrew of his success. God also intervened in various ways throughout Andrew’s journey to Mermedonia to help ensure his success, yet he allowed Andrew to be tortured for three days prior to rescuing him. Had Andrew’s mission been devoid of God’s intervention and had Matthew fallen prey to the cannibalistic Mermedonians, how would this story change the role of the witness for Andrew, Matthew, and the reader? If Andreas, which serves as a microcosm for Christianity, had ended tragically, would this text have been included in the manuscripts of monks and read for years to come as a religious text of witness?

The following elegy is written for the death of Faith, after St. Andrew and Matthew lose theirs in the reimagined, alternate ending of Andreas where St. Andrew fails to rescue Matthew and both suffer immensely before being consumed by the Mermedonians:

Faith-

How long, the life or lives you’ve lived,

now gone, and left forsaken

Your absence cuts a chasm deep,

in darkness overtaken.

With grasp so tight and strength severe-

this heart that held you dearly-

Is sadness filled and in despair,

resigns itself austerely.

For years and years with me you stayed

and shined your light so brightly.

Each day arose we with the sun;

your comfort sheathed me nightly.

When to the sky my glares directed,

and clouds drift by reminding,

of kindness great, your mighty deeds

that kept my heart in binding,

I shall not weep a single tear

nor shall I deign to pardon.

Abandonment at time of need,

which forced my heart to harden.

But find I solace in the the thought;

you shall remain forever,

In hearts of those whose purest souls

to God’s grace do endeavor.

Poetic translations of Andreas excerpts

Clare Kemmerer; Images courtesy of Dannie Griggs

He saw flowering groves covered with blossoms

Where he had previously shed his blood.

(c. line 1444, Andreas)

What I know of new flowers is their fierce fragility:

Small naked shoots fighting black earth & crows & early frost,

White-yellow faces bursting forth to hide from the moon.

At night I thought I saw their faces bleed, as if

God had come down and broken their noses in his grief,

As if he missed the taste of His blood and wanted the blossoms

To share his chalice. & in my cell I missed blood too, &

Pulled water from the sky & skin from my palms so that

I could feel drinking again in the roots of my feet.

Father of angels, I wish to ask of you, Creator of light and life:

Why do you forsake me?

(c. line 1410, Andreas)

I am always thinking about the way that Christ died, the intimate

awfulness of it, the way his lungs began to collapse beneath the weight

of his shoulders, the way his hands began to pull at the tendons, the way

that doubt began to form at his edges like dirt under fingernails.

Or how he must have watched his mother cry–maybe saw her

faint at his feet like the stories say, or just saw her face close

slowly off as she realized he was dying and began to, just slightly,

separate herself from him. But mostly I think about the many breaks

in my own skin, & how even God only had to suffer

for a single day before his father took him home. It’s like this: I want

to believe that we are the same, but I know that he had Someone waiting

for him & now I’m not so sure that I do. & I know that to say that is

to sin, & that he can hear us in our minds, & that we should always

be grateful but, just for right now, I am feeling at the edges of my

own flesh, where it is flayed and beginning to give, where the dirt-doubt

clutters. There is so little of us beyond our bodies. I have spoken

the tongue of the world that will come, but now that tongue is

scream-bitten & that mouth stopped by blood & I am thinking that

if I had a father he would come & take me from this poor cradle.

Nor are the highways across the cold water familiar to me.

(c. line 201, Andreas)

When I am teaching the air is full of voices & questions

& it becomes hard to distinguish one from the other:

the ontological prodding, the childish whine, the voice of God.

& his words which spoke of water and flesh and distance

and wonder and death seemed so far from me as to be a

fable, & I thought for a minute the voice had come from

a child or myself. But I heard it & so soon I will begin to walk,

& if I begin to walk a little faster it will be because of angels,

& if that walk becomes a sail it will be because of the the sea,

which is to say, a God made of salt. When I come

back to my classes I will be late & I will be wounded &

perhaps the children will run from what I have become, but

I will bring with me new brothers & we will be always

together on the waves, stepping with our too-fast strides, sailing

on our too-rough way. & perhaps as some small fact God will

come back as a flower or a dream or a friend, & we will walk &

work beside one another, & I will be born to myself again.

The Sun as the Eyes of God

Maya Ordonez

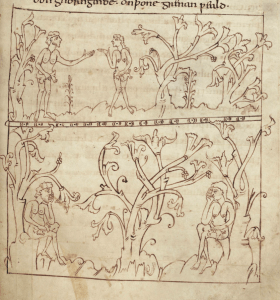

Could the Sun be God’s eyes? Or even God? Just as the Sun’s warmth and radiance are omnipresent, God is always watching over the Earth. All life is either directly via photosynthesis or indirectly, due to Earth’s proximity to the Sun allowing for the existence of liquid water, dependent on the Sun. Both God and the Sun are “Author[s] of light and life” (Andreas, line 386). Trees, plants, and reach toward the heavens, towards the Sun. The idea about the Sun having some sort of relation to God first surfaced in viewing the Junius manuscript. The leaves on the plants featured in the image in the Fall of Adam and Eve seemed to resemble hands: hands that were reaching skyward. In the upper image, one of the leaves next to Eve almost appears that it’s pointing at Adam and Eve, ridiculing them. Only the leaves near Adam and Eve in the time of sin are not not directed upwards, towards the Sun. This could possibly signify the darkness that Adam and Eve have become encapsulated by, due to their sin. They have fallen out of the light of God. The only reason that plants turn away from the sky is if the sun is not present. Since God was unaware of Eve and Adam’s sinful act, the plants are out of the sight of God; they are not within the Sun’s rays.

Fall of Adam and Eve – Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Junius 11, p. 39

In Andreas, man’s eyes are related to “His head’s sunlike orbs” (Andreas, line 49). This comparison draws the connection between the Sun and mans’ eyes revealing that the Sun is, in a sense, a sort of eye. It’s location and all-pervasiveness are equal to that of God’s. In the dark, although one may be out of the direct sight of God, his vision can still reach those in this position. Likewise, during the night, although the Sun’s rays do not penetrate the Earth directly, the light of the Moon is provided by the Sun. Although we may not feel the light of God or the Sun in the darkness provided by their absence their presence is irrefutable.

“Just then the sun, brightest of beacons, came in its morning radiance, a holy thing, hastening out of the darkness across the deep; heaven’s candle shone over the water of ocean.” (Andreas, line 240-243)

This quote also reveals the connection between the Sun and God. The Sun brings light into the world just as God’s sight does. God’s vision directs those who are lost and unsure; the sun is the “brightest beacon” within the darkness.

Images