Note: Before reading, I just wanted to write that some of the images seen here in this two-part post are quite graphic and may cause emotional distress. I know the topic is already quite brutal and distressing, but I do not want to cause undue harm because my work is work for class. So I urge you to use your judgment and do not read this post if extreme violence, especially towards women and Jewish people, will be too much for you to read and see.

There is an idea of false consciousness (a way of thinking that prevents a person from truly understanding what is happening to them) present in the viewing of photographs. Images of extreme pain and suffering often invoke a level of sympathy, an understandable reaction from any person. However, this reaction instead invokes a sense of familiarity alongside this sympathy, where this feeling of horror and upset links us to the other person as they suffer: “The imaginary proximity to the suffering inflicted on others that is granted by images suggests a link between the far-away sufferers—seen close-up on the television screen—and the privileged viewer that is simply untrue, that is yet one more mystification of our real relations to power” (RPO, 102).

This sympathy is quite—and for the lack of a better word—useless. Feeling bad that someone is suffering and relating to a person because of it is not going to stop the violence from occurring. This reaction is all created because this voyeuristic need to watch and see, which creates an invisible bond that relates the suffering to the spectator, helping the viewer not feel bad for their witnessing. This is perhaps the false consciousness that Sontag tries to get towards, and she shows how this problem is also not entirely inherent to images of suffering:

“Images have been reproached for being a way of watching suffering at a distance, as if there were some other way of watching. But watching up close—without the mediation of an image—is still just watching. Some of the reproaches made against images of atrocity are not different from characterizations of sight itself. Sight is effortless; sight requires spatial distance; sight can be turned off…” (117-8).

Most of Regarding the Pain of Others is focused on photographs, an understandable discussion as most of this discourse focuses on the invention of photography and its uses in photojournalism. However, Sontag also goes on to show how art, although not photographic, can still evoke and portray the same suffering seen in images, as exhibited with Goya’s etchings. With this in mind, Christian tradition would have been an interesting point to the argument, one that shows this strong emotional upheaval via art, as all images of the crucifixion or of martyrs are usually artistic renditions (carved crosses, metal rosaries, Renaissance paintings of the Crucifixion, etc.).

However, where I thought Sontag would do so, she doesn’t and instead gives a simple seven pages (40-1, 79-81, 98-9) to the topic. Keeping this idea of the false consciousness in mind, I want to make the claim that images of the Crucifixion or just simply the cross can help bridge this muddy middle ground between the spectator and the sufferer. In other words, a full identification via such icons, where the Christian narrative presents more than one meaning for images of suffering that could lead to further reflection of oneself.

The predominant image of suffering in Christian liturgy is the image of Jesus on the cross. The narratives surrounding this are immense. Because of this, there are many ways that the story can be crafted, similar to how Sontag says many stories can be crafted from one static image. However, it always aids in helping the witness to understand God’s perspective on human suffering, to understand a divine nature through the cross. To attempt to maintain the kind of sentimental, aesthetic or sympathetic distance from the cross that some spectators attempt to maintain from images of pain, violence and terror is to misunderstand the meaning of the symbol and its place. To gaze at the cross and go “Truly, humans are cruel,” similar to how one can read a newspaper and look at its accompanying image and tsk, seems unsatisfactory of a response to the cross. In other words, most Christian discourses on the cross and its relationship to human suffering have built within them a demand of identification that is different from the discourses surrounding images of suffering more generally. To my understanding, this identification with the suffering of the Crucifixion and the cross is not so much removed from the question as much as it is assigned a new meaning. The question now has changed from “Should the viewer identify themselves with the suffering on the cross?” to “In what ways can the viewer identify themselves with the suffering on the cross?”

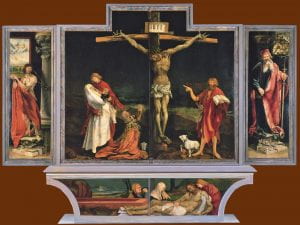

Images of the crucifixion themselves can assist in this reworking of the cross and the identification associated with it. Matthias Grunewald’s depiction of the crucifixion from the Isenheim Altarpiece is the most stark and grotesque representation of this image in Christian art. Jesus’s body is covered in streams of blood; his bones and muscles show prominently; his entire body is covered with plague-like sores; his feet are mangled; his hands are contorted into eternal anguish; his head hands in entire defeat, giving into death. Although viewers may look upon this figure as the epitome of Christian glorification of suffering and humiliation, the intention of the piece was to be made for a chapel hospital. The piece’s intention was to help the ill and dying of the plague and ergotism connect to Jesus’ suffering with their own and gain courage in their journey, since Jesus understood their misery and knew how to alleviate it. So even in severe Christian tradition, there is still this idea that the cross can help one fully identify with the suffering and to understand this plight in a new way.

Susan Sontag. Regarding the Pain of Others (New York, Ny: Picador, 2003).

Header: Nikolaus Hagenauer and Matthias Grünewald. 1512-16. Isenheim Altarpiece. Oil on wood, 298.45 cm x 327.66 cm (117.5 in x 129 in). Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2017/jan/05/crucifixion-glasgow-theology-students-violent-brutal-images-death-paintings.

Image 1: Nikolaus Hagenauer and Matthias Grünewald. 1512-16. Isenheim Altarpiece. Oil on wood, 298.45 cm x 327.66 cm (117.5 in x 129 in). Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, France. https://www.artbible.info/art/isenheim-altar.html.