Water in Andreas

Andreas gives the ocean many names: the whale-road, the formidable waterways, the menace of the water, the salt sea-streams, the cold waters. The ocean roars, jostles, surges, and encroaches. The epithets of the ocean mirror the epithets of God. In fact, one of God’s names is “the Sentinel of the Sea.” Andreas does not treat the ocean as a mere means of transport or geographical feature. The ocean becomes a…

Ironic Heroism in Andreas

In her article on “Beowulf and Andreas,” Irina Dumitrescu highlights the irony of Andrew’s heroic depiction.[1] His valor as a courageous warrior and leader of men is praised throughout the poem to an extent that seems deliberately exaggerated, and sometimes even down right sarcastic, in light of his actions. For instance, we are introduced to Andrew as “the man of bold free-will,” whom God has decided to task with rescuing…

The Obscenity of Seeing Pain: From Susan Sontag to Christ Crowned with Thorns

The modern era has forgotten the genealogy of the view on suffering. It defines suffering as pejorative, something mistaken and ought to be avoided and condemned. The negativity of suffering is falsely taken to be universal. Rather, the negativity of suffering is a social narrative specific to our age. In Regarding the Pain of Others, in Susan Sontag’s discussion of Bataillie’s obsession with contemplating the photograph capturing a prisoner undergoing…

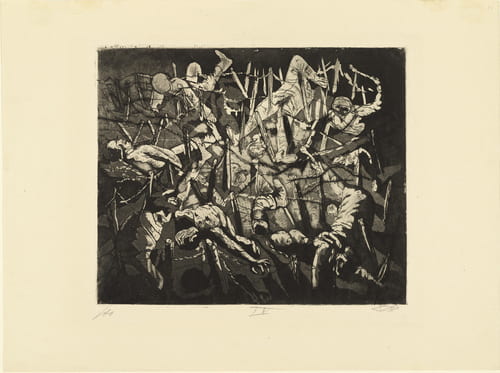

The Beauty in Horror

“On his way up from the Piraeus outside the north wall, he noticed the bodies of some criminals lying on the ground, with the executioner standing by them. He wanted to go and look at them, but at the same time he was disgusted and tried to turn away. He struggled for some time and covered his eyes, but at last the desire was too much for him. Opening his…

Witnessing and the Body

Resurrection Slender neck and sweat-dampened forehead, tasting tongue and the clash of teeth, lungs filled with smoke from the late-burning lamp. The scratch of pen on parchment, lines curving around bodies as they sink into the blood-soaked earth. Inside out we feel it pulsing in our neck, hear it in our cotton-stuffed ears, the things we can no longer remember. The sound of the shutter, the…

Photographs and Events

The War Photographer reading that was done for Thursday really put the previous Sontag reading into perspective for me. Especially when Sontag mentions the quote, “The photographs are a means of making ‘real’ (or ‘more real’) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore” (Sontag 7). I believe that the same applies to the Guardian reading we did for this week. So…

Rhetorical Adversity in the Consolation of Philosophy and Paradise Lost

Written in 523 and 1674 AD respectively, Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and John Milton’s Paradise Lost are crucial works of Christian prose and poetry. Despite their clear promotion of the Christian faith, the two works rely on the literary and religious elements of classical Greece and Rome to convey their message. In this post, I aim to highlight two similarities between these works regarding their treatment of classical influences and…

Interpreting Blood: Saint Margaret & Alypius

Group: Spencer, Jonah, Spencer, Jo Imagine brutal slasher horrors with flesh being ripped from bone and dripping chainsaws. The victims scream and plead for their lives. Blood sprays across the walls, the ceilings, and the camera. Viewers might flinch, or cover their eyes and look away. There is something so visceral and gruesome about blood. Imagine anything awful; imagine that scene from a horror movie where the victim is torn…

The Authorization of Suffering as a Tool of Conversion in Andreas

Andreas is a book of the travels and adventures of St. Andrew, or Andreas, as he attempts to save St. Matthew from a cannibalistic race of Mermedonians. However, it also allows for an inspection of the saintly suffering of a loyal follower of God, and how God’s reaction to Andreas’s torture reveals what God’s role is when faced with the suffering of his followers. At one point in the poem,…

The Maturing of Margaret’s Relationship with God

Maragaret’s travails as a saint are pointedly isolated from human supporters. She is put to trial against her attackers, with only Theotimius secretly nourishing her. Not only does she face Olibrius alone, but her family opposes the support she receives from God. Before Olibrius captures her, she is still religiously persecuted. As Theotimius explains, “she was very hateful to her father, but very dear to God” (115). The sentence structure…