Liz Carvalho

University of British Columbia

The gold mask of Tutankhamun might not be the first object that comes to mind when one thinks of the wonders of Egypt, but it’s arguably one of the most famous ones. Tutankhamun did not reign for a long period, but he established the return of the old gods after the Amarna period, characterized by the worship of only one deity. He changed his name to become closer to Amun, the creator god, restored Thebes as the religious center, and died young. In his tomb — relatively modest considering his abrupt demise at a young age due to health conditions, which led to a rushed burial with fewer pieces, instead of containing the amassed wealth of a long reign — there can be found almost 6,000 objects, the most memorable one being the gold mask. However, that is not the focus of this article, rather, the shabtis, small figurines that could easily be overlooked in the sea of offerings sealed in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

According to the Encyclopedia of African Religion, the shabtis (also known as ushabti, shawabti, and other spellings) were figurines meant to accompany the deceased to the afterlife. Because the next world was deemed a mere continuation of this one, the deceased would still have the same responsibilities; and, since they had duties to perform, they would not be able to enjoy the peace death brings. Therefore, shabtis would be in charge of doing things for them. The earliest shabtis were made of a type of wood called sbawab, which perhaps has given the figurines their name,1 but through the course of the centuries they were made of several materials, the most popular ones being wood and faience, a type of stone with an eerie shine which made it especially suitable for this magic servant. The form ushabti, which translates to “answerer,” was more popular during the Late Period, referring to how it responded to commands given by its owner.2

Fig. 1. Shabti 110. Wooden shawabti figure. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=110-p0298. A zoomed in version of the the text in the figurine can be accessed in http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1605496024&qno=1&dfnam=110-c326a-2.

Shabti magic was not to be taken lightly. As Silver states in What Makes Shabti Slave?, shabtis agreed to be slaves in return for an immortal existence in the afterlife, from being elevated from an inanimate object into a living one.3 The craftsman would use a magic ritual from Chapter VI in the Egyptian Book of the Dead to bring it to life, called the Shabti Spell, which would be inscribed into the figurine. The formula was to be spoken over a brick of unbaked clay. The formula would command and instruct the figurine to perform the work for the deceased in the afterlife, and the shabti would reply that they were there for that purpose as agreed.4 Shabtis made by authorized makers (such as people affiliated with temples) had superior value, because only then could the clients be sure that the shabtis would perform their duties in the beyond and not break the magic contract. Shabtis could be made by independent artisans, but they could not provide the same legal guarantees of performance that authorized makers would.5

Kathryn Howley offers in her article on shabtis a different perspective regarding how humans interact with small figurines and the way that applies to shabtis. She raises an intriguing point: today, Shabtis are the most numerous funerary item that have remained from antiquity, and, even then, only a small proportion of them have survived; thus, the sheer number that we possess can give an idea of how crucial they were to Egyptian funerary culture.6 A tomb could have from one to hundreds of shabtis, depending on the rank of the deceased. No wonder Tutankhamun had over 400 of them.7

Shabtis were in use for approximately 2,000 years, from about 2000 BCE until the end of the Ptolemaic period in 31 BCE.8 They could appear in all types of burials: of women and men, of elite and lower status individuals (not so low as the common person, but they were not reserved for royalty). They could be of various sizes, from a couple centimeters to half a meter (as seen in the examples in the tomb of Tutankhamun), but usually they would average about 15cm.9 Their small size encouraged them being handled and looked at up close for detailed examination. Also, they were miniature humans, and were treated as such, like with the linen and box “burials” seen in some of the shabtis in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Howley says that it’s likely that the boxes had more decorative than religious functions, and they complemented the atmosphere of the tomb instead of having magic properties.10The shabtis could be similar in appearance, but each was unique;11even if they were “mass produced,” their painting could still be different. A grouping of different sizes, materials, and styles of shabtis would contribute to this procession that was accompanying the deceased to work on their behalf.

In certain royal tombs there are specific rooms for the shabtis, such as in the tomb of Ramesses IV.12 Perhaps Tutankhamun’s tomb did not have those because of the hurry to give him a proper burial. As Reeves explains, 413 shabtis were buried with the king, 365 for each day of the year, 36 overseers for every week (weeks were 10 days long), and 12 monthly overseers. Of those 413, the full shabti spell was only found in 29, and the remaining ones had only the king’s name and title. The quality ranged from ordinary to spectacular. For them, a staggering 1,866 miniature agricultural implements were made to complement the shabits. In his tomb, the figurines were “distributed between the Treasury and the Annexe,”13 with 236 shabtis in the Annexe, 176 in the treasury and one from the ending chamber.14

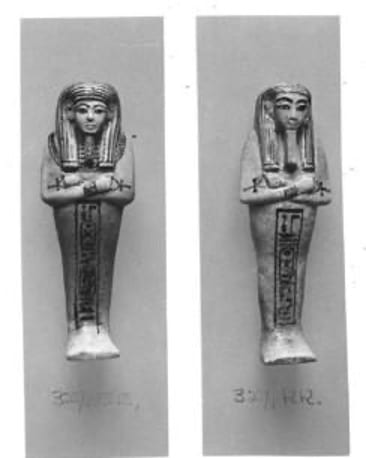

The Griffith Institute hosts the Howard Carter archives, which possess a thorough analysis of the complete collection, made by Howard Carter with photographs by Harry Burton. The shabtis comprise around ten percent of the assemblage of artifacts in the tomb. Many of them are almost identical to one another. Most were found in groupings inside wooden boxes, with some wrapped in linen. Because the majority are very similar, I will choose one of each type to talk about. Shabtis with three-digit reference numbers are sourced from the Griffith Institute Catalog, and those with five-digit reference numbers from the Global Egyptian Museum. For descriptions and high resolution images, the Global Egyptian Museum has three of the 431 shabtis on display.15

Fig 2. Shabti of Tutankhamun’s tomb JE 60830 from the Global Egyptian Museum Archive. Edited by Shereen Abd El Haleem. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/record.aspx?id=14815.

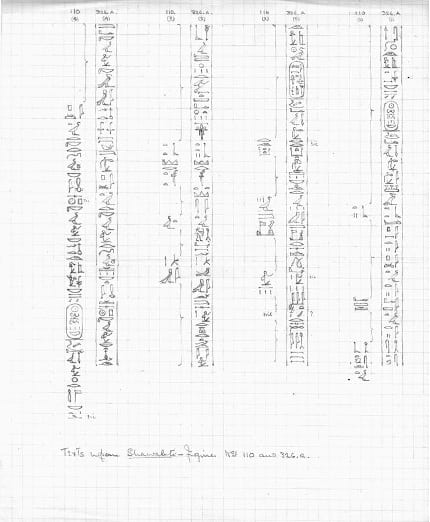

The writing under them can be the same among different shabtis, as can be seen in the comparison between figurines 110 and 326a made by Carter (see fig. 3),16 or divergent — even in the same kiosk17 the writing was not necessarily the same, as shown in 319a and attested by Reeves.18 They are similar enough to be together, but still have small differences between each other, as observed in the variant types of 319a-g and 319h-o. The quantity of text inscribed in the shabtis is remarkable. To read an inscription, one must approach it closely, perhaps even with a magnifying glass. The shabtis that have longer inscriptions, as not all of them contained the same text, would be inscribed on the body of the figure (like the 380 series, fig. 4), and the ones with less writing could then make do with smaller spaces, like the bottom of the feet (like the 318 series).

Fig. 3. Texts upon shawabti figures 110 and 326a. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation.

Fig. 4. 380a, crystalline limestone shawabti figure (first from left to right). Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=380a-p1686.

The biggest kiosk is the one numbered 327, containing forty faience shabti, made in white or blue faience, which don’t carry anything in their hands. Sometimes shabtis held ankhs, yokes, picks and hoes, implements usually made of copper, though they could also be in faience as described in the 329 entry. Other times they held the crook and flail (in the most recognizable mummy pose from the movies), and other times they held nothing.

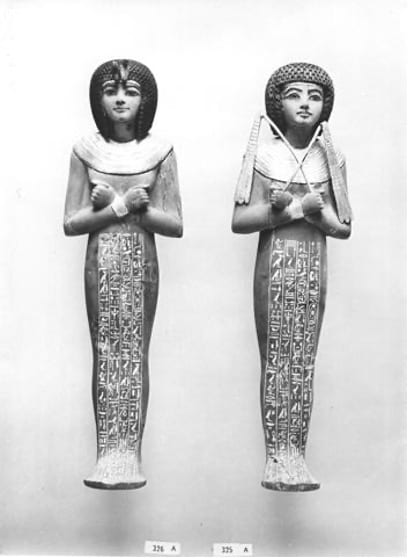

My assumption is that, as there were many functions to be performed by the deceased, these various implements indicate that the shabti holding them had specific objectives and intentions. In that case, the ankh would be a symbol of life (ironically, in the afterlife), which could indicate a peaceful beyond (327gg has ankhs in both hands, as seen in fig 4). The flagellum was associated with Osiris and would be used to ward off spirits. Perhaps 325a, which possesses two flagella (see fig. 6), as Carter enthusiastically described,19 is a specialist in that function. According to Stewart, starting with the time of the pharaoh Tuthmosis IV, shabtis were provided with agricultural tools. “The crook was an early tool used by shepherds while the flail was a means both of herding goats and of harvesting an aromatic shrub known as the labdanum,”20 and the tools were related to Osiris, who was originally an agricultural and fertility deity. The Osiris symbols were almost exclusively used by royal shabtis. Curiously, Osiris being related to death and the earth at the same time can also be seen in Greek mythology, with Hades, and other chthonic deities.

Fig. 5. 327gg, holding ankhs on both hands (on the left). Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=327gg-c327eenn.

Fig. 6. 325a holding flagella on both hands (on the right). On the left, 326a, wearing the usekh collar. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=325a-p1538.

A king’s shabtis wore the royal accoutrements, like the crowns, and the uraeus. Each crown has a different meaning and symbolizes distinct areas of Egypt. The red crown (Deshret) was associated with Lower Egypt, the white crown (Hedjet) with Upper Egypt, and the double red and white crown (Pschent) with the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.21 We can see Tutankhamun’s shabtis wearing all of them. For the Deshret, 330c (see fig. 7), in wood, holding the sceptre and the flagellum (all three of them are holding the same symbols). For the Hedjet, 330e (see fig. 8), also in wood. Last but not least, the only figurine wearing the double crown Pschent in all 413 examples, is 330f (see fig. 8), also in wood.22 It is interesting to consider why there’s only one with the double crown. Perhaps he wasn’t thought of as a unifier of Upper and Lower Egypt, maybe because of his short rule. However, there is no concrete information about that. Nevertheless, it is a distinct specimen.

Fig. 7. 330c (on the right), wearing the Deshret crown. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=330c-p1047a.

Fig. 8. 330e (on the left, wears the Hedjet crown), and 330f (on the right, wears the Pschent crown) Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=330f-p1050.

On the subject of royal accessories, the uraeus was one of the most important. It was the insignia that denoted rank, for rulers, and was worn on crowns and headdresses. It was composed of either a snake alone or a snake and a vulture. Mirroring the split symbolism of the crowns, the snake represented Lower Egypt and the goddess Wadjet, and the vulture represented Upper Egypt and the goddess Nekhbet.23 This can be seen in the shabtis wearing the crowns mentioned above. In total, as stated by Reeves, “Eight different types of headdress are represented with and without uraeus and/or cobra, the most frequently occurring type being that wearing the archaic or tripartite wig, of which some 286 specimens of were noted.”24 Another relevant accessory was the usekh collar, which can be seen in 326a (fig. 6). This collar had “amuletic and prestigious connotations, being commonly bestowed as royal gifts.”25

Using a figurine to talk about specific characteristics is a desirable approach, and in that case, shabti 328c can tell us about materials and headdresses (see fig. 9). It was made of calcite, which is hard, strong and durable. It could also be called alabaster, and that seems to have been related to the goddess Bast,26 which if true, could make it a good choice for a magic statue fit for a king. The eyes are black and the sacred text is painted in blue, much like the ceilings of temples. It holds an ankh and a flagellum, and on the head it wears a Khat headdress. It is one of the fifty-six that wear it, and the Khat was originally a “table of offerings in temples and tomb chapels, in use from the earliest eras on the Nile.”27

Fig. 9. 328c/328cd. Made of calcite, black eyes and blue painted text. Khat headdress, ankh and flagellum. Uraeus of wood. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=328c-c328cd.

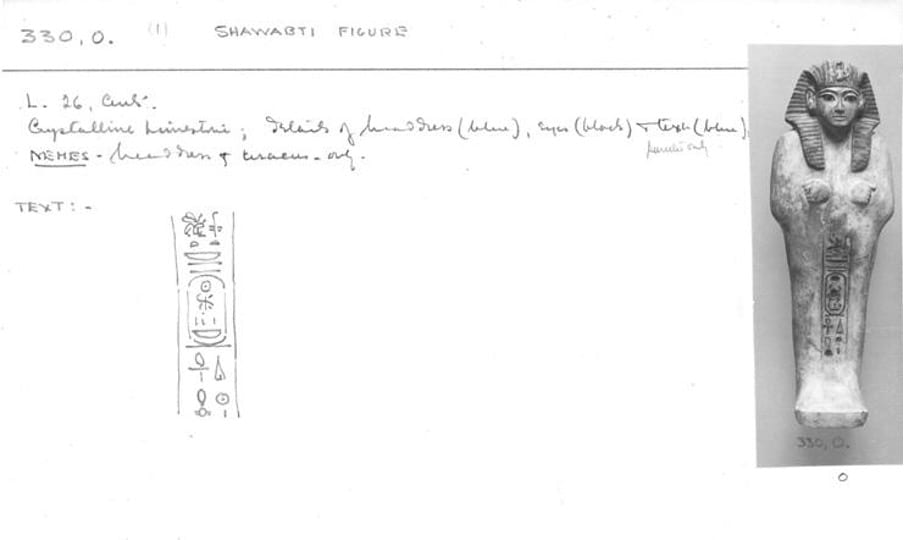

As mentioned above, calcite was one of the materials used for shabtis, but it was neither the only nor the most prevalent one. Figurine 329l was made of yellow limestone (see fig. 10) and 330o of crystalline limestone (see fig. 11). Limestone was abundant so it was a popular choice not only for shabtis but for buildings as well. Figurine 330o was also wearing a Nemes headdress, which is a type of striped royal headcloth, and can be found in 27 of the 431 shabtis.28

Fig. 10. 329l, made of yellow limestone with blue painted text. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=329l-c329l.

Fig. 11. 330o, made of crystalline limestone, with blue painted text, khat headdress and uraeus. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=330o-c330o.

Another material is exemplified by the 514 series: quartzite, a mineral found near Heliopolis,29 which was used frequently for statues and sarcophagi.30 There are ten of them, inside a wooden kiosk, decorated with an impression of Anubis over nine foes, found with its seal intact (as described by Carter). It is interesting to think about how this one was not disturbed, as most of them were. The opposite situation can be seen in the 330 series (the one that includes the crowned shabtis). It’s easy to tell that 330 has been disturbed because of the kiosk’s knobs being turned west and the upper layer not being like the other ones. The same is true of 512, which was found leaning precariously against a wall, carelessly thrown by dynastic plunderers (see fig. 12). It’s curious to think about how Tutankhamun’s tomb was found relatively undisturbed, and yet it did not survive untouched.31

Fig. 12. 512 is among the tossed wooden kiosks. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=512-p1227.

On secrets hidden and therefore protected from disturbances, Carter tells of Osiris figures (very similar to shabtis) 257, 258, 259 and 260, found in an extremely interesting position, that is, concealed inside niches in the walls (see fig. 13) in order to “repel the enemy of Osiris, in whatever form he may come.” Considering what Set did to his body,32 it sounds reasonable to protect the deceased from the same fate. The figurines were placed inside inset areas of the wall, and then the opening was covered in limestone and plaster and painted to match. Placed strategically on the four cardinal points, visually covering the entire area, they seem like guardians, looking over the king as he rested, one last line of defense. Shabtis would protect the king in the afterlife, but these figures would keep his body (and therefore the offerings) safe.

Fig. 13. 257, Osiris figure. Photograph by Harry Burton. From the Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1611907268&qno=1&dfnam=259-p0884b.

Even though Tutankhamun’s tomb was most likely put together in a hurry, there was an army of shabtis fit to make the king’s afterlife the best one he could possibly have. Some were alike, others were different, but regardless of size or material they all served the same purpose. Considering how much from antiquity has not survived to our day, this tomb was a magnificent find. So much can be learned from the shabtis alone, and immeasurable knowledge can be acquired from the other 5000 objects buried with the king. They form a microcosm of that civilization, from which we can deduce the depth and complexity of its thought and practices from what they left behind. The tombs are like mirrors of what society was and tell an engaging and striking story. Although the shabtis were small, their role was vital, and it is no wonder that they were in use for centuries. After all, there is nothing more human than trying to enjoy the time we have left, and even after death that was still a big concern.

Bibliography

Asante, M. K., & Mazama, A. Encyclopedia of African Religion, vol 1, pp. 614-614, s. v. “Shawabti.” SAGE Publications, Inc, 2009, [https://www.doi.org/10.4135/9781412964623.n383], (accessed September 19, 2021).

“Book of the Dead Chapter 6.” University College London , 2002. [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/literature/religious/bd6.html], (accessed September 19, 2021).

Bunson, Margaret R. Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York: Infobase Learning, 2020.

Dorman, Peter F. “Tutankhamun.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed September 19, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tutankhamun.

“Flagellum.” The Global Egyptian Museum | Flagellum. Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/glossary.aspx?id=154.

Harper, Douglas R. “Alabaster (n.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed September 19, 2021. https://www.etymonline.com/word/alabaster.

Howley, Kathryn E. “The Materiality of Shabtis: Figurines over Four Millennia.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, no. 1 (2020): 123–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959774319000313.

Knowles, Elizabeth. “Pschent.” The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Oxford University Press, 2005. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198609810.001.0001/acref-9780198609810-e-5745.

Mark, Joshua J. “Ancient Egyptian Symbols.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Accessed September 19, 2021. https://www.ancient.eu/article/1011/ancient-egyptian-symbols/.

“Quartzite.” The Global Egyptian Museum | Quartzite. Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/glossary.aspx?id=309.

Reeves, Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames and Hudson, 1990.

Silver, Morris. “What Makes Shabti Slave?” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52, no. 4 (2009): 619–34. https://doi.org/10.1163/002249909×12574071439813.

Stewart, H. M. Egyptian Shabtis. Shire Egyptology 23. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications, 1995.

“The Global Egyptian Museum: JE 60833.” Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/record.aspx?id=14811.

“The Global Egyptian Museum: JE 60824 A.” Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/record.aspx?id=14765.

“The Global Egyptian Museum: JE 60830.” Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/record.aspx?id=14815.

Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation | The Griffith Institute. Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/discoveringTut.

Wallis, Budge E A. The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Ani. https://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ebod/, 1895.

- M. K. Asante& A. Mazama, s.v. “Shawabti,” in Encyclopedia of African Religion (Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2009), 614. ↩

- H. M. Stewart, Egyptian Shabtis, Shire Egyptology 23 (Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications, 1995), 13. ↩

- Silver, Morris. “What Makes Shabti Slave?” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52, no. 4 (2009), 620. ↩

- “The shabti figure replies: “I will do (it); verily I am here (when) thou callest,” Egyptian Book of the Dead, 362. ↩

- Silver, 628. ↩

- Howley also states that “the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has 473 examples listed on its online catalogue; the Louvre more than 7000“ (“The Materiality of Shabtis: Figurines over Four Millennia.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 30, no. 1: 125). ↩

- “Tutankhamun, for example, owned 413, supplied with 1866 miniature agricultural implements” (Reeves, Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames and Hudson, 1990, quoted in Howley, 125). ↩

- Howley, 125. ↩

- Howley, 127. ↩

- Howley, 136. ↩

- Howley, 135. ↩

- Stewart, 11. ↩

- Stewart, 11. ↩

- Nicholas Reeves, The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990), 136. ↩

- They have a surprising amount of detail: not only are the images themselves very high quality, but the descriptions as well (see fig. 2 below). However, 60833 has been miscategorized and has the same image as 60824A, an unfortunate mistake. ↩

- Howard Carter, “Carter #110,” The Griffith Institute, accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1605496024&qno=1&dfnam=110-c326a-2. ↩

- Kiosks guarded shabtis and can be seen in Fig. 12. ↩

- Howard Carter, “Carter #319a,” The Griffith Institute, accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1605496024&qno=1&dfnam=319a-c319ag ↩

- Howard Carter, “Carter #325a-1,” The Griffith Institute, accessed September 19, 2021, http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/perl/gi-ca-qmakedeta.pl?sid=50.92.73.71-1605496024&qno=1&dfnam=325a-c325a-1. Shabti number 325 is described as having “Ebony wig; usekh-collar (heavily gilt) and mankhet; two flagella!!! in hands; bracelets (heavily gilt).” ↩

- Stewart, 37. ↩

- Elizabeth Knowles, s.v. “Pschent.” The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (Oxford: Oxford University Press,2005). ↩

- Reeves, 138. ↩

- Margaret R. Bunson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , s. v. “Uraeus”, pp 455. New York: Infobase Learning, 2020. ↩

- Reeves, 138. ↩

- Stewart, 39. ↩

- Douglas R. Harper, s.v. “Alabaster (n.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. Accessed September 19, 2021. https://www.etymonline.com/word/alabaster. ↩

- Bunson, 32. ↩

- Reeves, 138. ↩

- Bunson, 288. ↩

- “Quartzite.” The Global Egyptian Museum (Accessed September 19, 2021. http://www.globalegyptianmuseum.org/glossary.aspx?id=309). ↩

- Dawkins contributed a couple years ago an article to Forbes on this subject: David Dawkins, “’Stolen’ Tutankhamun Bust Puts Britain’s Museums and Auctioneers Back under the Spotlight,” Forbes (Forbes Magazine, July 5, 2019). ↩

- According to myth, Set kills his brother Osiris, ruler of Egypt, and dismembers his corpse, scattering the pieces throughout land. Osiris’s wife, Isis, searches for the body parts and manages to bring the god back. However, he is now god of the dead, no longer having a place ruling over the living, and that role is taken over by his son Horus. ↩