One of the most fascinating aspects of Genesis B is its numerous departures from the Vulgate Bible, most notably in the depiction of Eve. The poem’s recounting of the first Biblical story, the fall of humanity from Eden, calls into question notions of culpability and agency in the Bible. Did Adam and Eve have agency, and by extension, do their descendants, humans, have agency in the Judeo-Christian universe?

When Adam and Eve are first created, they are shaped with childlike innocence, unable to conceive of the world around them. “They did not know how to do or commit sin,” as the poem recounts, “but the burning love of the Lord was in the breast of both” (Genesis B, page 15). Thus, Adam and Eve’s lives are restricted to faith in and obedience to God, who forbids them to eat of one tree in the garden (“renounce that one tree, guard yourselves against the fruit” [Genesis B, page 19]), which the poem describes as the tree of knowledge: “whatever person tasted of what grew on that tree, must know how good and evil turn in this world” (Genesis B, page 39). These descriptions of Adam and Eve’s ignorance further entrench this question of agency–without awareness of sin or moral judgement, can they truly make independent decisions? Was it even possible that they might resist temptation?

Satan, taking the form of a snake, wishes to trick Adam and Eve into disobeying God’s order, yet this trial is complicated by the aforementioned circumstances of Adam and Eve. Satan’s trickery is the first instance of lying they have encountered, and with no knowledge of good or evil, it is difficult to conceive of such a concept. Even though Adam resists Satan’s trickery, he says “I do not know, however, if you have come deceitfully with hidden intentions” (Genesis B, page 43), implying that he is still unable to differentiate between lies and truth.

While Adam’s successful resistance may imply agency does exist, there are yet notions which cast doubt- such as the differences between the temptations he and Eve encounter from Satan, as well as in both his and Eve’s creation. Initially, Satan’s attempts to convince Adam focus on individual benefits— “your ability and skill and your mental capacity would grow greater, and your body much more radiant, your shape more beautiful” (Genesis B, page 41). However, his words to Eve claim foremost that he is a messenger from God. Even when Satan claims Eve will benefit, he contextualizes it within God’s approval- “your eyes will become so enlightened… and (you will) henceforth have His favor.” (Genesis B, page 45) While Satan tempts Adam claiming to be a messenger of God as well, his words are far more manipulative to Eve, convincing her that God will be angry if she does not cooperate- “lest you two…. become hateful to God your ruler… if you succeed… I will conceal before your master that Adam spoke… wicked words” (Genesis B, page 45)- thus approaching her with veiled threats, and implying that to eat of the fruit is redemptive rather than simply beneficial. These elements complicate Eve’s temptation by introducing notions of guilt (redeeming them for Adam’s refusal) and duty, whereas Adam was mostly bribed through the possibilities of his own gain, external to God’s wishes.

Furthermore, Eve’s creation differs from Adam’s. She was fashioned from his body, yet “the creator had designed a weaker mind for her.” (Genesis B, page 47) These deficiencies, intentionally and directly fashioned by God, complicate the matter of her agency- if she is less fit to resist temptation than Adam, can she be held responsible for failing? The poem emphasizes this element of deception. “She began to trust in (Satan’s) words…. accepted the belief that he had brought those commands from God,” (Genesis B, page 51) it reads, further elaborating that she had been “secretly led… astray,” and that Satan “eagerly interfered within the soul.” (Genesis B, page 47) This contextualization is interesting because Eve shoulders much of the blame for humanity’s fall, as she is the one who first disobeys God, and convinces Adam to follow suit. Yet, emphasizing this question of agency, portraying her as thoroughly deceived, calls her accountability into question.

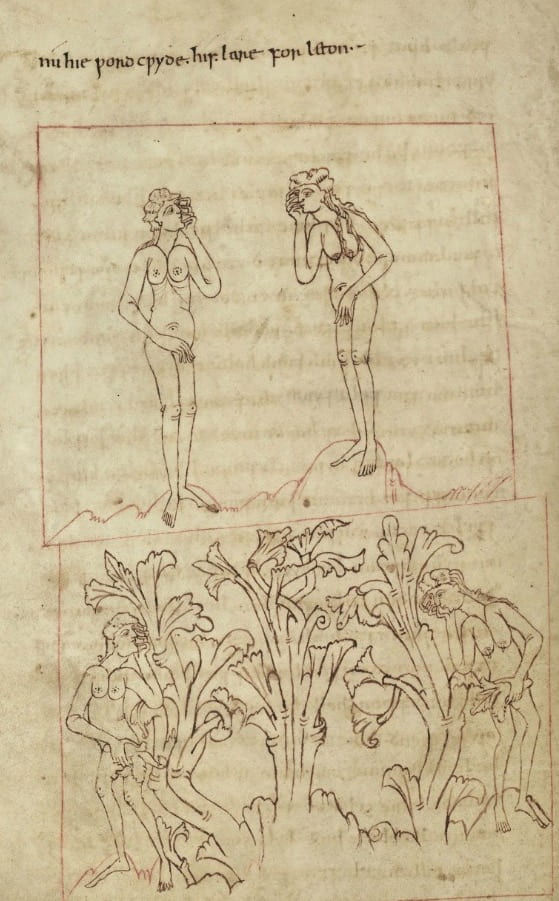

The treatment of Adam and Eve forms the foundation of the human condition as portrayed in the Bible- as aware of morality, yet cursed by the misdeeds of their ancestors. This guilt is particularly enforced upon women [“so must her heirs live afterwards” (Genesis B, 47)], as the descendants of Eve. This notion is further emphasized in the images accompanying the text.

The image depicts Adam and Eve covering their genitals in newly-learned shame, also interestingly hiding their faces- averting their eyes from their nakedness. Adam and Eve both attempt to avoid witnessing their own punishment. Yet, what is most interesting is their orientation to the viewer. While their hands fully cover their genitals from an observer’s view, the attempt to hide their faces is failed- Adam and Eve’s eyes and faces are still visible to the viewer. Thus, just as the text involves the descendants of Adam and Eve, the art equally implicates them. Not only do we bear witness to Adam and Eve’s fall, but on a meta-level, we are directly acknowledged in the art. In their failure to hide their faces, and inability to avoid witnessing the fall, the futility of escaping the original sin is reiterated for the observing audience.

This question of agency is then re-iterated for Adam and Eve’s descendants, the human race as a whole. If this sin is inherited, what agency persists? In the Judeo-Christian understanding, no surviving human is directly responsible for the fall, so why must they be held responsible? This seems to imply a lack of potential agency, yet, much of Judeo-Christian teaching focuses on analyzing moral choices and encouraging compliance with divine law. These contradictions belie deeper questions about autonomy and its interactions with morality. Can we have free will, and make free choices if we are ultimately shaped by experiences we cannot control? Can responsibility be fostered if we, much alike Eve, are not creatures of our own creation?

Source:

Anlezark, Daniel, ed. and trans. Old Testament Narratives. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011. (Genesis A and B, and Daniel)

I found it interesting when you wrote, “Not only do we bear witness to Adam and Eve’s fall, but on a meta-level, we are directly acknowledged in the art.” I am curious why it feels as if religious art, specifically during the medieval period and the renaissance, always has this meta feeling to it. Often we see the Madonna with child or a gathering of disciples at a table with at least one if not all of them turning their attention to the viewer. Why do so many artists try to focus the gaze of a religious figure on the person who is gazing back at them? I am curious if it has anything to do with a sort of religious guilt. I remember learning about many Catholic churches that were built during these periods and the gothic period as well that included many figures in the architecture that would look directly at a passerby and try to guilt them into attending services. Some of the figures would have looks of fear or be depicted as entering hell for not going into the church and I am curious if your earlier idea of autonomy is just completely out of the question when it comes to religions like the Catholic Church or stricter forms of Christianity. There has always been the argument of free will in religions like this, but it seems almost as if people are more often forced or guilted into doing something faith-related rather than entering out of guilt-free, willing conscious.