Areas of Research

The External Environment

(The social and physical environment)

Our ongoing work examining the external environment makes use of human rating and behavioral data in combination with computational methods, including machine learning and edge sensing, to study our social and physical surroundings. Read descriptions of some of these projects below.

Using Computer Vision to Study Visual Features of Chicago Neighborhoods

Within the field of criminology, scholars have argued that people have greater ability to take action against crime (calling 911, verbally admonishing a perpetrator, etc.) when they can see easily through the environment. For example, homeowners are more easily able to detect would-be burglars if the sight-lines from their windows are not obscured by trees. Similarly, it has been argued that people are more motivated to actively respond to crime when they live in an area they perceive to be aesthetically pleasing. Although social scientists have many ideas about how visual features of places impact behavior, visual features have historically been challenging to measure, making it hard to test such ideas. To measure visual features, we are having participants rate Google Street View images, taken from across Chicago, on features like environmental transparancy and aesthetic preference. With these human ratings, we will have a “training dataset” from which a computer vision AI model can learn to assign transparancy or preference scores to 200,000 images representing every block in Chicago. By averaging scores of images within the same neighborhood, we plan to create citywide neighborhood maps of visual features which, in conjunction with data provided by the Chicago Police Department, will allow us to evaluate whether places with certain types of visual features tend to experience more crime.

To read more about this project, click here

To read about crime prevention through environmental design, click here

Perceptions of Life Expectancy Influence Delay Discounting

Delay discounting describes the decrease in subjective value of an outcome as time until the outcome’s occurrence increases. For example, a person exhibiting high rates of delay discounting would be willing to forgo a larger reward made available at a later time ($20 accessible in 4 weeks) in favor of a smaller reward available immediately ($5 accessible right now), whereas a person exhibiting low rates of delay discounting would prefer the larger, but later, reward. Our project examines the effect of a number of biosocial (e.g., age at which one had their first child) and economic (e.g., median household income) variables on delay discounting in order to better understand how one’s social and economic environment influences their approach to decision-making. Preliminary results suggest that rates of delay discouting differed based on whether one expects their friends to live longer or shorter lives, among other factors.

Perceiving Natural Resources May Consume Fewer Cognitive Resources

Interaction with the natural environment is known to have beneficial effects not seen during interaction with the urban environment. For example, our prior work finds that spending time in nature can increase positive affect and improve working memory. Attention Restoration Theory posits that the natural environment captures directed attention less, allowing for the restoration of cognitive resources. Our current work on this topic aims to understand why natural scenes might capture directed attention less than urban scenes. Using measures of memorability, edge magnitude, and spectral content, our findings suggest that, as compared to urban scenes, natural scenes contain less easily noticeable information. This difference in amount of easily noticeable information may explain why passive viewing of natural scenes consumes fewer cognitive resources than viewing of urban scenes.

Social Interaction Quality Across Neighborhoods

Much of our current research aims to understand how qualities of physical spaces affect interactions between individuals in different neighborhoods. However, the factors that contribute to perception of a social interaction as positive or negative remain largely undefined. How do people make judgements about social interaction quality? To examine this question, we will ask participants to view video clips of social interactions while moving a sliding scale to reflect how well the believe the interaction to be going. By analyzing these rating data with a factor-based AI approach, we can better understand what features human labelers may prioritize when assessing social interactions. We hope to apply this understanding at the neighborhood level by analyzing social interactions recorded by edge sensors around Chicago.

Understanding the Influence of Heat on Cognitive Performance

There is evidence that heat increases aggressive motivation and behavior, though it is difficult to discern whether increased violence seen during periods of high temperature is due to heat rather than changes in routine activity. For example, more violent crime is committed during the summer months. Is this increase in violence due to the heat itself or to the fact that more people are out and about during nice weather? Does heat affect behavior simply because it induces negative mood, or does the effect of heat extend beyond the induction of negative emotion states? Our study attempts to better understand how heat influences cognitive performance, with specific focus on aggression and impulsivity. During the study, participants will be seated in a sauna set and exposed to either heat stress (110 degrees F) or a neutral temperature while wearing a bioharness to measure physiological information, including core body temperature, skin temperature, and heart rate variability. In the sauna, participants will complete tasks assessing working memory and cognitive flexibility as well as a novel task assessing reactive aggression (RC-RAGE task).

To read about heat and violence, click here

To read about heat and cognitive performance, click here

To read about the RC-RAGE task, designed by lab alum, Kim Meidenbauer, click here

Prospect-Refuge Theory and Aesthetic Preference in Urban Spaces

Architects, urban planners, and researchers alike attempt to engineer the optimal urban environment, one that pedestrians aesthetically prefer. Prospect-Refuge Theory posits that we have an evolutionary preference for environments that offer a sense of refuge (a place to hide, ensuring safety) while also having prospect (the ability to survey the area around you for resources, potential threats, other organisms). In the present study, we aim to further examine the validity of prospect-refuge theory in the urban environment. In the first iteration of this project, we used online survey tools to collect human ratings of prospect and refuge of 552 images taken from Google Street View. At present, we are working to collect prospect and refuge ratings of a larger image set that is more representative of Chicago neighborhoods.

To read about Prospect-Refuge Theory, click here

To read about some of our previous work on the internal environment, see below.

Environmental preferences in children

Adults demonstrate pervasive preferences for natural environments over urban ones, and while research demonstrates that people of all ages benefit from nature exposure, environmental preferences have only been assessed in adult populations. To test whether a preference for natural environments was also present in children, a large, diverse sample of 4-to-11-year-old children and their parents completed a tablet-based environmental preference rating task. Unexpectedly, kids showed a preference for urban environments and this preference weakened with age. Children’s preferences were overall, more similar to those of their own parent/guardian relative to other adults in the study, and the similarity between child and parent preferences increased with age. Interestingly, nature exposure (near home, school, or at play) did not predict children’s environmental preferences, but children with more nature near their homes did have lower levels of inattentiveness, controlling for household income. Together, this suggested that 1) the preference for natural environments develops or is learned over time, and 2) that exposure to nature is still related to improved cognitive functioning in children who do not show a preference for natural environments.

Click here for our article

Environmental Influences on Thought Content

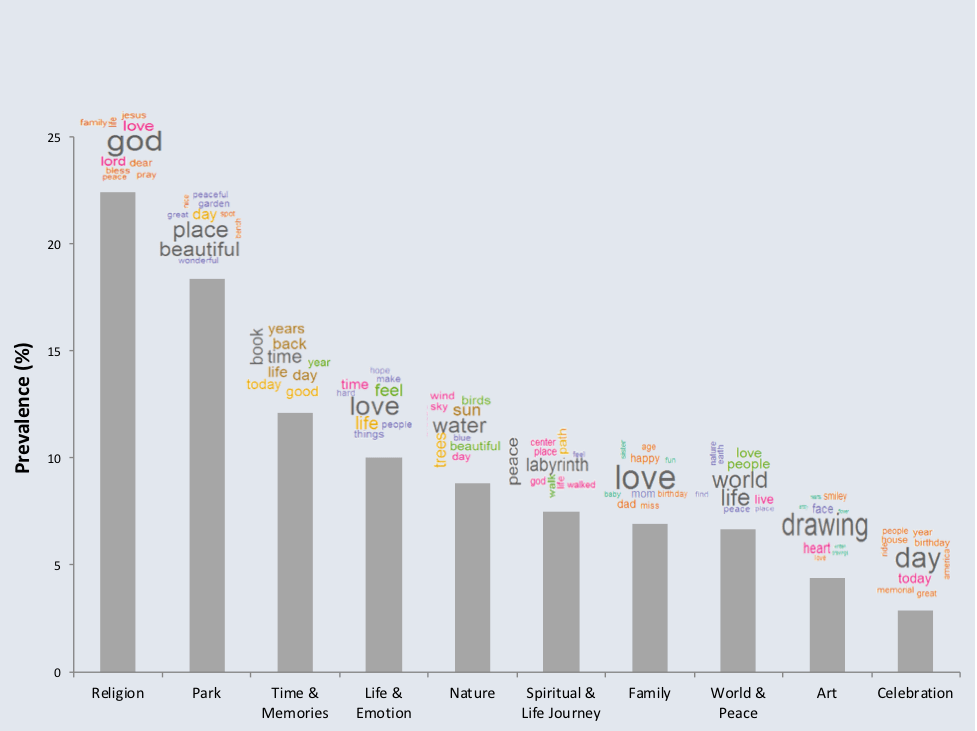

In this line of work, we investigate the influence of the physical environment on thought content. In one set of studies, we used topic modeling to determine topics that were commonly thought about by visitors to parks (Figure 1). We then saw how the prevalence of these topics varied by park and if that variation was associated with the visual features that were present in the parks. First, and unsurprisingly, we found that people were more likely to think about “Nature” in parks that looked more natural. More surprisingly, we also found that people were more likely to think about a topic related to “Spiritual & Life Journey’ in parks with more non-straight (curved or jagged) edges. We experimentally tested these findings by showing people pictures with different levels of naturalness or non-straight edges and found that these patterns of thoughts replicated, demonstrating a potential causal effect for visual features influencing thought content. We then created scrambled edge versions of the same images which retained their edge features but removed the overt semantic content (Figure 2). We extend previous findings by showing that non-straight edges retain their influence on the selection of a “Spiritual & Life Journey” topic after scene identification removal. These results strengthen the implication of a causal role for the perception of low-level visual features on the influence of higher-order cognitive function, by demonstrating that in the absence of overt semantic content, low-level features, such as edges, influence cognitive processes.

Evidence and Theory for Lower Rates of Depression in Larger U.S. Urban Areas

Depression is the global leading cause of disability and related economic losses. Cities are associated with increased risk for depression, but how do depression risks change between cities? We developed a mathematical theory for how the built urban environment influences depression risk and predict lower depression rates in larger cities. We demonstrate that this model fits empirical data across four large-scale datasets in U.S. cities. If our model captures some of the underlying causal mechanisms, then these results suggest that depression within cities can be understood, in part, as a collective ecological phenomenon mediated by human social networks and their relationship to the urban built environment.

The role of preference in the emotional benefits of nature exposure

Nature interactions have been demonstrated to produce reliable affective benefits. While adults demonstrate strong preferences for natural environments over urban ones, it is not clear whether these emotional benefits result from exposure to nature stimuli per se, or whether analogous benefits would be observed from viewing anything that is highly preferred. This question was examined using a set of pre-registered experiments. In one study using preference-equated stimuli, we find that changes in positive and negative affect are not greater for nature images when they are just as preferred as urban images. Next, we induced a negative mood in some participants to see if nature’s affective benefits would be more evident when baseline emotional state was low and compared affect change after viewing really beautiful nature images with equally beautiful cityscapes and cute animals. Results showed that baseline mood didn’t matter, and there was no added benefit of viewing nature images over cityscapes or animals, but individuals’ own ratings of how much they liked the images did predict change in affect. Lastly, we found that preference ratings (“liking”) were equivalent to aesthetics ratings (“beauty”), suggesting that there isn’t some additional factor beyond beauty that makes nature images so highly preferred. Though this study was limited to using nature images and not actual nature exposure, the results suggest that nature has a positive effect on our mood because it is such a highly preferred environment.

Click here for our article

Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center

Studies have shown that natural environments can enhance health and here we build upon that work by examining the associations between comprehensive greenspace metrics and health. We focused on a large urban population center (Toronto, Canada) and related the two domains by combining high-resolution satellite imagery and individual tree data from Toronto with questionnaire-based self-reports of general health perception, cardio-metabolic conditions and mental illnesses from the Ontario Health Study. Results from multiple regressions and multivariate canonical correlation analyses suggest that people who live in neighborhoods with a higher density of trees on their streets report significantly higher health perception and significantly less cardio-metabolic conditions (controlling for socio-economic and demographic factors). We find that having 10 more trees in a city block, on average, improves health perception in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $10,000 and moving to a neighborhood with $10,000 higher median income or being 7 years younger. We also find that having 11 more trees in a city block, on average, decreases cardio-metabolic conditions in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $20,000 and moving to a neighborhood with $20,000 higher median income or being 1.4 years younger.

Click here for our article

Is the preference of natural versus man-made scenes driven by bottom-up processing of the visual features of nature?

Previous research has shown that viewing images of nature scenes can have a beneficial effect on memory, attention, and mood. In this study, we aimed to determine whether the preference of natural versus man-made scenes is driven by bottom–up processing of the low-level visual features of nature. We used participants’ ratings of perceived naturalness as well as esthetic preference for 307 images with varied natural and urban content. We then quantified 10 low-level image features for each image (a combination of spatial and color properties). These features were used to predict esthetic preference in the images, as well as to decompose perceived naturalness to its predictable (modeled by the low-level visual features) and non-modeled aspects. Interactions of these separate aspects of naturalness with the time it took to make a preference judgment showed that naturalness based on low-level features related more to preference when the judgment was faster (bottom–up). On the other hand, perceived naturalness that was not modeled by low-level features was related more to preference when the judgment was slower. A quadratic discriminant classification analysis showed how relevant each aspect of naturalness (modeled and non-modeled) was to predicting preference ratings, as well as the image features on their own. Finally, we compared the effect of color-related and structure-related modeled naturalness, and the remaining unmodeled naturalness in predicting esthetic preference. In summary, bottom–up (color and spatial) properties of natural images captured by our features and the non-modeled naturalness are important to esthetic judgments of natural and man-made scenes, with each predicting unique variance.

The perception of naturalness correlates with low-level visual features of environmental scenes

Previous research has shown that interacting with natural environments vs. more urban or built environments can have salubrious psychological effects, such as improvements in attention and memory. Even viewing pictures of nature vs. pictures of built environments can produce similar effects. A major question is: What is it about natural environments that produces these benefits? Problematically, there are many differing qualities between natural and urban environments, making it difficult to narrow down the dimensions of nature that may lead to these benefits. In this study, we set out to uncover visual features that related to individuals’ perceptions of naturalness in images. We quantified naturalness in two ways: first, implicitly using a multidimensional scaling analysis and second, explicitly with direct naturalness ratings. Features that seemed most related to perceptions of naturalness were related to the density of contrast changes in the scene, the density of straight lines in the scene, the average color saturation in the scene and the average hue diversity in the scene. We then trained a machine-learning algorithm to predict whether a scene was perceived as being natural or not based on these low-level visual features and we could do so with 81% accuracy. As such we were able to reliably predict subjective perceptions of naturalness with objective low-level visual features. Our results can be used in future studies to determine if these features, which are related to naturalness, may also lead to the benefits attained from interacting with nature.

Click here for our article

Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain

How similar are the experiences of social rejection and physical pain? Extant research suggests that a network of brain regions that support the affective but not the sensory components of physical pain underlie both experiences. Here we demonstrate that when rejection is powerfully elicited—by having people who recently experienced an unwanted break-up view a photograph of their ex-partner as they think about being rejected—areas that support the sensory components of physical pain (secondary somatosensory cortex; dorsal posterior insula) become active. We demonstrate the overlap between social rejection and physical pain in these areas by comparing both conditions in the same individuals using functional MRI. We further demonstrate the specificity of the secondary somatosensory cortex and dorsal posterior insula activity to physical pain by comparing activated locations in our study with a database of over 500 published studies. Activation in these regions was highly diagnostic of physical pain, with positive predictive values up to 88%. These results give new meaning to the idea that rejection “hurts.” They demonstrate that rejection and physical pain are similar not only in that they are both distressing—they share a common somatosensory representation as well.