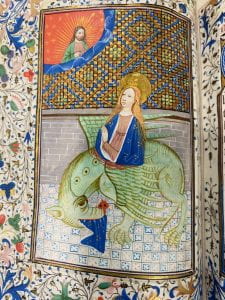

St. Margaret emerging from the dragon unscathed (Image from Newberry Library MS 35, Book of hours, use of Salisbury, 1455 https://www.newberry.org/english-medieval-book-hours)

There is much to be shocked by in the Old English life of Saint Margaret: gruesome depictions of beheadings, beatings, and sexual threats are interpolated with Margaret’s miraculous exorcism and escape from the stomach of a dragon. Yet the first time I read Margaret’s hagiography, I found myself most surprised not by the tale’s violence or its inclusion of magical creatures, but by Margaret’s ability to turn her immersion into a vat of boiling water into a self-officiated baptism. While self-baptism is an oddity in of itself, I was particularly amazed that a woman’s self-baptism was enshrined as legitimate in a faith-promoting narrative, given that the majority of contemporary Christian women are still barred from receiving the officiating in baptisms and other rites, despite the ordination of women in many Protestant sects. I distinctly remember learning when I was fourteen that Kate Kelly, a prominent Mormon feminist, had been excommunicated from my faith tradition for founding the organization Ordain Women. The denial of official baptismal power to women is present in much larger Christian churches as well; in 2007, in response to the actions of groups like Roman Catholic Women Priests, Pope Benedict XVI authorized a decree of automatic excommunication for anyone attempting to ordain women or receive ordination as a woman. But, although ordination is not at stake in the life of St. Margaret, it is clear that her declaration “that this water may be for me a healing and an enlightening and a bath of baptism” still carries the weight of an officially sanctioned baptism in the narrative. As soon as her prayer concludes, her limbs are freed and a dove descends from the heavens bearing a crown in its mouth, like the Holy Spirit descending in the form of a dove after Jesus’ baptism in Luke 3:21-22.

What is this divinely-approved, self-performed, feminine baptism doing in an Old English manuscript? Does Margaret’s spiritual prowess exist in spite of, or because of her womanhood? How did other women, both in the narrative and real life, respond to Margaret’s baptism? What are the specific gendered dimensions of this form of torture-turned-resistance? I hope to illuminate these questions first by providing background on the meaning of Margaret’s baptism itself, and then by reading The Old English Life of Saint Margaret alongside the earlier and exceedingly similar story of Thecla from the apocryphal Acts of Paul. Thecla is another virginal, self-baptized, and tortured female saint, who is thrice mentioned in Margaret’s hagiography as an example; the comparison of their lives reveals some of the common issues at play in women’s self-baptism.

The Origin & Legacy of St. Margaret’s Baptism

First: how did Margaret’s baptism make it into this text? In an article analyzing the Mombritius version of the early medieval Latin Passio S. Margaretae, upon which our Old English text (and other vernacular versions) are based, Marie Schilling Grogan notes that although Margaret’s immersion is clearly a baptism in earlier versions, the active declaration of the prayer “baptiza me in nomine Patris, et Filii et Spiritus Sancti” is introduced in the Mombritius version, but removed in some later versions. Though this formula conforms to Western baptisimal liturgy, it exists uneasily among a fluid conception of what legitimate baptism could consist of; there was a “wide variety in local practices” in both Eastern and Western Christianity of the time. Grogan notes that the removal of Margaret’s self-baptism “coincides in some versions with the insertion of information earlier in the story that she was baptized as a child,” demonstrating a persistent “concern over the question of formal initiation and the possibility that there are other ways of attaining the grace of baptism.”

Despite the debate over self-baptism, Margaret’s power to turn bodily torture into salvation served as a powerful material comfort to medieval women struggling through the pains of pregnancy and birth. In an article investigating the “transcorporeal landscape” of Margaret’s life, Megan Gregory notes the enmeshment of Margaret’s body with her cult of female followers, who brought manuscripts relating her corporeal acts to the birthing room to provide comfort. Margaret insists in the narrative that the power of her acts is passed on through words, asking God to hear her prayer that “whoever writes out my passion or hears it read may from that time have his sins blotted out.” For Gregory, “Margaret is there communing with the other women in the birthing room” through the presence of her manuscripts. Grogan argues that this strange communion of a virgin with women in the throes of labor can be explained through Margaret’s orchestration of her own baptism. Medieval women feared having a stillborn baby who did not live to receive baptism and therefore salvation. Grogan suggests that perhaps Margaret’s performance of saving rituals provided them the hope of a non-institutional salvation: “When brought to the woman in labor…[Margaret’s life] would offer even the illiterate the comfort of the presence and promise of the baptismal words, spoken in the text by a woman, not a priest…The legend of Saint Margaret does not (and could not overtly) promise eternal salvation for infants who died before they were baptized, but it offered that hope.” This enduring cultural power clearly consists in Margaret’s straddling of institutional challenge and divine approval. In its uniquely feminine, corporeal, and reflexive form, Margaret’s baptism materially binds her through her manuscripts to generations of mothers whose worry over their stillborn children’s salvation could not be satisfied by official church doctrine. Yet, the appearance of a dove signifying God’s approval also allows the faithful to view this performance of female power as a legitimately sanctioned act.

Comparisons with Thecla (and her baptism in a pit of vicious seals!)

Saint Thecla in the water with sea creatures, Catedral de Tarragona

Although Margaret’s form of baptism challenges ritual gender boundaries, it is not entirely unique. In The Old English Life of Saint Margaret, a first-century female saint by the name of Thecla is raised as an exemplary figure for Margaret, twice by the narrator and once by the voice of God at Margaret’s death. Part of the apocryphal Acts of Paul, Thecla’s story shares obvious narrative similarities with Margaret’s, not least of which is the conversion of a violent threat into a self-performed baptism (which for Thecla occurs in a pit full of seals!). Though both texts promote women who claim their own salvation in the face of sexual violence, Margaret’s hagiography portrays her power as unique among women, while Thecla’s situates her within a complex matrix of female protectors, accusers, and participants. This ultimately creates differing narratives about the individual saint’s connection to women’s power and community in general.

Though I assume familiarity with Margaret’s life in this post, a brief summary of Thecla’s is in order (although it is brief and worth reading in full). Thecla, a seventeen-year-old virgin in Iconium, is betrothed to Thamyris until she hears the apostle Paul expounding upon “the discourses of virginity” (7) and abandons her engagement to follow Paul, becoming “chained to him by affection” (19). Thamyris is enraged at the loss of his fiancée, and demands a tribunal that leaves Paul scourged and expelled from the city. Thecla is stripped and set to be burned at the stake at the request of her own mother, but is miraculously saved by a rainstorm. She escapes and finds Paul, who refuses her request of official baptism, saying “be patient; you shall receive the water” (25). A nobleman named Alexander then tries to rape Thecla, and she fights him off, tearing off his cloak in the process. For this crime, Thecla is condemned to be eaten by wild beasts, but in order to preserve her virginity until the date of her execution, she is entrusted to the care of a rich woman named Queen Tryphaena. When Thecla is finally thrown to the beasts, a lioness defends her against the male animal attackers. When her female defender perishes, Thecla throws herself into a pit of water filled with seals, crying: “In the name of Jesus Christ I baptize myself on my last day” (34). The seals die in a flash of lightning and Thecla is hidden by a cloud of fire. Alexander again fails to torture Thecla when the women of the arena hypnotize the next round of beasts with perfume. Thecla is released, finds Paul, converts her mother, and lives as an ascetic to the old age of seventy-two.

From the outset, Thecla’s story introduces secondary female characters who forcibly enact their own power on her body. She, like Margaret, is imprisoned and tortured for both her expression of Christian faith and her refusal to satisfy male sexual desire. While the threat to Margaret’s virginity is enacted solely by the male prefect Olibrius, it is Thecla’s own mother, Theoclia, who demands the harshest of sentences for her daughter’s sexual unavailabity, crying: “‘Burn the wicked one; burn her who will not marry in the midst of the theatre, that all the women who have been taught by this man may be afraid’” (20). Thecla’s narrative thus reveals a concern with the way women enforce systems of sexual and ideological control amongst themselves. Theoclia’s incitement of violence against her daughter is driven by her wish to publicly re-enforce the necessity of heterosexual marriage on other women, even at the cost of her daughter’s life: “all the women” who have accepted Christian chastity must be made afraid, at the demand of a women and through violence against another woman.

In contrast, the female objectors to Margaret’s maintenance of virginity are driven not by a genuine ideological objection to chastity, but by visceral sorrow at the torture Margaret endures. Their communal declaration forms the only instance in the text where women other than Margaret speak:

“And all the women who stood there wept bitterly because of the blood and said, ‘O Margaret, truly we all feel sorry for you, for we see you naked and your body being tormented. This prefect is a very angry man and he wishes to destroy you and to blot out the memory of you from the earth. Believe in him and you will live”’ (9).

Here, the women witnessing Margaret’s torture play a unified narrative role: their visible emotion and pleas for Margaret to submit emphasize the gruesome gravity and public nature of her torture. While the women’s pleas are sympathetic, the fact that “all the women” recommend Margaret’s submission, while she alone resists, serves to position the saint as a uniquely strong woman in opposition to the default weak woman. Margaret angrily dismisses these pleas, saying: “O, you evil counsellors! Go to your houses, women, and to your work, men!” (9). Here, her dismissal of the onlookers accompanies their reassignment to traditional gendered domains, emphasizing how Margaret’s resistance is a departure from the normal state of gendered activity; it can neither be witnessed nor halted by a mass of normal women. Margaret’s feminine uniqueness is further emphasized when she vanquishes the devil in prison and he says: “I have continually seized many a righteous man and fought with him and none could defeat me…Yet now I have been destroyed by a young girl” (15). Margaret’s womanhood adds to the devil’s sense of surprise at his defeat–this is clearly a narrative in which a woman holding such great power is surprising. It is the nature of hagiography to portray spectacular events, but the gendered contrast of Margaret’s powerful dedication to virginity with other women’s weakness foregrounds a narrative of saintly singularity. When Margaret finally performs her own baptism, there is the sense that she is uniquely in control of the ordinance. It is hard to imagine that any other woman in The Old English Life of Saint Margaret has a significant influence on her declaration “Lord God Almighty, you who dwell in the heavens, grant to me that this water may be for me a healing and an enlightening and a bath of baptism, so that it may cleanse me for the eternal life and may cast all my sins away from me and bring me to salvation in your glory” (18). In this narrative, the climatic female self-baptism represents a performance of a kind of power that is not possible for any other woman, except through the reference to Thecla.

However, Thecla’s story continues to afford varying levels and forms of power to women characters even after the aforementioned scene with Theoclia. When Thecla is condemned to the beasts for resisting Alexander’s rape, the narrator includes the fact that “The women of the city cried out before the tribunal, ‘Evil judgement! impious judgement!’” (27). In some ways, the mass of women here plays a similar role to the women weeping at Margaret’s torture: their emotion emphasizes the injustice of the scene. However, their opinion reinforces the immorality of sexual violence, rather than suggesting submission to it out of ease. In this way, the “women of the city” form a counterpoint to Theoclia’s enforcement of heterosexual order; the narrative grants differing roles to different women in the imposition of or resistance to male control. Next, while waiting to be thrown to the beasts, Thecla receives support from a rich woman named Queen Tryphaena, who “took her under protection and had her for a consolation” (27). The relationship here is mutually beneficial; Tryphaena protects Thecla’s purity, while Thecla “consoles” Tryphaena and intercedes on behalf of her dead daughter’s salvation, praying to God that “her daughter Falconilla may live in eternity” (29). In this exchange of protection, even the dead Falconilla is afforded agency, appearing to her mother in dream and telling her to “receive this stranger, the forsaken Thecla, in my place, that she may pray for me and I may come to the place of the just.” (28). Thecla serves as a proxy for another woman, both as a comfort to a grieving mother and as a spiritual agent in her own right; manifestations of power flow multi-directionally and mutually here.

However, perhaps the most obvious example of Thecla’s positioning in a milieu of powerful females occurs when she is thrown to the wild beasts: her miraculous self-baptism is bookended by instances of female protection, and enriched at every step of the way by the reactions of women as witnesses. When lions and bears are set upon Thecla, a lioness fights them off, and we are told that “the multitude of the women cried aloud” (33). When the lioness dies in the process of killing a lion who “had been trained to fight men,” the women “cried the more since the lioness, her protector, was dead.” With her protection gone, Thecla takes the drastic step of self-baptism in a pit of vicious seals, despite the women’s weeping and admonishment “Do not throw yourself in the water!” Like Margaret, Thecla chooses to disregard the advice of a group of women who are unable to understand the profundity of her individual power, instead claiming salvation for herself. But unlike Margaret, Thecla simultaneously relies on the protection of these women; after “fiercer animals” (35) are released post-baptism, the women in the arena throw petals, nard, cassia, and amomum at the bests so they become “hypnotized.” Though Thecla’s baptism saves her soul, these women’s perfumes save her life. It is especially remarkable that their tools of choice are traditionally feminine and even frivolous cosmetics. After one more attempt to set beasts on Thecla, which fails due to the “burning flame around her,” the games end and Thecla is free to live out the rest of her days. Thus, although Thecla performs her climactic self-baptism through her unique spiritual skill, she survives only through the communal efforts of a cast of women: Queen Tryphaena, the lioness, and the witnesses. Yet the representation of women’s relationships in this text is neither monolithic nor wholly positive; it is important to remember that Thecla still performs her baptism in opposition to the wishes of other women, and after being condemned to death by her own mother.

Although the events of Margaret and Thecla’s stories mirror each other in important ways, I think it is equally important to note the ways in which they diverge, most notably in their positioning of the protagonist in relation to other women. In Margaret’s story, a self-baptism becomes a sign of singularity in opposition to the inherent weakness of women; in Thecla’s, it is facilitated by, commented on, and opposed by a host of other women who are powerful agents in their own right, for good or for evil.

Works Cited

“The Acts of Paul.” The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation. Ed. Elliott, J. K.: Oxford University Press, 1991. Oxford Scholarship Online. https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.proxy.uchicago.edu/view/10.1093/0198261829.001.0001/acprof-9780198261827-chapter-23.

Gregory, Megan. “Exposing a Transcorporeal Landscape in the Lives of St. Margaret of Antioch.” Magistra, vol. 21, no. 2, Wint 2015, pp. 92–111. proxy.uchicago.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLAn3838837&site=eds-live&scope=site

Grogan, Marie Schilling. “Baptisms by Blood, Fire, and Water A Typological Rereading of the Passio S. Margaretae” Traditio, vol. 72, Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 377–409, www.jstor.org/stable/26421465

Other Interesting Reading about Margaret:

Dresvina, Juliana. A Maid with a Dragon: The Cult of St Margaret of Antioch in Medieval England. First edition. Oxford University Press, 2016.

Beresford, Andrew M. “Torture, Identity, and the Corporeality of Female Sanctity: The Body As Locus of Meaning in the Legend of St Margaret Of Antioch”. Medievalia, Vol. 18, no. 2, 1, pp. 179-10, https://raco.cat/index.php/Medievalia/article/view/308813.