Note: Before reading, I just wanted to write that some of the images seen here in this two-part post are quite graphic and may cause emotional distress. I know the topic is already quite brutal and distressing, but I do not want to cause undue harm because my work is work for class. So I urge you to use your judgment and do not read this post if extreme violence, especially towards women and Jewish people, will be too much for you to read and see.

Relying on the crucifixion as a somewhat thematic foil, artists outside of Christian theology and its tradition have used the cross as a framework for a wide range of critiques. Marc Chagall’s crucifixion paintings, for example, created during the rise of the Nazis in Europe, depict Jesus as a Jewish martyr and contain explicit violence to Russian and Nazi violence towards Jewish communities. In White Crucifixion especially, Chagall depicts Jesus wrapped in a Jewish prayer shawl, the “angels” surrounding the cross are reminiscent of biblical patriarchs and matriarchs and the entire background is filled with images from the Jewish liturgical world. This image quite blatantly tries to draw attention to Jewish suffering in a visual symbol that Christian spectators were familiar with, in hopes that they would respond accordingly.

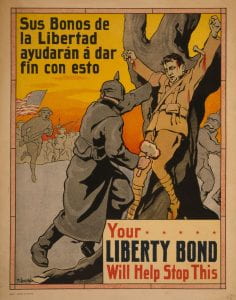

On a similar thread, during World War I, Fernando Amorsolo, a Filippino artist, made Liberty bond posters that depicted a German soldier nailing an American soldier to a tree, with the American soldier’s arms stretched out to his sides. The title, written in Spanish and English, says “Your Liberty Bond will help stop this/Sus bonos de la libertad ayudarán á dar fin con esto,” appealing to a large demographic that was Catholic to get them to pay taxes to support the Allied soldiers win the war.

On a similar thread, during World War I, Fernando Amorsolo, a Filippino artist, made Liberty bond posters that depicted a German soldier nailing an American soldier to a tree, with the American soldier’s arms stretched out to his sides. The title, written in Spanish and English, says “Your Liberty Bond will help stop this/Sus bonos de la libertad ayudarán á dar fin con esto,” appealing to a large demographic that was Catholic to get them to pay taxes to support the Allied soldiers win the war.

Sue Coe also uses the Crucifixion in order to make several charged political and social justice statements. The most controversial and quite blatant uses of the cross is seen in her piece Woman Walks into a Bar – Is Raped by Four Men on the Pool Table – While 20 Watch. The piece addresses the 1983 New Bedford sexual assault case where the charges were ultimately dropped because all the witnesses testified to seeing nothing happen. I wanted to bring this piece up because 1. it engages the use of the cross in ways that I am talking about but also 2. it also actively includes the spectator into the piece. In the piece, there are not 20 other people depicted; what does this mean? This then means the people outside the piece, the spectators, have become part of the 20. The spectators are thereby also guilty of witnessing this suffering and not doing anything (aka looking at the piece and then walking away, going home, living their lives). Coe through this calling forth the problematic issue of spectatorship and asks the uncomfortable question, “What is your role in this? Why are you witnessing this suffering?”

My personal favorite is a more inspiring and optimistic–or as much of this as an image of the Crucifixion can be–rendition known as the Wales Window for Alabama. In 1963, four young Black girls were killed and almost two dozen others were injured in a Ku Klux Klan bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The outrage spread globally and reached Wales, where John Petts, a stained-glass artist, offered his services to create and install a replacement window for the church. Petts’ depiction is recognized as one of the Civil Rights Movement’s most iconic works of art and is displayed at the front of the rebuilt church. The window is another beautiful example of identification seen through art. I highly recommend reading the Birmingham Times‘s commemorative article on the window.

There are many more interpretations–and interestingly, many more interpretations that were censored or entirely changed for different audiences, like differing manga panels from Full Metal Alchemist in the Japanese and American editions. (The reasoning behind this was that the cross in Japan is understood to be a secular symbol of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki while in the U.S., as we know, has a entirely different meaning and they didn’t want the panel to cause discourse about blasphemy). It goes to show the ways that one symbol of suffering can hold a multitude of meanings, both good and bad, in the world.

Header: Graham Sutherland. 1947. Crucifixion. Oil paint on board, 1168 × 1472 × 83 mm. Tate Museum, United Kingdom.