This two-part post set will pull out moments in the Old English Genesis where I found translation questions particularly pertinent. First, I will compare some residual effects the most proximate language of translation left on the Modern English versions of the Old English and Vulgate descriptions of the Flood, respectively, how the two poems look at the horror of the destruction. In this moment, the two versions are mostly similar, allowing a side-by-side evaluation of the alterations made. The same is not true of the second selection: the Old English dramatically dilates what is, in the Latin, a mere two-verse killing. In the more expansive, second post, I will read an opportunity to explore the effects and limitations of translation, whether that be translating experience into words or one language to another.

Diluvian Description

The flood, fierce under the heavens, completely covered the high mountains across the wide earth and on the sea lifted up the ark from the earth, and the noble family with it, which the Lord himself, our creator, had blessed when he sealed the ship. Then the most excellent craft rode widely under the clouds across the expanse of the sea, traveled with the cargo. The terror of the water could not violently buffet the wave-tossed ship, but holy God steered and saved them. The drowning flood stood fifteen human ell-measures deep over the mountains – that is an amazing fate!

And the flood was forty days upon the earth, and the waters increased, and lifted up the ark on high from the earth. For they overflowed exceedingly: and filled all on the face of the earth: and the ark was carried upon the waters. And the waters prevailed beyond measure upon the earth: and all the high mountains under the whole heaven were covered. The water was fifteen cubits higher than the mountains which it covered.

Speak these two paragraphs, aloud or in your head. How do they feel?

Do you find that they are saying the same thing?

If I presented these passages in the language from which they are most immediately translated, they would be nothing but strange, unfamiliar and unparseable. As it is, though the translations of Old English Genesis lines 1386-1399 (above) and of the Vulgate Genesis 7:17-20 (below) tell the same story, we may treat them as distinct poems in their own right, as they, in their respective ways, try to convey the enormity of the terror and the miracle of the Flood. The Vulgate accomplishes this by focusing on the activity of the waters. Looking at the subject of every verb in the passage, active and passive, the waters, aquae, and the flood, diluvium, are the sole actors. Every other thing is not in God’s hands, but at the whim of the pervasive flood. Though, naturally, the flood is God’s flood, in the moment of the disaster itself, God is removed from the action, and responsibility ceded to his Creation. I wonder to what extent we may read into this delegation of responsibility: to a degree, it mirrors the very beginning of Genesis, where God speaks (“Dixitque Deus : Fiat lux,”) and the world comes into being (“et facta est lux,” Gen 1:3) in two separate actions, the Divine Word separated from the Creation. In the same way, in Genesis 7, God creates the Flood, and then we have this passage, where Flood, not God, is the primary actor. Are we meant to read the Flood as now solely responsible for its own destruction and terror? Theologically, reading this as God stepping away and letting the Creation tick along as it will is…fraught. For purely literary purposes, though, God’s absence in these moments allows the sufferers – Noah and his family – to turn to God as succor, rather than from him, as the cause of their present situation.

Though the Old English starts out in the same manner, God steps in quickly – albeit with the past action of blessing Noah’s family – and then, once reaffirmed in its blessed and sealed state, the ark is capable of mastering the flood and assuming responsibility for its contents. Rather than cede all control of the story to the waters, the Old English creates the atmosphere of overwhelming deluge with descriptions: the flood is “fierce” and “drowning,” we see the sea’s “expanse” and “terror,” and when it is the actor, it covers “completely” and buffets “violently.” There is an undercurrent of reassurance for the reader, that “our creator” would not let the ship be harmed. That though the storm is terrible – and must be constantly reaffirmed as such – that terror can coexist with a divine peace and safety for those inside the ark. In this way, the Old English goes further than the Latin, almost putting God and the Flood in direct opposition, battling over the ark’s safety or destruction. That said, I wonder whether this struggle, between God-safe ship and violent storm, is the defining mode of the poem. Isaiah pointed out the frank jollity of the concluding phrase, and it does not seem, at least to me, to come out of the blue. Rather, the terror of the flood and the soon-emphasized safety of the ark build to the concluding moment where awe at the miracle of the complete destruction and soon-to-be renewal overwhelms any fear or sorrow or any other response to the Flood.

There is a broader argument to be made here, about Old English seafarers wandering the vast ocean expanse, and customary cultural attitudes towards such, but for now, let it suffice to hold up the Old English next to the Latin, and assess the verses’ emotional tenor, parse-able at the level of diction but legible even in internal rhythm, and stand in awe, like Noah looking at the flood, at the encrypted lingual heritage of the respective translations.

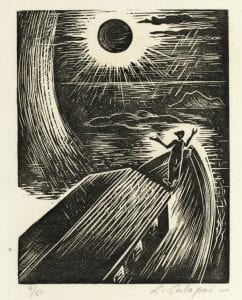

Noah – The Ark (1946) by Letterio Calapai

From the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Wood engraving in black on cream Japanese paper.

Old English text and translation from Anlezark, Daniel, ed. and trans. Old Testament Narratives. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Latin text and translation from The Holy Bible, Douay-Rheims Version. Ed. Bishop Richard Challoner. John Murphy Company. Baltimore, MA: Tan Books, 1971. From http://www.drbo.org/, ed. Paul B. Mann