Apr 27, 2020 | Immunology, Research, Transplantation

by Peter Wang

When I started college at UChicago, I thought “This is going to be the best four years of my life! Don’t waste any of it!” I would try out for water polo, make lifelong friends, and jump into research. I wanted to become a doctor in the future and was eager to get my hands dirty.

The spring of my first year, I joined the lab of Maria-Luisa Alegre, MD, PhD. Her lab studies the responses of T-cells, the guardians of the body against foreign invaders, in solid organ transplantation: T-cell tolerance to donor grafts, the impact of infection and inflammation on anti-graft immunity, and interactions between the host immune system against the transplant and microbiota at different body sites.

Roughly 40,000 transplants were performed last year, and over 100,000 people are still on the national transplant waiting list. What the Alegre lab uncovers about the immune mechanisms involved in transplant rejection and tolerance has important implications for the health of these transplant recipients.

My first year as a scientist went by quickly, like when you’re driving somewhere and you lose your sense of time. I found my own groove, balancing chemistry classes in the morning with mouse experiments in the afternoon, not to mention lots and lots of pipetting. I felt I was doing something important, and life couldn’t be better.

Then my life—everybody’s lives—hit a massive speed bump. In March 2020, we were faced with the looming COVID-19 pandemic. My daily routine quickly shifted to life under lockdown: online classes, no labs, stress and anxiety and facing the anti-climactic reality that all I could do to help was to stay indoors. I had so much to look forward to that month; not only exciting experiments, but also a water polo tournament in Des Moines—vanished.

This pandemic has undoubtedly affected the lives of millions of students, small business owners, and brave healthcare workers on the front lines. But I get to give you my perspective, that of the cohort I am joining—scientists—the people best positioned to get us out of this mess.

Scientists in immunology are all motivated by the desire to understand health and disease and improve human health. The more we know about the immune system, the better outcomes we can provide for patients experiencing cancer, organ failure, infection, and allergy.

To advance knowledge, many immunologists utilize unique mouse models. In studying transplantation, Dr. Alegre suggests that “mice are relatively easy to alter genetically, offering the smallest animal model in which it is still possible to transplant an organ (if you are a skilled microsurgeon) and which allows mechanistic investigations into how a given immune gene can lead to graft rejection or graft tolerance. These genes can then become therapeutic targets and improve patient outcomes.”

In the Alegre lab, we use mouse models to study T-cell responses following skin and heart transplantation. Many of our mice are transgenic; like genetically altered fruits or vegetables, our mice have T-cells or tissues engineered to express or lack certain genes and proteins. We use these as donors or recipients of transplanted organs or as sources of transplant-reactive T cells to understand the immune response to the graft.

Because of the limitations in the number of complex surgeries that can be performed in a day, we often plan and perform multiple mouse experiments simultaneously. In her lab, Alegre says that “many of our experiments look at the maintenance phase of transplantation tolerance, 30-60 days after transplantation. Our microsurgeon usually generates a continuous stream of transplanted mice of the various gene backgrounds to have a lineup of experimental mice that have already reached the desired time point.”

Confronted with the necessity to evacuate the lab, we knew there would be few, if any, people left to care for the mice. Soon, universities and labs across the world would ask researchers to wrap up all ongoing experiments and think long and hard about the mice they needed, freeze the embryos of rare and special strains, prioritize the young pups of unique strains, and in many cases, cull the rest.

“The week in which we had to shut down the lab and dramatically reduce our mouse colony was distressing,” Alegre said. “In the span of a week, we erased years of work, prioritized irreplaceable strains and sacrificed all non-essential animals. Mentoring experimental design, methods and data interpretation is obviously much less effective when bench experiments cannot be performed, impacting undergraduate and graduate education.”

Our final in-person lab meeting was heartbreaking. We prioritized our mice: the young and pregnant were spared, with the hopes of ramping up breeding once the lab shutdown is over. Alegre estimates that this crisis has caused a “setback of about a year to be where we were before the lab shutdown. Publication of our findings will be delayed until we can ramp up transplantation and get to the point where we can repeat experiments and generate new data.”

As we adjust to this newfound reality, many at UChicago and the Duchossois Family Institute are confident that our life-saving work will continue, but at a different time and pace. When asked about the future, Alegre expressed that “we scientists are resilient by nature, however we’ll miss the thrill of new discovery and the quiet satisfaction of doing something useful that advances scientific knowledge.” We’ve shifted to lab meetings and journal clubs via Zoom, and I am writing about our work now in a different way—for the public rather than in scientific journals for other researchers. But the sacrifice and isolation in the age of social distancing is one of our important duties as citizens, and saving lives is what I value most.

Peter Wang is a second-year undergraduate student in The College.

Apr 13, 2020 | Immunology, Microbiome

by Helen Robertson

In 1933, identical twin baby boys Oskar Stohr and Jack Yufe were separated as a consequence of their parents’ divorce. Their subsequent upbringings could not have been more different: Oskar was brought up as a Catholic in Germany and became an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth. Jack remained in the Caribbean where they were born, was Jewish, and even lived for a time in Israel. Yet when they were reunited some fifty years after they last saw each other they had an uncanny number of similarities. They shared thought patterns, walking gait, a taste for spicy food, and perhaps most unusually, a habit of flushing the toilet before using it.

The unfortunate separation of identical twins provides scientists with an exceptional laboratory for exploring the “nature vs nurture” conundrum. How much of our identity is conferred by our genes, and how much is a product of the environment in which we are raised? This is also true for our microbiome: twin studies have shown that the microbiomes of identical siblings are far more similar than those of fraternal twins, indicating that genes are at play.

UChicago researchers Alexander Chervonsky, PhD, and Tatyana Golovkina, PhD, are particularly interested in exploring how genetics—especially the genes that control our immune system— influence the composition of our microbiome. They chose to explore this question with mice.

Both mice and humans have two types of immunity: innate, “inborn” immunity, the first line of defense against pathogens, and adaptive immunity, in which immune cells are trained by the specific pathogens they encounter to fight off the same bad guys in the future.

To make sure all the mice used in the study started with the same microbes, Chervonsky and Golovkina needed to isolate them from the regular, bacteria-filled world. A normal mouse—much like a normal human—is born into an environment with trillions of bacteria, spread to them from their mothers and cagemates, their handlers, bedding, and food. Fortunately, UChicago’s special germ-free “gnotobiotic” mouse facility allows scientists to experiment on mice born and raised in an environment that hosts precisely zero bacteria, which make the mice experimental blank slates.

The researchers transferred microbes from a source mouse, raised in a conventional environment, to several strains of germ-free mice: some genetically identical, others with slight differences in their immune-response genes. In collaboration with computational immunologist Aly A Khan, PhD, they compared the resulting microbiomes to see if changes to immune system genes resulted in different types of microbial communities.

They found that differences in the adaptive—targeted—immunity caused minimal differences in microbial composition, and that those differences affected only certain strains of bacteria. Other types of bacteria even took advantage of the genetic differences and multiplied.

The team was surprised to discover that it was the innate immune response—the one the mice were born with, that needs no training: it was more active in shaping the microbiome. But even then, the total influence over the microbes in the mice’s gut was fairly small, meaning there were likely other genetic and non-genetic factors at play in determining how bacteria colonized and proliferated in the animals guts.

The team intends to look deeper into understanding how genes and microbes influence each other in developing animals. But this study sets a valuable benchmark for future microbiome work: closely documenting how the immune system worked here in germ-free mice means comparisons against other studies are standardized. Now we have a better idea of the “nature” side of the equation.

The Gnotobiotic Research Animal Facility is a vital asset for researchers at UChicago, and just one example of the gold standard approaches being used by the Duchossois Family Institute to improve our understanding of the underlying components of health and wellness.

Helen Robertson is a postdoctoral scholar in Molecular Evolutionary Biology at the University of Chicago, with a keen interest in science communication and science in society.

Apr 2, 2020 | Immunology, Microbiome, News Roundup

Chicago doctor whose blunt speech resonated with millions has another message

In a video PSA, UChicago Associate Professor Emily Landon asks people to stay home and help flatten the curve. (NBC 5 Chicago)

Argonne National Laboratory uses supercomputers to take on coronavirus

Stephen Streiffer, deputy laboratory director for science at Argonne, discusses the use of supercomputers to combat the coronavirus. (CBS Chicago)

Here’s where bacteria live on your tongue cells

UChicago’s Marine Biological Lab scientist Jessica Mark Welch maps how bacteria are grouped together on human tongue cells. (Science News)

A new, shelf-stable film could replace needles and improve global vaccination rates

This film requires no refrigeration and can be given by mouth. (Yahoo News)

How male and female immune responses differ

Sex-specific traits of the immune system, especially in the fat cells of the body, may explain the differences between the genders in their susceptibility to certain diseases. (Futurity)

Feb 28, 2020 | Food Allergies, Immunology

A selection of health news from the University of Chicago and around the globe curated just for you.

UChicago celiac disease researchers build a better mouse

Research breakthroughs on celiac disease depend in large part on a reliably valid animal model. Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, and researchers at the Duchossois Family Institute have rigorously demonstrated the mouse model they developed is a vital tool in making progress. (Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News)

Too many hospitalized kids get antibiotics they don’t need

Overuse poses an increasing threat to children, encouraging drug-resistant infections that are difficult or impossible to treat. Unfortunately, 25 percent of hospitalized children get inappropriate treatment. (Futurity)

Diagnosing deadly infections faster with new genomic tests

The time it takes to culture deadly bacteria and identify the right antibiotic can sometimes make the difference between life and death. Faster, more accurate identification of pathogens can save lives and reduce drug-resistant infections. (New York Times)

Benefits of getting a lung infection as a young adult?

After a young adult recovers from a lung infection, some immune cells that came to the rescue seem to stay in the lungs, protecting the patient against pneumonia in the future. (Futurity)

Janelle Monae and eating fish? UChicago doctor/chef breaks it down.

The singer/actress chalked up a scare about possible mercury poisoning to a pescatarian diet. Gastroenterologist Ed McDonald weighed in to relieve worry, with advice about the health benefits of eating fish. (Billboard)

Feb 21, 2020 | Immunology

by Elise Wachspress

Through the many posts on the WellNews blog, we’ve pointed out correlations between diet and disease, microbial diversity and wellness, sleep and neurological health. Science often progresses via experiments in which one variable is tested against one outcome, a binary approach that allows us to make definitive statements about causations—or at least correlations—between pairs of conditions.

But life—and our body systems—are messy. There are countless variables involved in keeping the human machine functioning. For starters: over 20,000 genes determine our body plan, direct the assembly of the proteins that power our cells, and lay out the immunological system that protects us from foreign intruders. Then there are the trillions of molecules in the air, water, soil, and food that we take in every day which can activate or deactivate those genes. There are the variables of temperature and sunlight, affecting our sleep cycles and how we manufacture our vitamins.

And there is the impact of the bacteria—more numerous than all our cells—with whom we share our bodies.

In this amazingly complex ecosystem, everything affects and is affected by everything else.

Recently, the world has been gob-smacked by another player in the human ecosystem: viruses. The virus COVID-19 is exerting an outsize influence on international travel, the supply chain, the economy, and the governments of China and Singapore, as well as the news media. The virus, really just a packet of molecules—not even really alive—is hard to detect until it has successfully infected cells. Now the global race is on to understand the “strategy” COVID-19 uses to get into our cells and replicate, often causing significant distress and sometimes death.

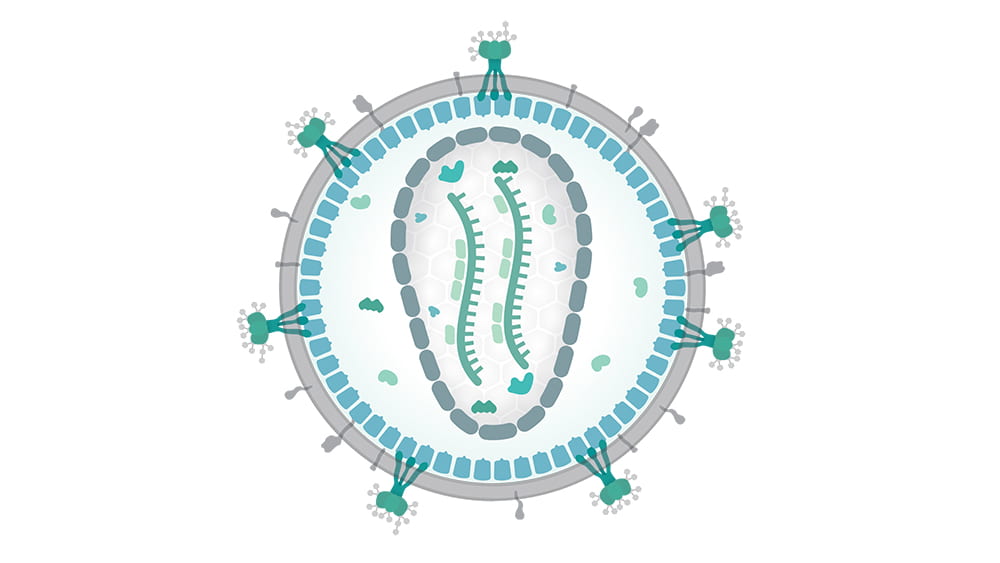

Not so long ago, another type of virus—the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV—initiated similar havoc. HIV is a retrovirus, a packet of RNA that inserts itself directly into cell genomes, and once inserted into cell DNA, continues replicating through generations of cells.

Tatyana Golovkina, PhD

Tatyana Golovkina, PhD, is an expert in retroviruses, how the immune system detects and attempts to neutralize them, and how the retroviruses fight back. In important research nearly a decade ago, Golovkina and her team demonstrated that retroviruses use certain normal bacteria (some on the mucus membranes, others from the gut) as a kind of Trojan horse to get themselves inside the body. Once inside, the retroviruses stimulate a specific immunosuppressive protein, and with the immune system’s guard down, start invading cells and getting themselves reproduced.

Understanding how retroviruses operate is an important step in resolving multiple diseases. Some retroviruses carry cancer-causing genes in their RNA; some integrate themselves into cells primed with mutations and tip them into cancer. Other retroviruses can trigger neurological and neurodegenerative disorders.

To understand how retroviruses operate, Golovkina and her team use specialized, inbred mice that are naturally resistant to some retroviral infections. In these animals, the viruses can gain entry into the cell, but can’t get their RNA inserted into the cell’s DNA. That’s because the mouse’s cells produce a substance—an antibody—which coats the outside of the viral RNA packet, keeping its payload isolated from the cell nucleus.

Photo credit: Daniel Beyer/Wikimedia Commons. Translated by Raul654. CC BY-SA 3.0 – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Golovkina’s work with these mice has already provided significant information that could help us fight retroviral infections. She has identified the single locus—the exact place in the genome—with the instructions for making the mouse’s antibody-coating factor… and it turns out that humans have an analogous gene. Her team has also found a receptor in the mouse immune system that detects the retrovirus and signals the body to make the antibody… and it just so happens that humans have an analogous mechanism, known to detect HIV. So the team has found both a potential target for treatment and an avenue for signaling that target.

More important, they’ve found this antiviral system is present and active from the day the mice are born.

Long experience has shown that babies are best vaccinated several weeks or months after birth, when their immune systems are more fully developed. But we also know that AIDS and other retroviruses can be passed from mother to newborn during birth and breastfeeding. Golovinka’s studies of how mice repel viral attacks can help devise inoculation strategies that protect these babies, as well as adults, from HIV and other retroviruses. It may also help address non retroviruses, like hepatitis, that share some similar mechanisms.

While the complexity of the human system sometimes feels overwhelming, discoveries like these and scientists like Golovkina are, step by step, providing the knowledge we need to live happier, healthier lives.

Elise Wachspress is a senior communications strategist for the University of Chicago Medicine & Biological Sciences Development office

Main photo credit: Thomas Splettstoesser/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Jan 15, 2020 | Evolution, Immunology

by Elise Wachspress

After phenomenal increases in lifespans over the past century, longevity in the US has begun to head in the wrong direction. Since 2014, average life expectancy has ticked downward, from a high of 78.9 years to 78.6 last year—placing us 37th among the world’s countries, tied with Albania and more than five years behind long-lived Japan (83.7 years).

The American Academy for Family Medicine cites several causes: the opioid epidemic, increasing suicide rate, and a rise in maternal mortality. Behind these specific threats lurks a shadowy but more endemic source of reduced life expectancy: growing inequality.

As long ago as the first century, the natural philosopher Pliny the Elder recognized a connection between socioeconomic status and lifespan, citing kings, senators, consuls, priests, and performers who lived to a remarkably old age. Some reasons for the perceived disparity seem pretty obvious: lack of food, shelter, hygiene, and medical care have put poor and less educated people at a disadvantage. But the data show that social status also significantly predicts longevity. For instance, despite war and the treacherous travel involved in their diplomatic missions, our first three presidents lived to ages 67, 90, and 83 respectively, when the average US resident could expect to reach only 37. And a survey of the Academy Award nominees shows that those who won the Oscars lived four years longer than those who didn’t.

How does social adversity get inside our skin? One theory is that low social status revs up genes that control the immune response, perhaps preparing lower-status members of a community to fight infections—but at the same time making them more vulnerable to conditions caused or exacerbated by inflammation, like heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and many others.

To investigate how status might influence the immune system, a group of scientists from the US and Canada studied a population of 45 rhesus monkeys, a highly hierarchical species relatively close to us on the evolutionary “tree.” They divided the monkeys into nine groups of five, observed them over a year as rank was established within each group, then re-sorted them into new groups, placing those of similar social rank together—thus forcing an abrupt change in the individual rank of most of the monkeys.

To see how the change in social status affected the animals’ immune states, the researchers took blood samples from each. They found that the lower the social status of each monkey, the stronger was the inflammatory response engaged by their immune system.

The researchers’ clever experimental design also allowed them to see how past social status affected the monkeys’ later immune states. The researchers found that animals at the bottom of the pecking order in the first year of the study still showed immunological traces of past low status, despite their improved social position in their second communities. And though the correlation was weaker, those who enjoyed high rank the first year also suffered immunologically when resorting forced them into a lower social position.

So no matter how each of these primates started in life, being at the bottom of the social ladder was demonstrably detrimental to their immunological state, even with sufficient food, housing, and care.

Research like this is a good example of how the Duchossois Family Institute (DFI), focused on understanding how to maximize health for the greatest number of people, can help us think more deeply and productively about wellness and what it will take for all to thrive.

This work is also an illustration of the approach to training and collaboration central to the organization of the DFI. The lead authors of the paper, Jenny Tung, PhD, and Luis Barreiro, PhD, both did critical postdoctoral training at UChicago early in their still-youthful careers—much like the cross-disciplinary postdocs that will now be supported through the DFI. Though Tung (a 2019 MacArthur Fellow) is now on faculty at Duke University and Barreiro (after an appointment at the University of Montreal) is now a professor at UChicago, they continue to collaborate closely and productively.

And building on that training and collaborative spirit, they are now leading a new generation of graduate and postdoctoral students to uncover how scientific research can improve health for many across the world.

Elise Wachspress is a senior communications strategist for the University of Chicago Medicine & Biological Sciences Development office.